![]()

1

IN THE POWER OF GOD ALONE?

MARTIN LUTHER AND THE THEOLOGY OF THE REFORMATION

For a variety of reasons, some more compelling than others, the theological debates and controversies that defined and shaped the Reformation have receded from our view in recent years. There are, of course, some honourable exceptions to this assertion, but the same emphasis upon the culture of reform, the reception of religious change and the long-term impact of the Reformation upon belief that has made recent scholarship so exciting has also run the risk that the theologies of reform become increasingly marginalized. The subtle but important shift from the history of the Church to the history of religion in the final quarter of the twentieth century has diverted attention away from the doctrines and apologetics of the intellectual and theological elite, towards what we might loosely term ‘popular religion’, or the faith of ‘simple folk’.1 These were not the passive recipients of new ideas, accepting unquestioningly the sermons and polemic that defined and explained justification by faith, sola scriptura, or any of the other guiding principles of early evangelicalism. Rather, through the prism presented by histories of early modern culture and society, the laity and local clergy emerged as active agents, participating in, and remodelling, a new religious understanding. Where older, traditional narratives depicted the crystallization of Reformation theology in the minds and works of the ‘great men’ of the nascent Protestant churches, the origins of these ideas seemed to matter less than their impact.

It is quite right that the history of the Reformation should be more than the history of academic theology, but the process of understanding the means by which theological and pastoral change was adopted and adapted in the parishes, in lay religion and in the hearts and minds of the faithful still needs to start with a sense of where these ‘new’ beliefs came from. Of course the narrative of the evolution of belief is never simple. The discussion of Reformation theology (or perhaps more accurately, theologies) over the last few decades has become increasingly anchored in the faith and practice of the later medieval Church: the history of the Reformation begins not in 1517, but some 200 years before.2 A growing interest in the ideas that underpinned the collapse of Christian unity in the first half of the sixteenth century has been a natural concomitant of the burgeoning interest in the origins and impact of reform. Study of the reformation in the parishes, or of the operation of religious belief in the social and cultural sphere, has in many respects served to refocus our attention on the competing theologies that drive this change. The narrative of the Reformation as a history of doctrine or a history of society need not be mutually exclusive, and an intermingling of these strands has greatly enhanced our appreciation of both. Cultural and social histories of religious change have drawn upon analyses of theological debate, while scholars of intellectual dialogue and disputation have rejected any assumption that these ideas were of no concern to a popular culture that was grounded in superstition rather than faith. As the editors of one of the best recent studies of Reformation thought have reminded us, theology may once more be centre-stage in scholarship, but its position is contextual and no longer tethered to the intellectual pillar of historical theologians. Rather, debates over Reformation theology are to be found in works of history and literary studies, cultural and social analyses of the age of reform. Theological principles did not arise in a vacuum, but grew out of the broader environments into which they were planted. The discussion of theology therefore requires a similar willingness on the part of the scholar to reflect upon that context and to seek out the practical impulses that acted as a catalyst or a brake on doctrinal change. Salvation was a practical, rather than abstract, theoretical concern, and the question of how to secure the fate of one’s eternal soul mattered across the broadest demography. The theologians of the Reformation were themselves its pastors and preachers, and our ability to access their ideas and ambitions derives from a reading of the means by which they were communicated: sermons, polemical treatises, letters of support and exhortation.3

THE START OF THE REFORMATION?: 31 OCTOBER 1517

In February 2015, the toy manufacturer Playmobil announced that its figurine of Martin Luther was the fastest-selling model in its range. Within 72 hours of its release, some 34,000 figures of Luther, complete with hat, quill and German Bible, had been sold.4 A spokesman for the company conceded that the popularity of the Luther figurine had come as something of a surprise, attributing the rapid sales, primarily in Germany, to a growing interest in history and the desire of parents to ensure that their children grow up with an understanding of how ‘a totally normal person [who] shared the belief of the majority of the people of the time’ could still speak to a twenty-first-century audience. The mass production and consumption of the Playmobil Luther pays homage to the traditional legend and imagery of the origins of the Reformation. Luther, in this story, articulated his grievances against the Roman Catholic Church by hammering his 95 Theses to the door of the castle church in Wittenberg. This open expression of difference, even defiance, sent ripples across Christendom, presented a new analysis of the relationship between man and God, and rocked the foundations of the institutional Church. The image of Luther, with hammer in hand, emerged as an icon in its own right, leaving an indelible mark upon the representation of the Reformation in art and print and on screen.

Erwin Iserloh’s assertion in the 1960s that ‘the theses were not posted’ was an act of iconoclasm as bold and as controversial as those of the sixteenth century.5 The legend, Iserloh contended, was the creation of Luther’s companion Philip Melanchthon, although the fictional narrative of the Reformation that the legend invited and incited was cemented by the determination of Luther and his followers to establish a date on which the ‘foundation’ of the Reformation had been laid. The fact that the legend could not withstand scholarly scrutiny, he argued, presented compelling evidence that Luther had not intended to rush headlong into conflict with the Roman Catholic Church, and that the process that we know as ‘the Reformation’ had been initiated ‘quite unintentionally’.6 The origins of Luther’s thought, Iserloh suggested, might be better understood within the context of late medieval nominalism, rather than in the events of October 1517. Iserloh’s assertion that Luther’s reformation was unintentional perhaps echoes the lexicon of Melanchthon’s account of the posting of the 95 Theses on the church door.7 For Melanchthon, this was the ‘beginnings of this controversy, in which Luther, as yet suspecting or dreaming nothing about the future change of rites, was certainly not completely getting rid of indulgences themselves, but only urging moderation’. Yet that failure to appreciate the significance of the event need not be negatively construed. As Michael Mullett has suggested, Luther’s lack of knowledge imputed to the events of 31 October an almost providential purpose. Luther, as the human instrument of God’s purpose, did not yet perceive the divine plan in its entirety. If Luther was the agent rather than the means in this context, then the work of reformation was also enacted through the will of God, not man.8

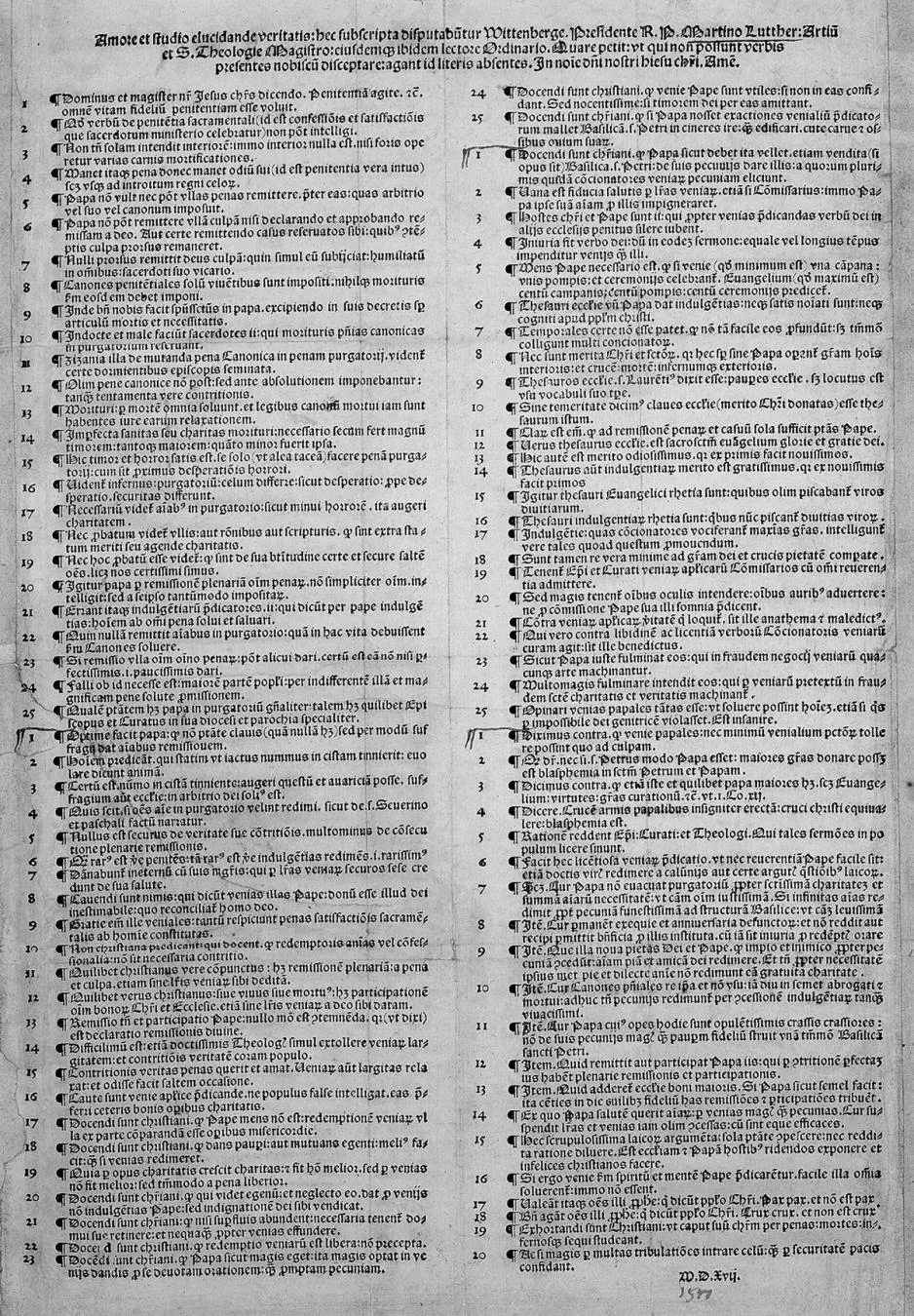

Fig. 4: Martin Luther, 95 Theses, 1517

The reality and symbolism of the nailing of the Theses continues to be energetically debated, but the modelling of 31 October as ‘Reformation Day’ has ensured the continued presence of the story of the 95 Theses in almost every narrative of early German Protestantism. Frederick Wilhelm IV (1795–1861) sought to make good the damage that had been sustained by the Schlosskirche during the Seven Years War and the Napoleonic Wars, arguing that, if nothing else, the door of the church must be restored ‘this door is a monument to Reformation History. Let us renew them in kind, poured in ore, and just as Luther attached his 95 Theses, engrave the Theses on the door in gold.’ In 1858, the bronze Thesenportal were installed at the entrance to the church on Reformation Day.9 In many respects, the veracity of the story matters less than the content and reception of the Theses themselves. Written in Latin, posted on what amounted to a general bulletin board for debates and news, the physical text that Luther published on the church door was undoubtedly less significant than the fact that his ideas spread widely, and immediately, within and beyond the academic community. Martin Luther remains, understandably, the starting-point for the history of the Reformation, although the extent to which either the ‘key man’ or the ‘key moments’ of his life set in train a process that transformed the European understanding of God remains contested. This is not to deny that which was significant, or radical, in Luther’s evolving theology. But rather than assume that the true import of his thought and actions was perceptible from the outset, it is vital to situate Luther’s ideas within the context provided by his life, the social and intellectual context in which he worked, and the response to the first stirrings of reform that did so much to shape the way that the story unfurled.

Fig. 5: A. Savin, Luther’s 95 Theses engraved above the door of All Saints’ Church, Wittenberg

A copy of the Theses was dispatched to Albert, the Archbishop of Mainz, who drew them to the attention of the Pope Leo X, but at this point, there was no formal response. Leo reportedly dismissed the Theses as an ‘argument among monks’, an academic disputation and debate rather than a determined attempt to subvert the foundations of the Church. A formal response came in the bull Exsurge Domine (1520), but by this point the dissemination of Luther’s ideas was more widespread. In 1518, Christoph von Scheurl and a group of Luther’s students from Wittenburg translated the document into German and published it, thus spreading Luther’s ideas among a broader audience. In order to stand as the nominal or figurative start of the Reformation, the Latin manuscript of propositions needed to find its way into the vernacular culture of the time. And if the Theses were not the intentional start of a reformation, neither were they a fully formed description of Luther’s views; criticism of indulgences in the early sixteenth century was neither new, nor unique to Luther, and the key principles that are commonly associated with later Lutheran theology are not yet in the foreground. They contained no outright rejection of papal authority (although there were some strident criticisms of papal conduct), no open statement of schism and no attempt to extrapolate from the specific question of indulgences to the other theological and devotional pillars of the late medieval Church. So what, for Luther, was at stake here, and how did context and concept intertwine in his actions and their outworking?

MARTIN LUTHER

The details of Martin Luther’s life are well mapped in a multitude of biographical studies, historical theologies and discussions of the manifold ways in which Luther has been imagined and reimagined across different chronological, geographical and confessional boundaries.10 Martin Luther was born in Eisleben in 1483, the son of a mine owner, who was encouraged in his youth to pursue a career in law that would be both respectable and financially secure. To this end, in 1501 he enrolled at the University of Erfurt, and seemed set to fulfil his family’s ambition. Decades after the event, Luther described a momentous incident in the summer of 1505, which was to change the course of his life. Caught in a thunderstorm on the road near Erfurt in the principality of Saxony, and fearing for his own survival, Luther invoked the intercession of St Anne, and vowed to become a monk if he was spared. In July, he entered the Augustinian house at Erfurt, in fulfilment of his promise. This was no easy way of life, but Luther dedicated himself fully to its demands, spending time in fasting, prayer, the examination of conscience and confession. As he later commented, ‘If anyone could have earned heaven by the life of a monk, it was I.’ But the pious fulfilment of these obligations did not bring for Luther the comfort and assurance that he sought. Rather, the opposite was true; Luther was to refer to these years as a period of deep spiritual despair in which he ‘lost touch with Christ the Saviour and Comforter, and made of him the jailer and hangman of my poor soul’.

The physical and spiritual sufferings that followed from Luther’s overriding sense of his own weakness and failings took their toll bodily and mentally, but these months of despair also helped to shape Luther’s own understanding of his relationship with God. His confessor, Johannes Staupitz, encouraged Luther to engage with the writings of St Augustine, with which Luther later conceded he had little sympathy at the time.11 But employed at the University of Wittenberg to lecture on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, Luther read and reflected upon On the Spirit and the Letter, On the Trinity and The City of God, and his lectures on the Psalms cited Augustine extensively. It is possible to chart a shift in emphasis and interpretation away from a sense, informed by Biel and Occam, that while man was imperfect, he was certainly not impotent in his own salvation, and capable of loving God. By 1513, in the Lectures on Psalms, Luther was borrowing more extensively from Augustine and the vocabulary of justitia Dei, the justice of God; by 1515 in his lectures on Romans, Augustine had led Luther to a rather different sense of the righteousness of God (Romans 1.17). A month before the posting of the 95 Theses, in his Disputation Against Scholastic Theology, Luther was still more strident in his rejection of any notion that a meritorious human righteousness might be acquired. If it was possible to do, without grace, that which is in oneself (facere quod in se est), to argue that humanity was incapable of fulfilling the law without grace was to transform divine grace into an unbearable burden. And, significantly for what was to follow, two months later in October 1517, Luther reworked the relationship between works, faith and grace to argue that righteous deeds did not make one righteous, but rather having been made righteous by God’s grace, man was capable of, and motivated to do, righteous deeds. Luther, the devout, perhaps over-conscientious, monk, stood on the brink of breaking apart the very principles that guided monastic life.

To see the seeds of the Reformation in the spiritual crisis of one individual is to downplay the importance of the intellectual and cultural climate in which Luther found himself. Luther was certainly not alone in contemplating the essence and purpose of the Christian life. The decades that preceded Luther’s personal discovery of what it meant to be righteous had witnessed calls for reform from inside and outside the institutional Church, some of which had found embodiment in alternative expressions of the religious life, and in more overt rejections of the theology and practice of the late medieval Church. It is no longer acceptable to attribute the ‘success’ of the Reformation simply to the ‘corruption’ of the medieval Church, but the reflection of the Reformation as the ‘harvest of medieval theology’ still provides a useful perspective on the intellectual origins of Luther’s crisis, and its apparent solution. Far from being moribund, the late medieval Church was intellectually vibrant, powerful, self-confident and deeply rooted, despite (or perhaps because of) demands for reform.12 Critics, even heretics, and attempts to suppress them, were not simply a reactionary response, but manifestations of an ever-present reforming spirit within the late medieval Church, and testimony to its institutional vibrancy. Wycliffe, Hus, Erasmus and Luther were all products of this intellectual milieu, as much as the Brethren of Common Life, the Beguines and the Heresy of the Free Spirit were the embodiment of its practical consequences. But if pluralism could mirror vitality, so license ran the risk of exposing vulnerabilities. For Alister McGrath,

[…] an astonishingly broad spectrum of theologies of justification existed in the later medieval period, encompassing practically every option that had not been specifically condemned as heretical by the Council of Carthage. In the absence of any definitive magisterial pronouncement concerning which of these options (or even what range of options) could be considered authentically Catholic, it was left to each theologian to reach his own decision in this matter. A self-perpetuating doctrinal pluralism was thus an inevitability.13

The apparent absence of any magisterial guidance gave rise to a situation in which theological opinions became confused with ‘authorized’ dogma, which eroded the teaching authority of the Church while at the same time permitting a credal pluralism to coexist without repression. A crisis of authority went hand in hand with doctrinal diversity, and provided a stimulating and potentially unsettling context into which Luther’s doubts could plung...