![]()

1

Introduction

The UK population is ‘ageing rapidly’.1 Government projections indicate that England will experience a 51 per cent increase in those aged over 65 and a 101 per cent increase in those aged over 85 from 2010 to 2030.2 As the ‘baby boom’ generation of the 1960s approaches the state pension age (SPA), the median age of the UK population is projected to rise from 39.7 years in 2010 to 42.2 years by 2035.3

Population ageing is likely to have consequences for industry and government services, including housing, pensions, health and social care, and employment. While legislative and policy measures have been introduced to respond to these challenges, government and society are still regarded as being ‘woefully underprepared’ for demographic change due to a ‘collective failure to address the implications’ of ageing.4

This study critically examines the efficacy of one area of government policy in addressing the ‘ageing challenge’. Using legal doctrinal and empirical mixed methods, I investigate whether age discrimination laws are effectively addressing ageing issues and challenges in the context of employment. Age discrimination laws are seen as having broad potential to achieve instrumental and intrinsic objectives. However, my research demonstrates the substantial limitations of age discrimination laws for fulfilling these aims. Drawing on qualitative expert interviews, statistical analysis and organisational case studies, I illustrate the failure of age discrimination laws to achieve attitudinal change in the UK, and reveal the limited prevalence of proactive measures to support older workers at an organisational level. Integrating doctrinal analysis, comparative analysis of Finnish law, and the Delphi method, I develop an agenda for reform and propose targeted legal and policy changes to address these limitations.

In this chapter, I examine why ageing is likely to be an issue of increasing significance for labour law, and consider the role of age discrimination legislation in addressing the ageing ‘challenge’. I also provide an overview of the book’s structure.

I.Implications of Ageing for Labour Law

Older workers were traditionally a feature of the UK labour market. It was only in 1908 that a state pension was introduced for the ‘very old, the very poor, and the very respectable’ at a level (just) sufficient for survival.5 For most of the UK’s history, older workers have been expected to remain in employment until no longer capable of working, thereafter becoming dependent on family support or (in recent times) the welfare state.

In the 1970s, the growth of early retirement schemes, private pensions and widespread redundancies targeting older workers caused participation rates for older workers to decline significantly.6 By the end of the twentieth century, a third of individuals in the UK aged between 50 and the SPA did not participate in paid employment.7

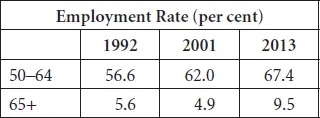

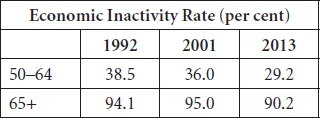

In the last decade, government and employer programmes have focused on counteracting this culture of ‘early exit’ and again increasing employment rates for older workers, both by introducing measures to retain older workers and changing pension entitlements to deter early exit.8 However, early exit remains a significant feature of the UK labour market.9 Tables 1 and 2 show the employment and inactivity rates for those aged over 50 in the UK. While levels of participation for older workers have increased dramatically since 1992,10 the tables still demonstrate that a substantial proportion of older workers are currently not participating in employment. Indeed, over 90 per cent of those over 65 years of age are not involved or seeking to be involved in the labour market.

Table 1: UK Employment Rates for those over 50 (Source: ONS Labour Force Survey)

Table 2: UK Economic Inactivity Rates for those over 50 (Source: ONS Labour Force Survey)

Despite this low level of participation, it appears that older workers are again likely to become a feature of the UK labour market. First, advancements in medical care and improved living conditions mean that individuals are living longer and can reasonably expect substantially more productive, healthy years in their old age.11 Using 2008–10 mortality rates, a man aged 65 can expect to live for another 17.8 years and a woman for another 20.4 years.12 A substantial proportion of these years are likely to be enjoyed in reasonable health:13 in 2011, UK women had an average expectancy of 11.9 healthy life years at age 65 and men had 11.1 years (up from 9.5 and 8.2 respectively in 2001).14 Therefore, individuals are likely to be capable of working for a longer period in old age.

Secondly, there is evidence that a substantial number of individuals will have inadequate income in retirement, meaning they will be financially compelled to continue in employment. In 2008–09, UK government pension benefits15 for a median earner represented only 37 per cent of average UK earnings, one of the lowest wage replacement rates in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).16 The UK is significantly more reliant on private pension provision than other countries.17 However, the ‘truly spectacular flight away’ from defined benefit (so-called ‘final salary’) pension schemes18 in the private sector19 is likely to jeopardise this reliance on private pension provision. At 31 March 2011, only 16 per cent of defined benefit occupational schemes were still open to new members.20 Some employers are now offering their employees defined contribution pension schemes, where the risks of longevity and investment returns are shifted to the individual, rather than employers or the government.21 Other employers had (until recently) ceased to make any provision for their employees’ retirement: the 2009 Employers’ Pension Provision Survey of 2,519 UK organisations showed that employers making any pension provision for their employees had declined from 41 per cent in 2007 to 28 per cent in 2009, with occupational pension schemes being provided in only two per cent of private sector firms (compared with five per cent in 2007).22

The roll-out of pension ‘automatic enrolment’ under the Pensions Act 2008, section 3 from October 2012 may help to extend private pension coverage to many employees. Employers are progressively being required to enrol workers into a workplace pension scheme if they are aged between 22 and the SPA, earn more than a specified minimum wage and work in the UK. However, the level of saving required under the scheme (which is eventually increasing to eight per cent of an employee’s income) is unlikely to address chronic issues of ‘under-saving’ for retirement.23 According to 2012 figures, 10.7 million individuals in Great Britain are likely to have inadequate income in retirement.24 Participation rates for older workers are likely to increase as individuals face stark financial choices and defined benefit pensions become historical relics.

Thirdly, and relatedly, while the low level of public pension provision in the UK has ensured that the state pension system is more sheltered from the effects of an ageing population than other EU countries,25 the UK is still facing a recurrent ‘pensions crisis’.26 As the ‘baby boom’ generation ages, the number of people over the SPA in the UK is expected to increase by 28 per cent, rising from 12.2 million people in 2011 to 15.6 million people by 2035.27 Further, people are living longer, which means they are likely to draw on state pension entitlements for a longer period of time. Indeed, some individuals will spend nearly a third of their life in retirement.28 National Insurance Fund expenditure is projected to increase from around five per cent of GDP in 2008–09 to eight per cent in 2070–71 as a result of the ageing population.29,30

To mediate this pension ‘crisis’, and promote the long-term sustainability of the UK public pension system, the coming years will see a number of increases to the SPA. For women, the SPA will increase from 60 to 65 by 2018.31 For both women and men, the SPA will increase to 66 by 2020 and again to 67 years of age between 2026 and 2028.32 It is anticipated that this latter increase will save the government around £60 billion in today’s prices between 2026–27 and 2035–36.33 The age at which a company or personal pension can be claimed was also increased in 2010 from 50 to 55 years old, encouraging workers with other pension entitlements to remain in employment for longer.

Fourthly, some older workers may actually want to stay in employment into old age. Previous studies have found that many older workers remain in employment as they enjoy work, feel loyalty to the organisation, have a sense of contributing to society or a cause, or feel their work has intrinsic value.34 Therefore, older workers may wish to remain in work for its intrinsic or social value.

Fifthly, the decline in the proportion of ‘prime age workers’ in their 30s and 40s as the population ages may force employers to draw on an older workforce. Labour supply of 20–64 year olds across the EU is predicted to decrease by 24.5 million people between 2010 and 2050.35 While this is unlikely to create a generalised labour shortage, particularly...