- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Singapore gained independence in 1965, a city-state in a world of nation-states. Yet its long and complex history reaches much farther back. Blending modernity and tradition, ideologies and ethnicities, a peculiar set of factors make Singapore what it is today. In this thematic study of the island nation, Michael D. Barr proposes a new approach to understand this development. From the pre-colonial period through to the modern day, he traces the idea, the politics and the geography of Singapore over five centuries of rich history. In doing so he rejects the official narrative of the so-called 'Singapore Story'. Drawing on in-depth archival work and oral histories, Singapore: A Modern History is a work both for students of the country's history and politics, but also for any reader seeking to engage with this enigmatic and vastly successful nation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Singapore by Michael D. Barr in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Let’s Talk About 1819: Reorienting the National Narrative

Not one stick or stone of present-day Singapore was standing on the morning of Friday, the 29th day of January, 1819. Towards noon of that day two men, the Temenggong Abdul Rahman and Sir Stamford Raffles, with whom the story of the modern city begins, met for the first time in the shade of a cluster of coconut palms on the southern shore of the island.

The opening words of H.F. Pearson’s Singapore: A Popular History (1961)[1]

Singapore has many honours and awards to its name. It routinely tops the World Bank listings for ‘ease of doing business’. As a city it won a 2010 United Nations Habitat Award and as a country it has been recognised as having one of the best health systems in the world. It brims with such confidence in its own international standing that it even gives awards to other countries and other cities – such as its Global City Prize, awarded by the Urban Redevelopment Authority. By any measure it is a remarkable place, especially considering its size. As a country Singapore is tiny (less than 6 million people living on an island at the mouth of the Johor River) and even as a city it is smaller than Sydney, Bangkok, Jakarta and almost any major metropolis you could mention. It is, enigmatically, the largest city-state in the world, beating its nearest rivals, Monaco and the Vatican City, hands down.

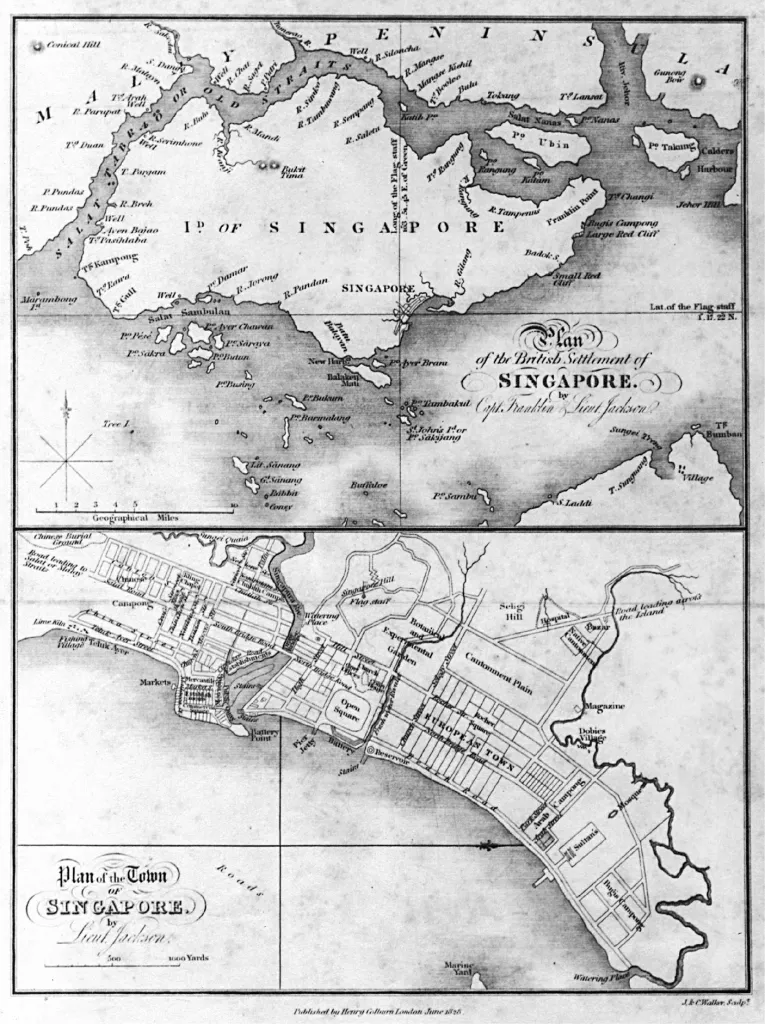

Map 1.1. Plan of the Town of Singapore by Lieutenant Jackson, 1828

In 2018 it was also confirmed for the fifth year in a row as the most expensive place in the world in which to live. This latter point is one of the few honours that is not a matter for boasting by the government and yet being in the league of expensive cities should not be unexpected, since it has been working to a deliberate and substantially successful agenda for many years to become a ‘global city’ like London and New York, one of the characteristics of which is a high cost of living. Yet even on this score, neither the aspiration nor the costly outcome should be taken as being free of nuance. Singapore’s government likes to think that it is different from other global cities in at least one positive respect: that it actively redistributes enough social goods (notably housing, health and education) to ensure that ordinary citizens who are not direct beneficiaries of the wealth generated by the city are at least indirect beneficiaries. Leaving aside the government’s severely limited notions of redistribution and disputes over its success in achieving this goal, it is significant to note that such a neo-Fabian objective is rarely taken on by a city (the experience of London in the 1970s notwithstanding). If this role is undertaken by any level of government it is usually the central, federal or state/regional government, not the municipality.

The government’s social conscience therefore underlines the plain oddity of the extraordinary amount of attention paid to Singapore as a subject of scholarly and public policy study: it is a city-state in an age of nation-states. City-states have enjoyed several historical periods of pre-eminence and in their days have dominated their worlds, but those days are long gone. They disappeared even before the withering of the age of empires roughly a century ago. It is undeniable that the average size of nation-states is getting smaller by the decade (think of the impact of recent additions such as Timor Leste, Macedonia and Kosovo), but this has not translated into a renaissance for city-states. Not a single enduring city-state emerged from the break-up of the Soviet, German, Hapsburg, Japanese, Portuguese or Ottoman empires. The French and British empires gave us just one city-state each (Monaco and Singapore, though Dubai, Abu Dhabi and Hong Kong have survived as quasi-city-states operating with varying degrees of comfort within larger entities). Unprecedented levels of connectivity in both transport and communications and the new importance of service and information as tradable commodities mean that this is a good time for an economy to be based on a great city, and yet every one of the great cities of the modern world remains stubbornly embedded in a nation-state. The twentieth century was very much the century of nationalism, not ‘civic-ism’.

The sobering truth is that it takes a decidedly unusual set of circumstances to create an environment in which the international community will recognise a city as a sovereign state. Such a peculiar set of circumstances accidentally and reluctantly flowed together in 1965 for the Federation of Malaysia to give birth to the Republic of Singapore. With rather more deliberation they flowed together for Mussolini’s Italy and the old Papal States to give birth to the Vatican City in 1929. But the same fortune has failed to smile upon other likely candidates for city-based sovereignty. There is little doubt, for instance, that both Hong Kong and Jerusalem would have been better off as independent statelets with carefully crafted relations with their immediate neighbours, but it was not to be.

A study of Singapore is therefore a study in difference. It may not be sui generis, but it is certainly a rare bird. This particular difference is part of the reason it is so interesting and we can say with a reasonable level of confidence that it is one of the critical factors that explains why it is successful on so many fronts. There is an orthodoxy in Singapore that its small size makes it vulnerable and it has to struggle to prosper – a minnow swimming with the sharks and whales. There can be little doubt that being small creates a distinctive set of vulnerabilities with which a larger entity need not concern itself, and yet short of a direct existential threat there is little reason to think that a city-state like Singapore is more vulnerable to a myriad of formidable challenges than larger countries. Indeed there is much reason to regard the city-state as being an enviable model of an economy/polity. Writing in Foreign Affairs on sovereign risk and regime durability, Nassim Nicholas Taleb and Gregory F. Treverton make this point thus:

City-states both old and new – from Venice to Dubai to Geneva to Singapore – owe their success to their smallness. Those who compare political systems by looking at their character without taking into account their size are thus making an analytical error.[2]

Smallness, they argue, brings with it many strengths, though in itself it is no guarantee of success. Largeness likewise brings with it a baggage-load of its own problems, especially if it is coupled with inflexibility – or a ‘lack of political variability’, to use Taleb and Treverton’s terminology.[3]

Looking Past Raffles and Lee Kuan Yew

I have opened this history of Singapore with this somewhat tangential discourse on the bifurcated nature of Singapore (city and country) as a modest beginning of an antidote to the standard mythology of Singapore, which is premised on the city-state’s vulnerability – primarily due to its size. In this narrative, the future and security of tiny Singapore is guaranteed only by the cleverness and benevolence of the country’s political leaders. The mythology to which I refer finds its zenith in the official, state-constructed narrative of Singapore, which is known as ‘The Singapore Story’[4] and has provided the template for teaching history throughout the island’s schools and junior colleges since the introduction of the National Education programme in 1997.[5] The Singapore Story also utterly dominates the historical narrative in universities, newspapers and other media. It has even been reproduced on the Discovery Channel.[6] Ernest Koh was, if anything, understating the case when he wrote in 2010 that the Singapore Story submerges ‘all forms of remembrance in Singapore, especially among the English-literate majority of the population’.[7] Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng and Tan Tai Yong extend this criticism, calling it a ‘misuse’ of history, but offer some understanding of this misuse by pointing out that this weakness is shared with ‘other national histories’.[8] At its heart the Singapore Story is, to return to the critique offered by Koh, ‘a triumphal narrative of deliverance from political, economic, and social despair … through the ruling regime’s scientific approaches to solving the problems faced by a developing and industrialising society’.[9] T.N. Harper goes further, describing it as a ‘biblical narrative of deliverance’.[10] The enemies from which Singapore was ‘delivered’ are very clearly delineated in this narrative: the chaos of communal discord (most notably Malay ‘ultras’ and Chinese ‘chauvinists’); the pull of extra-national loyalties by ethnic homelands (China; India; Malaysia; Indonesia); communism and leftist subversives, students and unionists; overbearing regional neighbours (Malaysia and Indonesia); and poverty. More recent additions to this litany include Western decadence and liberalism, and religious ‘extremists’ (most notably Catholics and Muslims). The Singapore Story was the product of a state-directed campaign that was launched in the late 1990s, but it built directly on an earlier national(ist) narrative conceived in the 1980s. The earlier iteration underlined explicitly one major feature that is implicit and taken as a given in its successor: that the story of Singapore’s triumphal march to success is essentially a British-colonial and a Chinese-immigrant story. The explicit premise of the national narrative is that before Raffles arrived in 1819 there was, basically, nothing on the island and nothing in the region that need be considered when accounting for Singapore’s success; and without the leadership of Lee Kuan Yew and the followership of industrious, clever and frugal Chinese citizens, Singapore would still be in the Third World.

National(ist) Histories

The mythology of Singapore as a British–Chinese–Lee Kuan Yew success story lies in the perspective generated by the undisputed ‘mother’ of Singaporean history, Mary Turnbull, who denied Singapore’s pre-British past when she opened her seminal A History of Singapore with the memorable words:

Modern Singapore dates from 30 January 1819, when the local chieftain, the Temenggong of Johor, signed a preliminary treaty with Sir Stamford Raffles, agent of the East India Company, permitting the British to set up a trading post.[11]

Turnbull’s contribution to the Singapore national narrative is her lasting achievement, alongside her exhaustive attention to archival material. She stands apart from her contemporaries partly because no other historian matched the way she meticulously and painstakingly mined the colonial archives and then used this material to weave a narrative that was straightforward, readable and informative. Without the archival foundation, it is doubtful that her work would have been so durable that in the second decade of the twenty-first century her books still comprise basic texts for historians researching the colonial period. But this is not the core of her distinctiveness; that is primarily attributable to the fact that she single-handedly, deliberately and successfully created the narrative of Singapore (including colonial Singapore) as a consciously national history. In her national history, Singapore’s story was separate from the history of both Malaya and from Singapore’s pre-colonial past – which until her work triumphed, had been a common and mainstream perspective among historians. Furthermore, she did so as a ten-year project beginning in the 1960s when there was no obvious market for such a national history. At that time the government was actively discouraging the teaching of history, regarding it as irrelevant – and even detrimental – to the task of building a successful Singapore.

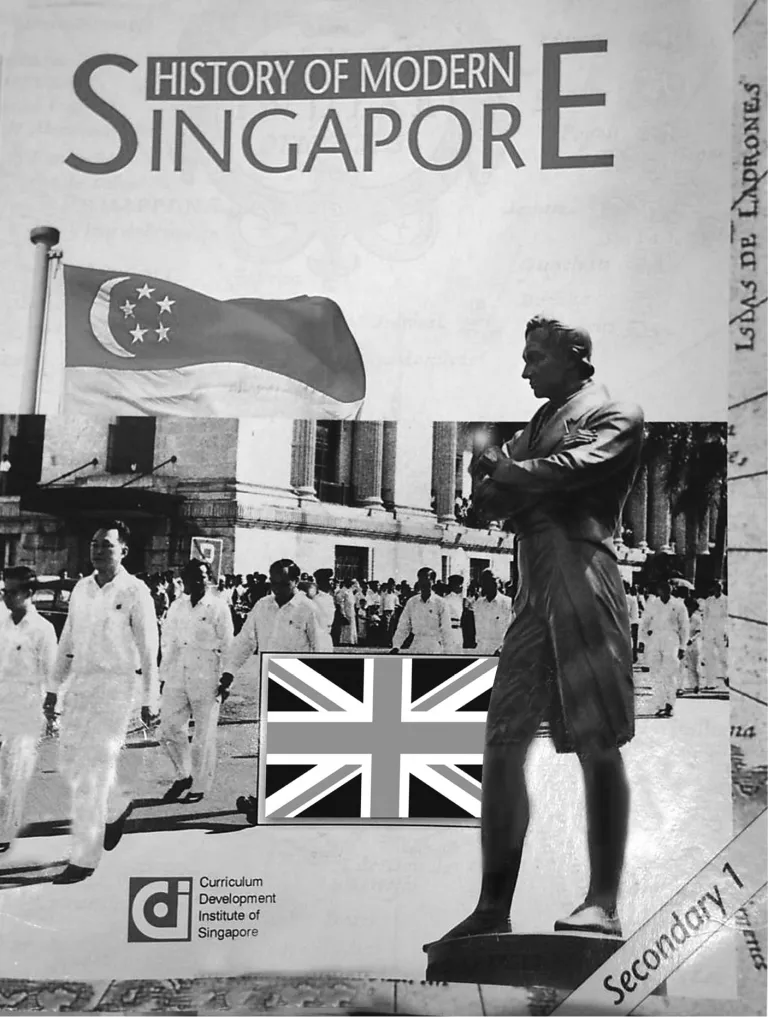

Turnbull’s A History of Singapore was published in 1977. As luck would have it, just a few years after publication – in 1980 – the attitude at the top of government began to change: ministers began ruminating in public about the importance of history as a nation-building tool. Turnbull’s work was promptly embraced by the Ministry of Education and so she provided the template for the teaching of Singapore history in Singaporean schools, junior colleges and the local university. The Turnbull approach was on graphic display in the first generation of History textbooks. Consider the cover of the Secondary One textbook shown in Figure 1.1. It features a statue of Raffles superimposed over a 1959 photo of Lee Kuan Yew and his Cabinet colleagues marching in front of City Hall after being sworn in.[12]

Figure 1.1. Secondary One History textbook, 1984–99

Allowing for some relatively minor changes of inflection, this situation has lasted to today. Turnbull’s history served the nation-building agenda so well precisely because it created a new myth in which the whole of Singapore’s colonial history was presented as the backdrop for its triumphal march to success, delivered by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and his People’s Action Party (PAP) government. This history was uncompromisingly anchored fore and aft by Sir Stamford Raffles and Lee Kuan Yew and it provided the new nation with, as Karl Hack has eloquently expressed it, a ‘genealogy’. Less simply, but more profoundly, Hack described Turnbull’s A History of Singapore as ‘a teleological exercise in endowing a modern “nation-state” with a coherent past that should explain the present’.[13] That it was such an important book for its time was due to its intrinsic strengths: the quality of the research and the groundbreaking analysis. That it has lasted so well beyond its time is due more to its facility to a ruling elite seeking a foundation myth that reinforces its own place in history and politics.

Revisionist History

The Turnbull story, followed by the hegemony of the Singapore Story, planted two pivotal dates in Singapore’s national narrative: 1819 as the foundation of ‘modern Singapore’, and 1965 as the foundation of independent Singapore. The triumph of each of these narratives in turn was absolute in institutional terms and yet they never went completely unchallenged, either by historians or by scholars from other disciplines. Sadly, however, during the 1980s and most of the 1990s none of these critiques came from Singaporeans themselves. This task was left to ‘foreign talent’ because in those decades it would have been a career-killing exercise for a local scholar to have questioned the orthodoxy. Even today, ‘revisionist history’ is a politically charged term wielded by the Establishment as an accusation. In the 2010s, revisionists (labelled by one Establishment scholar as ‘Alternates’)[14] engage in provocative exercises such as seeking evidence before accepting official narratives, especially on matters concerning the ‘riots’, strikes and rounds of detention that have become part of Singapore’s foundational mythology. One of the more contentious exercises a revisionist can engage in is to question the way the official narrative about the 1960s and 1970s carelessly accuses people of being communist or ‘pro-communist’ – the latter being a label that seems to be applied to almost anyone of whom the government disapproved.[15] In the 1970s and 1980s it was worse: you were a revisionist if you merely suggested that Singapore had a history before 1819.

One of the more innovative revisionists of the 1980s was Philippe Regnier, a French scholar whose history opened with a very substantial introduction in which he explored the lines of continuity between Singapore’s pre-colonial past as a regional meeting point and its colonial and subsequent role as a trading city, rather than as a colony or as a nation.[16] Carl Trocki was busy throughout the entire period from the 1970s onwards, producing social histories focused on the Singapore-Johor region that deliberately cast aside and challenged the significance of the colonial (and by implication, the national) borders as the boundary of delineation in local history.[17] James Warren’s bottom-up social histories of the 1980s and 1990s mounted less direct challenges to the national narrative, but were nevertheless notable for their complete disregard for the colonial boundaries, treating Singapore essentially as a city that was part of an East Asian political economy.[18]

Perhaps it should not be surprising, however, that the greatest advances in decentring Singapore’s history from its colonial past and its national present have been made by scholars who are not actually historians of Singapore: John Miksic, an American archaeologist of Southeast Asia for whom Singapore is just one site of interest among many; and Peter Borschberg, a German historian who focuses on Southeast Asia in the period from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century. Miksic’s work on pre-fifteenth-century Singapore was a game-changer in Singapore historiography. The archaeological digs that he ran at Fort Canning from 1984 onwards and which he wrote up for the National Museum confirmed the importance of Singapore as an outpost of the Java-based Majapahit Empire before becoming part of the Malacca Sultanate, which in turn became the Johor-Riau Sultanate.[19] This history was already known, but tended to be sidelined in most accounts. It continued to be mostly ignored even after Miksic’s scholarship started appearing in print because the new material was emerging at exactly the same time that the Turnbull version of the national history was being newly promoted as the country’s official history.

Yet for all its strengths, the work of Miksic and his collaborators has had an unintended consequence: it intensified the focus on Singapore the island, generating a parochial compulsion in official, popular and academic discourse to tie ‘Singaporean’ historical perspectives rigidly to the current national boundaries of the city-state. This was a danger that Wang Gungwu explicitly warned the Ministry of Education about as long ago as 1982, when he wrote that ‘it is a mistake to see Singapore’s history in terms of the physical island’.[20] The mindset against which Prof. Wang was warning, and which subsequently became entrenched in Singapore historiography, is that if it happened across the water, in Johor or Riau, it is someone else’s history, not ‘ours’. Let us admit that a parochial and present-ist focus is to some extent intrinsic to any national history. Such engagement is arguably the legitimate purpose of a national history and I certainly have no illusions that I have been able to escape the island boundary either: not in this book and certainly not in my earlier works, in which the acceptance of Singapore-as-nation (or Singapore-as-colony) was accepted without demure. This is where Peter Borschberg’s contributions are critical, since he is a transnational historian and so is completely free of the national-history genre’s limitations. His contributions are also critical for another reason: he can read Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch archives, which has opened up new vistas of tra...

Table of contents

- Author Biog

- Endorsements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Figures

- Foreword by Carl A. Trocki

- Prologue

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Glossary of Asian-Language Terms

- Timeline

- 1. Let’s Talk About 1819: Reorienting the National Narrative

- 2. The Idea of Singapore

- 3. Singapore Central: The Role of Location in Singapore’s History

- 4. Governance in Premodern Singapore

- 5. Governance in Modern Singapore, 1867–1965

- 6. Governance in Independent Singapore

- 7. The Economy: Singapore, Still at the Centre

- 8. Making Modern Singaporeans: People, Society and Place

- Afterword

- Notes

- Bibliography