![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The willing suspension of disbelief

Although the “willing suspension of disbelief” has been frequently borrowed from Coleridge to address problems in literary theory, such appropriations generally do not seek either to define or to realize literature’s purpose in human life. That, instead, would be the type of inquiry pursued by Socrates outside the walls of Athens in Plato’s Phaedrus, a dialogue that ultimately sees beautiful rhetoric leading to a fulfilling, god-like vision of Beauty itself, of “whole, simple, unchanging, and blessed visions” and insight into “Being, the Being that truly is” (31, 28; 250c, 247d). Rather than fostering fulfillment, the “willing suspension of disbelief” is focused on mitigating two fears, both derived from what Plato called the writer’s art of psychagogia, or the guiding of souls (45, 261a). As Stephen Scully notes, this Greek term summons an image of the artist as necromancer, bearing negative connotations of a Prospero-like figure’s “conjuring up of souls from the underworld” or influencing through “witchcraft or enchantment” (45 n. 106). This fear of the magi-artist, who can overpower an individual’s reason and will in order to undermine or enforce social dictates, has persisted in critical models. So too, however, has another, opposite fear: the dread of a life without any such magical “guidance.” Plato argues that an uninspired soul will be subject to a safe but “slavish economizing” that will lead to roaming futilely and infertilely “for 9,000 years around the earth and beneath it, mindlessly” (39; 256e–257a). In other words, avoiding or banishing literature’s wondrous effects would lead to a life devoid of affect and insight. In Abolition of Man (1943), C. S. Lewis has argued that such guardedness has become so prevalent that the “modern educator” was not needed “to cut down jungles” for the wild youth “but to irrigate deserts” for the barrenly cynical and skeptically disenchanted reader (13–14). These two fears are interrelated as avoiding one seems to result in the other. This chapter begins amid the culture wars of the romantic era with Percy Bysshe Shelley’s debunking of literary power in “Ozymandias” and outlines how this justifiable resistance to the aesthetic informs the “critical vantage” of Jerome McGann’s early New Historicist criticism and Terry Eagleton’s political criticism. Yet both these critics also recognize that this disenchanting methodology leads to the desert and both seek “guidance” from literature nevertheless. The recent return to the “willing suspension of disbelief” by New Historicist critics such as Catherine Gallagher seems to represent an attempted middle way that charts a course between the feared results from both aesthetic absorption under the wizard and the critical vantage of the desert. Ultimately, however, I will argue that even in Gallagher’s compelling construal, the “willing suspension of disbelief” inadequately addresses this fundamental dilemma in literary theory and cannot ultimately lead readers to the human goods for which literature provides hope.

Into the desert: The critical vantage and the Wizard of Ozymandias

When Prospero dissolves his masque in The Tempest, he abruptly shuts down a captivating literary moment and subsequently steps back to offer an apologetic, explanatory theory about the illusory nature of dramatic art. While these reflections are far-reaching, speculating about the reality of the world and life itself, Shakespeare’s closing exploration of aesthetic illusion may not be the most radical example of a work of great literary power voicing concern about literature’s great power. While Shakespeare wrote in the wake of the English Reformation, the romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley promoted revolutionary reform in his own corrupt, undemocratic nineteenth-century England in the turbulent times following the French Revolution.1 Against his message of hopeful change stood a reactionary power structure, which was instituted by George III and later maintained by the Prince Regent in fear of Revolutionary chaos and Napoleonic might. Even after Napoleon fell at Waterloo in 1815, government officials, such as Lord Chancellor Eldon, Viscount Castlereagh, and Viscount Sidmouth (the foreign and home secretaries respectively under the intransigent prime minister Lord Liverpool), resisted any moves toward reforming parliament, extending voting rights, or emancipating those outside the Anglican establishment from long-standing forms of religious discrimination. Shelley accordingly portrayed them as representatives of the deeper human ills of murder, hypocrisy, and fraud in his 1819 poem “The Mask of Anarchy,” which reacted to the government’s deployment of the military strength it had shown under the Duke of Wellington at Waterloo against peaceful protesters at the so-called Peterloo Massacre in Manchester. Leigh Hunt, who had published his journal The Examiner from a jail cell following a politically motivated conviction for libel, balked at printing “The Mask of Anarchy,” demonstrating how charged the written word had become in what Jeffrey N. Cox has called the romantic “culture wars” (Poetry and Politics 13).

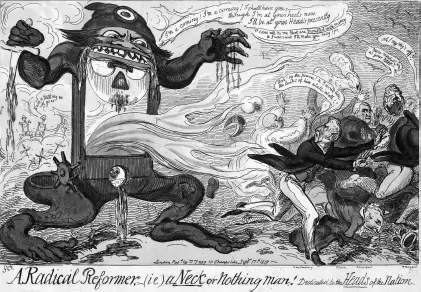

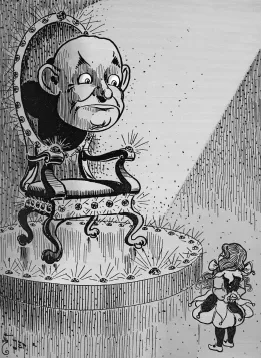

In this ideological fray, the conservative press contended that even the most reasonable and limited reforms should be suppressed, lest they occasion a British version of the French Terror. Kevin Gilmartin has described this intense, monitory reaction to the Revolution as an “ideological mobilization” that had “profound consequences for literature and the arts as well as the press and public opinion” (“Counter-Revolutionary Culture” 129). The amplified anxiety within the counter-revolutionary campaign received satiric representation in George Cruikshank’s “A Radical Reformer, i.e. A Neck or Nothing Man!” (Figure 1.1), which animated a monstrous French guillotine rampaging through English streets after “the Heads of the Nation,” namely Eldon, Castlereagh, an unnamed bishop, and the Prince Regent who escapes from the frame and the flame. It would be easy to mistake this elaborately gruesome work as itself a reactionary image that warns Britons against the bloody consequences of flirting with French Republicanism. The guillotine’s “I’m a coming! I’m a coming” hardly seems a hopeful democratic anthem. As Robert L. Patten argues in George Cruikshank’s Life, Times, and Art (1992), however, Cruikshank’s images “often point overtly to one reading while conveying another” (xiii). Although Cruikshank was no clear political partisan, he was in these years “involved in popular Radical causes and associated with printers, publishers, and a Radical underworld” and was waging “propaganda wars” for his friend and “political mentor,” the radical publisher William Hone (Patten 126, 121, 151). In 1820, George IV would even offer to buy Cruikshank’s silence, an offer, like that made to Hunt in 1812, did little to silence his critiques.2 Given Cruikshank’s commitment to some form of radical reform, how should this complex cartoon of a “radical reformer” be read? On one account, Cruikshank could be representing popular violence as a bargaining chip, a veiled threat: promote reforms benefitting England’s oppressed or else England’s oppressed will, à la française, head for England’s “Heads presently.” Even Shelley’s call to nonviolent civil disobedience in “Mask of Anarchy” subtly invokes this monition by calling on the “many” to “rise like lions after slumber” against the “few,” lines recently invoked by the Occupy movement on behalf of the 99 percent. Patten has indeed located the thematic warning that “government oppression could lead to revolution” in Cruikshank’s work of this period (157).3 There does, however, seem to be yet another level, a metalevel, of cultural commentary in the graphic. Cruikshank’s image of the sanscullote executioner goes well beyond suggestion to the point of hyperbole. Its size dominates the picture’s frame. The sanguinary red of its liberty cap is only outdone by angry red flames and ubiquitous drips of blood. Its presence sends everything into indistinct confusion, smearing out any sense of place, time, order, propriety, community, or context in the picture. Nothing besides remains but the self-preserving panic of the fleeing elite and the frightful fiend they imagine to be close behind. Cruikshank seems to have raised the French monster as an ironic representation of the inflated fear and dread that circulated throughout British counter-revolutionary culture. Cruikshank gives life to the looming Gallic monster, but this “guillotine of the mind” exposes the ruling class’s narrowed imaginary of overwrought gore and chaos. Revealing this extremism thus takes the life out of counter-revolutionary propaganda. The Guillotine rises as a monument of reactionary mobilization, but likewise shows why it warrants circumspection like one of the Wizard of Oz’s initially fierce but ultimately phony facades, particularly the “enormous Head” that had left Dorothy full of “wonder and fear,” though with more courage than Cruikshank granted to the English elite (127; Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.1 George Cruikshank, “A Radical Reformer,—(i.e.) A Neck or Nothing Man! Dedicated to the Heads of the Nation.” London: Thomas Tegg, 1819. © Trustees of the British Museum.

This undercutting of monuments is a consistent trope within Cruikshank’s work and found focused expression in his treatments of Hyde Park’s enormous naked statue of “Achilles.” After its 1822 installation as a tribute to the Duke of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon, its strategically placed leaf raised a controversy over public decency, but it should also raise the question of why the Greek hero was nude in the first place. In the Illiad, the armor of Achilles gets almost as much attention as his rage. He is without it only at one point—when it has been borrowed by and then stripped from Patroclus. A vengeful Achilles cannot rejoin the battle to reclaim the corpse of his fallen friend while he awaits newly fashioned gear from the gods, so he ascends the ramparts to let the Trojans know of his imminent return:

FIGURE 1.2 W.W. Denslow, “The eyes looked at her thoughtfully.” The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum. Chicago and New York: George M. Hill, 1900. Reproduced courtesy of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania.

. . . and so, thus standing there,

He shouted; and Minerva, to his shout,

Added a dreadful cry; and there arose

Among the Trojans an unspeakable tumult.. . .

Thrice o’er the trench divine Achilles shouted;

And thrice the Trojans and their great allies

Rolled back; and twelve of all their noblest men

Then perished, crushed by their own arms and chariots. (8–9)4

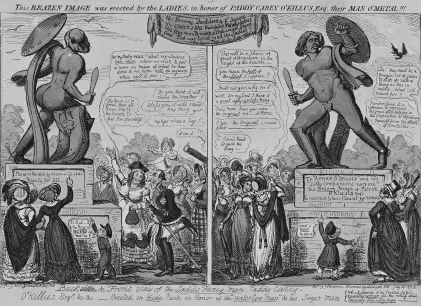

This is psychological warfare at its most potent, and the passage captures Achilles in his most monumental and most Ozymandian moment. Hyde Park’s elevated, naked Achilles would thus be a warning symbol of just retribution and incontestable power. Yet Cruikshank lampoons the classical presumptions and undercuts the martial nobility of the massive statement in stone. In his treatment, the monument is another “monstrosity” akin to the preening ornamentalism of the Regency patrician class, who step obliviously in the shadow of their leader (Figure 1.3). Another 1822 cartoon, “Backside & front view of the Ladies Fancy Man, Paddy Carey O’Killus,” is almost too replete to summarize (Figure 1.4). The real Wellington stands below in impotent admiration, while a flurry of jokes, questions, and ejaculations from titillated women and confused children distracts from any intended sense of might, majesty, shock, or awe. Whether through blatant ridicule or ironic reversal, Cruikshank’s works share the common project of neutralizing the aesthetic power and ideological sway of counter-revolutionary monument-making.5

FIGURE 1.3 George Cruikshank, “Monstrosities of 1822.” Cruikshankiana. London: McLean, 1835. Reproduced courtesy of Bryn Mawr College Library, Special Collections.

For an oppositional reformist, this iconoclastic approach was urgent as the British nineteenth century developed into an age of monumentalization, primarily for lauding Admiral Horatio Nelson or Wellington, those national heroes who turned back Napoleon in 1805 and 1815. While London’s Trafalgar Square with its towering Nelson’s column and the immortalization of Wellington with a triumphal arch were realized in the Victorian period, others popped up immediately in the romantic.6 Completed in 1806, a Glasgow column in honor of Nelson predated a similar construction near Portsmouth by one year, his Dublin pillar by two. Throughout the nation, funereal tributes to all of the captains of Trafalgar radiated out from Nelson’s grand tomb in St Paul’s Cathedral. The call for a national monument commemorating Waterloo emerged instantly, though its completion would be delayed greatly. The first monument to Wellington himself sprang up in Somerset in 1817, another Orientalist obelisk. The Examiner reported on this cultural development that explicitly brought together art and politics. In 1811, the journal lamented the lachrymose tribute paid to Nelson at Guildhall, eschewing a review because the monument was “so defective, that the reader’s time must not be wasted in reading what would consist altogether of censure” (“New Monument” 284). This preventative critical technique is significant as it does not allow the reader an encounter with the shape, size, and effects of the monument, not even one that would be second-hand and censorious. Nevertheless more monuments were to come and, after 1815, the government’s bungling of the commissioning of the Waterloo national monument was a recurrent theme for the journal.7 For The Examiner, the disconnect between the “men in public life” and the nation’s “genius and ingenuity” seemed to speak to deeper problematic issues “in the present situation of the country” (“To the Editor” 108).

FIGURE 1.4 George Cruikshank, “Backside & front view of the Ladies Fancy Man, Paddy Carey O’Killus.” London, 1822. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Perhaps more significantly, The Examiner honed in on the literary parallel to this momumentalizing trend. In 1816, Hunt aggressively reviewed the Waterloo sonnets William Wordsworth published in the Champion. He singled out the sonnet “Inscription for a National monument, in Commemoration of the Battle of Waterloo” with the razing comment that it had “nothing particular in it as to poetry” (58). Here again, Hunt denies the aesthetic access that even a negative review would provide. This preclusion, which would shield his readers from the work’s intended wonderment, seems his most crucial tactic as a critic. Wordsworth was not alone in attempting to do in print what others were trying in stone. Robert Southey erected his two-volume Life of Nelson in 1813, the year he received the laureate from the Prince Regent. In 1816, he stood before readers a Poet’s Pilgrimage to Waterloo, a massive work that begins as a Spenserian travelogue only to open up into an imperial prophecy that celebrates Wellington’s pivotal role in salvation history. Its eschatological message opposes reform with a monumental poetic tribute to Wellington and his warriors that echoes the Ozymandian claim to a “glory that shall last from age to age!” (4.25). Southey’s Life of Nelson explicitly apotheosizes its anti-Napoleonic hero in order to save the age. He quotes the parliamentarian, poet, and journalist George Canning’s epitaphic “Ulm and Trafalgar” as an epigraph to show that not even the limits of mortality could deter Nelson’s great task:

Bursting thro’ the gloom

With radiant glory from thy trophied tomb,

The sacred splendour of thy deathless name

Shall grace and guard thy Country’s martial fame.

Far-seen shall blaze the unextinguish’d ray

A mighty beacon, lighting Glory’s way;

With living lustre this proud Land adorn,

And shine and save, thro’ ages yet unborn. (iii)

Remembering the memorial tomb allows the military hero’s spirit to hold sway in the present and future. The summoning continues as an imposing engraving of Nelson’s visage accompanies Canning’s words (Figure 1.5). The leader once again seems to be present, glaring beyond the confines of the book with a judging stare, ready to command again. These monuments all attempt to assert looming control over current politics by revitalizing the honorable dead or by elevating a living hero into an unquestionable pantheon.

FIGURE 1.5 Robert Southey, The Life of Nelson. Vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1813. Reproduced courtesy of Princeton University Library.

“Ozymandias,” one of Shelley’s most famous sonnets, continued the project of Hunt and Cruikshank and likewise sought to defuse the anxious pressures and fear-mongering monuments that pervaded what Gilmartin calls romantic-era “print culture” and “public expression” around the time of Pe...