![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE VIENNA PEACE UTOPIA OF 1815 AND THE WORLD OF TRADE

Since we were and are of the opinion, that the current relations between the great powers, and everything that has happened during the last two years, mean that only the most violent revolution – which we see no reason to fear – could cause a major war in Europe, world peace seems on the whole to be better guaranteed than it has been for perhaps a century. This we called the prospect of a golden age. However, even so, many will regard it merely as a dream; Well, in the end such a dream is still worth as much as a dark and empty prophecy.

Friedrich Gentz (Österreichischer Beobachter 5 Dec 1815)1

The preludes: the unification of Europe through economic warfare

Napoleon unified Europe twice. First in a war characterized by unprecedented violence and mass killing, after the French Revolution and the subsequent European conflict about economic global power, and then by the resistance against him from monarchs, princes and nationalist movements, and the establishment of the European Concert in the peace settlement in Vienna.2

These two unifications occurred from two opposite ideological perspectives yet their methods and consequences had much in common. Both aimed at a legal ordering of the continent (and the world beyond Europe), with warfare as a means for final peace, and both aimed at economic unification: the continental system under France versus the maritime world order under Britain.

The approaches to the economic considerations were different. Napoleon’s unification occurred within the framework of economic warfare and a continental blockade which played off the continent under France against the British maritime power. The Vienna restoration of European politics and ordering of the economy after Napoleon unified continental and maritime global commerce and the international distribution of labour for economic growth under the British hegemon. A second unification instrument was a continental power balance of a new kind combined with princely solidarity for the suppression of new revolutions, social violence and claims for democracy. Britain’s control of an open order of global free trade – an openness more imagined than practised – replaced Napoleon’s closed continental unification.

Napoleon’s unification of Europe was based on economic warfare (the continental blockade) about the control of trade. This overlaid an Enlightenment imagery of a peaceful ordering of Europe and the world through a web of industrial and commercial transactions with a military and martial dimension. The second European unification after the French Revolution – the princely reaction to Napoleon between 1813 and 1815 – maintained this dimension, but the centrepiece moved from the French army to the British navy.

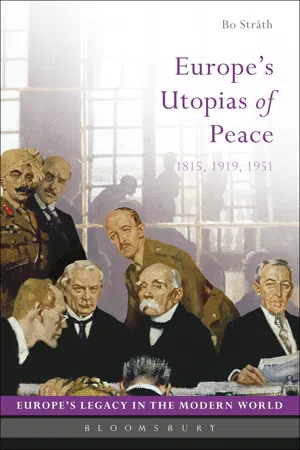

Figure 1: Never Again I. Vienna Congress. Fictive meeting in the Palais am Ballhausplatz with the delegates of the seven signature states and Spain which did not sign but ratified the treaty in 1817. Steelplate engraving 1819 by Jean Godefroy after a painting by Jean Baptiste Isabey, court painter, who followed the French delegation to Vienna where he made portrait drawings of 23 delegates which he put together in the painting.

Standing left to right: the Duke of Wellington, England, Count Lobo da Silveyra, Portugal, Duke de Saldanha de Gama, Portugal, Count von Löwenheim, Sweden, Count Alexis de Noailles, France, Prince Metternich, Austria (in the forefront), Count de Latour du Pin, France, Count Nesselrode, Russia, Duc de Dalberg, France (half standing), Prince Rasoumoffsky, Russia, General Lord Stuart, England, Lord Clancarty, England (leaning over the table), Mr Wacken, England, Mr Gentz, Austria, Baron Wilhelm von Humboldt, Prussia and General Lord Cathcart, England.

Sitting left to right: Prince von Hardenberg, Prussia, de Sousa-Holstein, Count of Palmella, Portugal, Viscount Castlereagh, England (in the centre), Baron von Wessenberg, Austria (at the table), Don Pierre-Gomez Labrador, Spain, Prince de Talleyrand-Perigord, France and Count Stackelberg, Russia.

This chapter will begin with an outline of the historical experiences which provided the backdrop for unification in Vienna through the post-war proclamation of ‘never again’: economic warfare and jealousy of trade, the debate about free trade and protectionism, and about continental protection against British economic power and expectations in benefiting from the yields of that power. The chapter then proceeds to an outline of the peace negotiations and the treaty, and the subsequent conference system. It portrays the Directorate of Europe and its secretary Friedrich Gentz and epitomizes the Vienna peace utopia. It concludes with a comparison of two German thinkers reviewing the peace in 1815 and the Revolutionary Wars through the lens of the Cold War in 1954: Henry Kissinger and Reinhart Koselleck.

The European wars from 1792 onwards were not only about consolidation of the revolution against its enemies: émigrés, frightened princes and others, but also a connected trade-political conflict, important for the consolidation. The conflict was older than the revolution and had its roots in the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) and earlier. Wars about the power over Europe had long engendered conflicts over global economic power. Napoleon and the Revolution gave the old conflict between France and Britain for maritime control a new dimension. The revolutionary ardour and fanaticism in the name of the nation, together with cries for democracy, meant dread and horror of a new kind. However, the commercial dimension of the conflict remained.

The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars began as an attempt to consolidate the revolution through war abroad and became a conflict about commercial power and a global organization of the economy. Napoleon’s continental blockade, the blocus continental, was a large-scale embargo against British trade beginning with the Berlin decree in November 1806. After the defeat at Trafalgar in 1805 Napoleon had little hope of beating the Royal Navy at sea and resorted to economic warfare. Since the 1780s, Britain had been emerging as the manufacturing and industrial centre of Europe. An embargo of its trade would starve Britain of bullion and cause a glut of manufactured and colonial products. Its great debt was a major economic problem which emphasized the country’s vulnerability and increased French expectations of making the blockade more effective. The British Government responded with the Order in Council in November 1807 forbidding French trade with Britain, its Allies or neutrals. The decree instructed the Royal Navy to close French and Allied ports. Napoleon escalated the conflict one month later with the Milan decree.3 He believed that economic collapse would make it possible to invade Britain.

The continental blockade (i.e. the closure of the continental ports for British ships) and the blockade of the French and Allied ports by the British navy involved Europe in a huge political trade conflict. The continental system, as the blockade is also called, followed the general lines of mercantilist trade policy in a combination of a continental self-blockade as against Britain and a British maritime blockade of the continent dominated by the same ideas. The issue at stake behind Napoleon’s campaign against Russia in 1812 was Russia’s participation in the continental blockade. The long-term flaw in Napoleon’s plan was less Russia’s denied participation in the blockade than British naval superiority, which led to many slope-holes to break through the blockade. The control of land borders was often difficult. Smuggling was common and eroded the system.

Historians from Eli Heckscher in the 1920s to Istvan Hont in the 2000s have demonstrated that the continental blockade was inscribed in a long European tradition of commercial rivalry and economic warfare.4 Istvan Hont in Jealousy of Trade (2005) argued that countries see those more economically successful than themselves as threats in a zero-sum game of economic warfare. Hont makes the point that commerce and division of labour explain the differences between the wealth of nations and attempts to emulate the models of the successful evolve into jealousy. Jean-Baptiste Colbert (1619–1683), the French statesman and key figure in the development of mercantilist doctrine and politics, was impressed by the Dutch shipbuilding capacity, for instance, but he failed to emulate the low wages in the Netherlands.

The fact that European debates have long viewed commercially successful countries with envy and suspicion meant, for instance, that ‘perfidious Albion’ took the place of its Dutch rival in terms of trade jealousy. The feelings were promoted by the rise of enemies and neutrals in a number of wars in the wake of the Navigation Act in 1651.

Against the historical backdrop of naval warfare in Europe, which had fostered anti-British resentments, the plans for the isolation of Britain were not very astonishing. Napoleon could draw on earlier proposals in the French administration. In 1747, plans were elaborated in the French Bureau de Commerce to unite France, the Hanseatic Towns (although the Hanseatic League was dead long since), Prussia and the Scandinavian powers with the purpose of crushing the maritime power of Britain.5

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), just a generation before the Revolutionary Wars, provided further material for inspiration, as it had also been a global European war about the control of trade routes and raw materials. The war began in North America before it spread to Europe. The westward expansion of the British colonies located along the Atlantic seaboard clashed with French claims on the Mississippi valley in the late 1740s. In order to stop the expansion of Virginia and Pennsylvania the French attempted to build a line of forts linking Louisiana in the south to the Great Lakes in the north. British efforts to dislodge them led to a military conflict. The war involved most of the great powers of the time and affected Europe, North America, the Caribbean, the West African coast, India and the Philippines. Great Britain, in personal union with Hanover on the one hand and the Bourbons on the French and Spanish thrones on the other, clashed over trade interests among their colonial companies. Through alliance-building and the antagonism between the Hohenzollerns in Prussia and the Habsburgs in Austria the continental powers were drawn into the conflict. The traditional British–Habsburg alliance broke down in the shuffle of coalitions that preceded the war. A British–Prussian camp emerged against an Austro-French–Russian camp.

The colonial part of the Seven Years’ War was mainly a conflict between Britain and France, and, to a lesser extent, Spain.6 The Paris Peace in 1763 stipulated that France must hand over Louisiana to Spain and the rest of New France in North America to Britain with the exception of a couple of small islands. France retrieved the Caribbean islands of Saint Lucia, Guadeloupe and Martinique, commercially lucrative sugar colonies, from Britain. In India, Britain returned all the French trading ports (‘the factories’), under the condition that the fortifications of these settlements were destroyed, which made them worthless as naval bases. France lost its ally in Bengal, and Hyderabad defected to the British. The overall result was that French power in India was brought to an end. The end of the war was not only a colonial land shuffle, it also meant that the French navy was crippled and Britain was in a state of near bankruptcy.

In addition to control of transatlantic trade, the Seven Years’ War was also about commercial power in the Mediterranean where Britain challenged French superiority. Britain sought to secure Menorca as a base from which to interfere with French trade in the Levant. Smyrna, Alexandria and Salonika were major sites of French commercial interest. The French were also active in Syria and on Cyprus. British trade with the Mediterranean grew in the eighteenth century although less rapidly than that with America, Africa and Asia. The growing trade interest in the Mediterranean was hampered by conflicts with France or Spain.7

The Seven Years’ War was, in many respects, a forerunner of the European wars in the wake of the French Revolution a generation later. The French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars are conventionally seen as being constituted by a domestic French conflict that morphed into a large-scale European confrontation about geopolitical and military control of Europe. The global and commercial dimension and the historical continuity of economic warfare between Britain and France over intercontinental trade routes has often been neglected. The Revolutionary Wars began in 1792 as a series of wars with changing coalitions until 1815 with brief interludes of armistices and peace treaties.8 British–French hostility was constant during this martial period of almost a quarter of a century. Like the Seven Years’ War it was a European global conflict which involved the whole world and dealt with control of colonies and trade routes in addition to the political order of Europe after the revolution.9

Gentz vs d’Hauterive and Fichte on the commercial world order

In 1801, Friedrich Gentz (1764–1832), later the influential secretary of the Vienna Congress, portrayed at the end of this chapter, published a book on the situation of Europe and the breakdown of the Westphalian peace order. In 1802 it was translated into English and published under the title On the State of Europe before and after the French Revolution.10 The target of the book was a French pamphlet, De l’état de la France à la fin de l’an VIII published in October 1800 by Comte Alexandre d’Hauterive (1754–1830).11 The French manifesto explained the dissolution of the European state system after 1648 using (a) the expansion of Russia, (b) the growth of Prussia and (c) the global commercial system dominated by Britain. British politics of colonialism and commercialism destroyed the foundations of the Westphalian peace order. The manifesto was directed against those who argued that it was the French Revolution that had destroyed the old order.12

D’Hauterive was a noble who had been patronized in pre-Revolutionary France by one of the leading architects of the foreign policy of the ancien régime, the duc de Choiseul (1719–1785). D’Hauterive first met the abbé de Périgord, the future Talleyrand in the entourage of Choiseul, and through Choiseul he found modest employment in the diplomatic service, in Constantinople and Moldavia. The revolution ruined him but soon he was appointed consul in New York. Unjustified accusations regarding the misappropriation of funds forced him to resign. He found a new living as a smallholding market gardener in the USA. In this humble position he met Talleyrand again, who himself had fled across the Atlantic. D’Hauterive returned to France shortly after Talleyrand in February 1798 and was retained in the diplomatic service. His career was spent in the shadow of Talleyrand, but his role was far from negligible. He drafted 62 of the political and economic treaties made by France and on several occasions acted as interim foreign minister.13

Hauterive’s book was, among others, a response to an earlier pamphlet by Gentz published in 1800 under the title Essai sur l’état actuel de l’administration des finances et de la richesse nationale de la Grande-Bretagne.14 The debate between Gentz and d’Hauterive, defending respectively the politics of Britain and France, was the subject of substantial European attention at a time when the war of the second coalition was about to change to the peace in Amiens. Gentz had begun to receive money from the British Government shortly before he wrote his reply.15 The English translation of Gentz’s reply went through six editions.

This public literary feud dealt with a power balance, but less with a conventional military balance than commercial equilibrium. D’Hauterive refused to see the revolution as the cause of the European chaos, arguing that the European equilibrium established in Westphalia in 1648 had been destroyed by the British commercial hegemony and maritime power. The Seven Years’ War had been a crucial milestone in the erosion of the 1648 order. A new equilibrium could only be re-established at a global level. Britain’s commercial power had to be confronted. Only the British government realized that there was a connection between maritime and continental trade and between national trade and political power. Britain’s aim was to provoke unrest in Europe in order to increase its control of global trade, therefore it had to be subordinated in a système fédératif of all states. Since the scope of the système commercial had spread out beyond Europe since the eighteenth century, recreating the equilibrium was also a task on a global scale. In light of the vast expansion of English colonial and trade power, the new balance must include the transcontinental areas. The new balance which d’Hauterive outlined meant the global containment of Britain.16 The outline envisaged Napoleon’s continental system.

Gentz traced Europe’s woes to the revolution, as opposed to ...