![]()

1

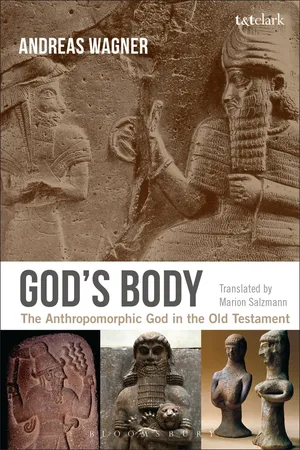

Introduction – An investigation into the external body of God as it can be portrayed pictorially

1.1 God’s external form as the focus of our investigation

No one can talk about God without having an ‘image’ of God in mind. When we talk to or with God, an implicit or explicit concept of God is always present. Many of these concepts claim to be abstract, and consider God as the greatest good, as a force, as an impersonal numinous phenomenon: but in prayer we fall back instinctively on an intimate ‘you’.

Biblical tradition is characterized by the conviction that God encounters mankind as a personal, embodied counterpart. We should not be too quick to transpose this concept into our modern times. We must bear in mind that the biblical concept came into being in a completely different cultural world. Therefore, it must be approached and understood, at least initially, in that context.

Indeed, Old Testament tradition consistently assumes that the concept of the body is the same for humans as it is for God. In Gen. 1, ‘man’ is made in the image of God. Numerous texts reflect the concept of God in human form, painting a ‘verbal picture’ of ‘his’ figure, that is, the body of God. The external image, the (visible/optical) ‘image’ of God, therefore corresponds with the human form, the (visible/optical) ‘image’ of ‘man’. Feelings and actions correspond likewise, as do perception of the organic inner world of God and humans.

This book concentrates on observing God’s external form, which appears in human form anthropomorphically. Connections to other fields such as feelings/emotions/impulses (anthropopathisms1 ), behaviour and action (anthropopragmatisms2 ) and so on will be treated in future works. The methodical approach adopted here thus restricts our observation to the external form. The line of argumentation in this book concentrates on the depiction of the incarnate body in material and verbal pictures. Depictions of the body open up a new understanding of God’s body. As far as I can see, depictions of whole bodies in the material pictorial world of the Ancient Orient or the Old Testament do not include ‘inner organs’. Further, some concepts such as the rûaḥ (spirit) were not, or could not be, depicted in material images. The external bodily form, the figure, therefore appears to be a definable field of research.

This does not mean that we should not be aware of possible connections between the results of our investigation on the external form and the results from investigations on the inner parts of the body (e.g. ræ˝hæm), and other aspects which constitute God and humans. This is also true for the previously mentioned anthropopathisms and anthropopragmatisms. Since a publication cannot hope to encompass all these aspects, I rely on a step-by-step approach and focus solely upon the external form.

1.2 God’s external form between the poles of recent research on depictions and the body

For a new approach to biblical discourse on God in (pictorially conceivable) human form, we must assume a connection between verbal images and material drawings (also called ‘flat images’), statues (sometimes called ‘round images’) and so on. I shall call non-linguistic depictions ‘material images’ to distinguish them from ‘verbal images’. Previous investigations of anthropomorphism have not considered material images sufficiently.

Material images reveal clearly how the external form was ‘seen’ in the Ancient Orient and in Old Testament times. Thus, they are particularly suitable as source material for the concept of the figure and for understanding the (depicted) body. The characteristics of material depictions converge well with those of verbal images.

As we shall see, the way in which a (human) body is understood and portrayed cannot be taken for granted, nor is it the same at all times. Our understanding of the functions of parts of the figure or the body and their portrayal is just as varied today. The understanding of the figure or the body in a given culture is reproduced in their portrayals of figure and body. Further, the understanding of the figure and body in a given culture, in turn, influences their perception of the human figure of God.

One might ask how we can consult material images, in addition to verbal images, for our understanding of ‘pictures’ of God when there are none available (or hardly any3 ) from the Ancient Israelite context and certainly none from the Old Testament. One possibility is to draw on material human depictions from Ancient Israel as well as on material depictions of humans, and of gods, from non-Old Testament contexts, provided by recent research. Both give a good indication of the conception of image and form in the Old Testament, including the ‘image’ of God.

Two impulses are of particular importance for this new approach:

First, we see an ‘orientation towards pictures’ on two accounts, which are in turn interconnected. The last decades of the twentieth century were characterized, according to many new publications, by an ‘iconic turn’. Academic attention has trained on the medium of pictures in many disciplines and subjects, and indeed new disciplines (such as media science, film science, etc.) have emerged.4 The iconic turn correlates with the enormously increased importance of pictures (photos, film, TV, etc.) in the last century. Alongside the general move towards pictures – not independent of it but rather encouraged by it – we find an increased interest in material pictures within Old Testament exegesis in the last third of the twentieth century. This is due, of course, to the increasing availability of source material from the temporal and geographical context of the Old Testament, and the discovery of further pictorial material.5 One can safely conclude that material images have become an important topic in Old Testament studies.

Secondly, new research on the body and concepts of the body provided the decisive impetus for this investigation of the image of God in the Old Testament. The body has become an important topic for the humanities and cultural science in an era where its partial ‘technical reproduction’ has become possible. It has been shown that basic corporeal concepts are subject to cultural and historical change. Attitudes towards the body (friendly or hostile) differ historically and culturally. We have become aware of the connection between parts of the body and communication, the relation between corporeal and non-corporeal parts of humans, the variance of body ideals according to social class, the body as a necessary precondition for recognition and so on. A transdisciplinary field has opened up that has also borne fruit in Old Testament studies.6

Increased interest in depictions and the availability of Ancient Oriental-Old Testament material, as well as new considerations and knowledge of interpreting the body, are crucial keys for understanding the figure of God. To explain more clearly:

a The comprehension of depictions is subject to historical change. If we want to understand Ancient Oriental-Old Testament depictions then we must immerse ourselves in their pictorial world, since it produced an understanding not congruent with ours. We must inquire into the ‘seeing’ which differs from ours.7

It is not easy to discern what constitutes ‘our’ understanding and ‘our’ view of images. Without intending to generalize too much we can say that both the phenomenon of pictures and our reactions to them are varied and complex. Characteristic of our pictorial world is a flood of images and our methods of critique, both of which are influenced by European/Western traditions.

We are all familiar with a flood of images, which greet us on a daily basis. Most of us consume huge quantities every day – TV images, film, photos, advertisements, art and so on. Our experience is that all these pictures, whether they move or not, are initially seen on a flat surface, a screen, a canvas or paper. These two-dimensional materials provide the information we need in order to convert them into three dimensional depictions in our heads. This process is so familiar that we do not realize that we had to learn how to do it.

The critique starts at this point of our normal, unconscious process. Images in the mass media do not demand ‘a complex understanding process’; the television picture ‘relies on a passive attitude on the part of the consumer; it wants to impress our emotions and senses and does not demand sophisticated cognitive processing’, as Bettina Hurrelmann relates when drawing on the work of Neil Postman.8

Blanket rejection of images should be handled with care. Similarly, we should be cautious about polarizing between ‘bad’ or deceptive pictures, which rely on passive consummation, and the ‘good’ heard or written word. Pictures do not threaten human or theological rationality per se. Mindful of the non-pictorial Protestant tradition, we should be wary of such denigrations. Moreover, considering the peculiarities of Ancient Oriental pictorial ‘language’, such blanket denigration makes little sense (see Chapter 4). ‘Images are first and foremost artefacts, which confront the gaze with particular aspects of a concrete or virtual reality. … [T]he viewing of images – in the sense of examination, contemplation, and analysis – is not a facility inherent to the human being. Like speaking, viewing is a culturally mediated competence that needs to be developed and cultivated.’9 If this ‘culturally mediated competence’ or skill is imparted culturally, then it differs according to the culture. This skill is my concern here; learning to understand a culture that is not our own demands a certain amount of effort. We have grown up with a perspective pictorial culture, but in order to understand pictures from Ancient Oriental cultures, we must first agree to the conditions necessary for understanding this very different pictorial culture. Then we will gain a new understanding of the image of God.

b The perception of man and his body varies in different cultures and at various times within one culture. Modern historical anthropology has discovered a new, broad field of research. The understanding of the ‘depiction of the body as an act of communication’ valid for the Ancient Orient and the Old Testament varies substantially from modern understanding of the body.10

The understanding of the body has of course a great influence on anthropomorphic concepts. Each anthropomorphic concept must be understood on the basis of the anthropological context of its respective culture and time. To put it another way, since images of humans change with the times, anthropomorphism is not always the same. If we try to understand Old Testament anthropomorphism with our modern preconceptions of the human form, then misunderstanding is certain. Here, too, we must work at acquiring the knowledge necessary to facilitate understanding.

1.3 Anthropomorphisms, role ascriptions and comparisons

In order to set parameters, I point out here that I will concentrate on anthropomorphisms which concern God’s body directly. Roles ascribed to God will not be taken into account, such as God as the father (2 Sam. 7.14, Deut. 32.6, Isa. 63.16 i.a.), God as the king (Isa. 43.15, Isa. 44.6, Ps. 97.1), God as a war hero (Exod. 15.3), God as judge (Ps. 58.12), God as shepherd (Ps. 23.1), God as midwife (Ps. 22.10–11, Job 10.18) and many others. These could be called anthropomorphisms and verbal images in a wider sense. However, as the short previous overview has shown, they depict God in manifold roles, not specified by gender.

In addition, I shall also not consider explicit comparisons that use a comparative particle, for example comparisons involving ‘as’ or ‘like’ (...