![]()

Part One

Teacher Education and CALL

![]()

1

Learning for the Long Haul: Developing Perceptions of Learning Affordances in CALL Teachers

Karen Haines

1 Introduction

1.1 Nature and scope of investigation

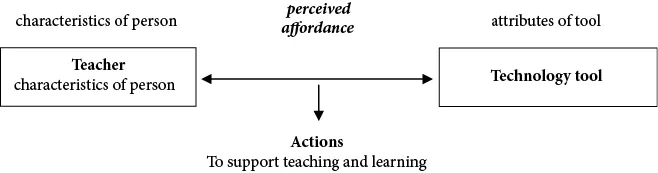

In-service teachers need to identify the affordances that a new tool offers for language learning in order to make decisions about which technologies they will choose to support their teaching practice (Chapelle 2006; Chapelle and Jamieson 2008). The term affordance was originally coined by the perceptual psychologist Gibson (1979) to denote action possibilities that exist between a tool in the environment and an organism that perceives the tool in relation to its own capabilities. Over the last thirty years, the concept of affordance has become prevalent in educational technology, particularly in relation to individual tools. In spite of discussions as to the appropriacy of the concept of affordance in educational technology (Boyle and Cook 2004; Conole and Dyke 2004a, b; Oliver 2005), affordance, as a means of describing how we see potential and interact with our environment, has survived and generally been enriched by its adoption across fields. In this study, the term affordance is defined as the potential that teachers perceive in a particular technology tool that will support learning and teaching activities in their educational contexts. The attributes of the tool and the characteristics of the teacher contribute to these perceived affordances.

Figure 1.1 Extended definition of affordance.

1.2 Investigation of affordances in CALL

In the field of CALL, studies of affordance frequently focus on how students themselves perceive affordances in specific tools such as multi-player games (Rama et al. 2012), speech recognition (Liaw 2014) or asynchronous voice recording (McNeil 2014). However, fewer studies investigate teachers’ perceptions of technological affordances, although theoretical models identify the importance of acknowledging the possibilities for pedagogy inherent in technology (Guichon and Hauck 2011; Hampel and Stickler 2005; Hubbard and Levy 2006).

Being able to perceive affordance in tools is integral to developing the ‘techno-pedagogical competence’ that Guichon and Hauck (2011, p. 191) advocate, but such perceptions develop over time and are specific to individual teachers and their situated contexts (Hampel and Stickler 2012). Tochon and Black (2007, p. 317) analysed the e-portfolios of preschool teachers and found that they clearly tended to ‘subordinate technology use to pedagogy’, identifying affordances that served educational purposes. While general typologies of affordance have been identified for technology use in learning (e.g. Conole and Dyke 2004b), the kinds of affordance that language teachers perceive in technology have not been specified. This study sought to identify the specific types of affordance that in-service language teachers perceive in new CMC tools over time. The research questions that provided a focus for the study described in this chapter therefore were as follows:

- What affordances do teachers see in their use of CMC tools for teaching and learning?

- Do teachers see similar affordances across different CMC tools?

In the face of the rapid development of technology, teachers can be overwhelmed by the need to be continually be aware of the potential that new tools or environments might allow for interaction that could support better learning and teaching. Adopting every new tool that emerges is clearly unsustainable practice for teachers and their students. To develop an awareness of the kinds of affordances that other teachers see in technology, and not to be afraid to recycle principles of language learning and teaching in relation to new tools are crucial aspects of sustainable teacher development.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

This research was based on interviews conducted with sixteen tertiary language teachers in five different institutions in Australia and New Zealand. Four participants taught English in pre-university courses, while the remainder were foreign language teachers working in universities, teaching mainly European languages, with one teacher of Chinese. Snowball sampling was used for selection, and recommendations came from heads of department, with the only parameter being that teachers were recent users of technology in their teaching. Only two participants were male, and all except one teacher were over forty years old. All teachers had more than fifteen years of language teaching experience, and eleven of the sixteen participants had used technology as part of their teaching for more than five years.

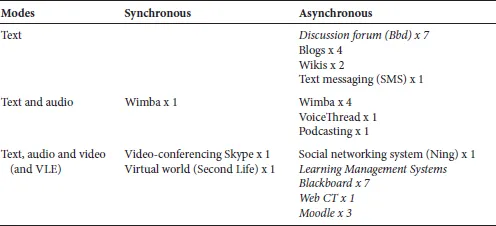

Table 1.1 Tools employed by different teachers in the study

Teachers in the study used a variety of different CMC tools as illustrated in Table 1.1. The modes employed for communication included text, audio and video. Only three teachers made use of synchronous communication tools and none of the teachers used ‘chat’ with their students, which would have been a synchronous text tool. Thirteen of the participants alluded to their broader use of institutional learning management systems (in italics in Table 1.1).

Clearly, the broad affordance of CMC tools is for allowing communication, but this study identified the kinds of detailed affordances that teachers saw in the tools they were using for supporting their teaching and learning.

2.2 Data collection and analysis

Each teacher was interviewed on two or three occasions over a fourteen-month period based on availability. Interviews were semi-structured and approximately an hour in length. Teachers were asked to identify a new CMC tool used recently and then to discuss the knowledge they had acquired through using it. Most had been using their ‘new’ tool for one to two years. While teachers focused discussion on a single tool, they made reference to the other tools that they used.

Through inductive analysis of data collected in the first interview, affordance charts were created for each participant in relation to a single tool and respondent feedback sought on these in successive interviews. In addition, new affordances that the teachers had perceived in the tool over time were discussed.

Two participants were chosen to demonstrate the differences as well as the similarities evident in the way that they developed their perceptions of the same tool. Sue and Lizette, not their real names, were both over forty years old, and worked in different institutions, using blogs in their courses. In addition to the interview data, Sue volunteered access to her personal reflective journal, which contributed to a richer perspective of her understanding of affordances.

3 Discussion

A first step to the sixteen participants’ learning about a particular tool was to acquire a general understanding of what the tool did and how it could be used for language learning. As Sue commented, ‘You have to find out what it can do first, and then you can decide if it’s useful in teaching or not. … If you don’t know how it works, you can’t really know how it’s useful or not in teaching.’

We can get a sense of how different teachers perceive tools from Sue and Lizette’s experiences with blogs as described briefly in Sections 3.1 and 3.2. Three broad themes that came from the overall findings are then discussed in Sections 3.3–3.5, with reference to Sue and Lizette’s data to illustrate the themes.

3.1 Sue’s perceptions of affordances in blogs

Sue had been using blogs with her upper intermediate English students for four years in a course that was repeated each semester. The course focused on written skills, and the general affordances that Sue saw in the blog were related to writing, reading and vocabulary (see Appendix A). The initial attraction of blogs for Sue was the chance to have a website that she could use to communicate with her students, and soon after, she began to see opportunities for learning and teaching if students created their own blogs. Having their own blogs meant that students were producing language for a real audience. Reading each other’s blogs gave them purpose for using language, while Sue identified that writing on their blogs gave some of the shyer students an outlet to express their opinions, which they were less likely to do by speaking aloud in class. Sue also enjoyed being able to embed in the blog images and video files relating to pop culture referred to in the textbook.

Sue’s actualization of these affordances centred largely on the noticing that she encouraged her students to do, and on the possibilities that blogs offered for giving feedback on students’ writing. She recognized the affordance of the class blog for her to communicate with students, but appeared to have less interest in students being able to communicate with each other. Time was identified as a constraint in terms of her own ability to respond to the actual content of students’ writing individually online. She was beginning to explore several different screen-casting tools that meant she could give in-depth feedback on the quality of students’ writing. She also found that the class blog was a great medium for her to discuss the processes of writing and model them for students. She used ‘good’ examples of writing from students’ individual blogs as illustrations of structure and language, as well as for demonstrating her own writing process. Colour was used to identify specific features of her writing such as topic sentences or specific verb forms. She observed a shift having occurred over time in her use of blogs – to being less focused on helping her students learn about the technology itself, and more on exploiting it pedagogically. ‘I think the learning has changed more to ... how we can use what the students are producing, to focus on their needs.’

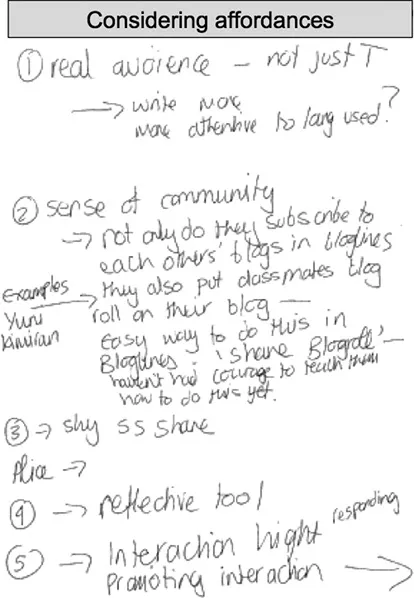

The few affordances that Sue added as new in the second interview included the potential for students to use blogs collaboratively to create text, and also the possibilities that a blog might offer for her own writing. The fact that these perceptions had only begun to emerge after four years of using blogs with multiple cohorts of students highlights the time it takes for teachers to see and begin to actualize the breadth of affordances of a new tool that works in their contexts. The chance to continue to reuse a single tool over time with different groups of students is crucial to sustainable teacher development and gives teachers the opportunity to recognize further affordances, particularly those that are very specific to individuals’ teaching priorities and needs. Sue’s particular preoccupation with writing as a skill and process, rather than for interactive, and possibly more meaning-oriented, purposes was a clear influence on the affordances that she saw in the tool for her immediate use. Students were encouraged to read each other’s blogs, but the affordance that Sue mentioned in regard to this was that reading their peers’ blogs made students more aware of their own errors, which led to self-correction of their personal postings. While she recognized the generalizable learning affordance of blogs for providing an audience and getting feedback from others (see Figure 1.2 for an extract from her reflective journal), this particular communicative aspect did not appear to play a major part in how she used blogs. Sue realized that there was potential for creating community through the ‘blogroll’ (links to other blogs in the sidebar), but reflected that she had not had ‘the courage to teach them how to do this yet’ (Figure 1.2). She did suggest that blogs offered much potential support for learning a language, but stated that she lacked the time and energy to come up with creative tasks that would allow her to exploit all affordances. For teacher development to be sustainable, teachers need space and time to actualize affordances. Sue did not have the resources to make the most of the potential that she could see for her class use of blogs.

Figure 1.2 Affordances of blogs from entry in Sue’s reflective journal.

3.2 Lizette’s perceptions of affordances in blogs

Lizette was excited when she first came across blogs, because she could see real potential in them for her students to receive more French lan...