![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION: SOCIOLOGY, FOOD AND EATING

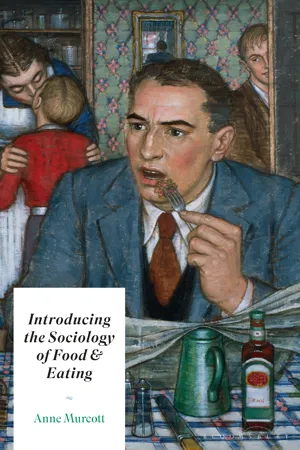

Look at the illustration on the front cover of this book. Part of a painting called ‘Breakfast’ by Alfred Janes, it freezes a moment of a family’s weekday morning in 1950s Britain. It powerfully conveys a sense simultaneously of the social relationships between those portrayed and of each one’s relationships to the production and consumption of the food at home. Turn the book over and look at the thumbnail picture which shows the whole painting. There can be seen that it is the woman – wearing an apron to cover her dress while getting breakfast for everyone else – who is the only adult of the three not at the table. The man in his collar and tie sits there, eating the last of his breakfast, momentarily looking up from the newspaper, almost ready to go out to work. She is the ‘homemaker’ cooking breakfast for everyone; he is the ‘breadwinner’, earning the living for them all. She is kissing goodbye to the youngest boy off to school. The oldest son, adult now, also in collar and tie, sits at the table alongside his father draining his coffee cup – the next generation preparing to follow in his father’s breadwinner footsteps.

The painting has the quality of a still from a film, temporarily suspending movement. Despite the static portrayal of mobility, the very nature of the things (their materiality) is powerfully conveyed – the hasty gulping down the last of the coffee no longer too hot to drink, the smell of the poised forkful of food – coupled with the temporality indicated in the swiftness of the kiss goodbye and the way the middle of the three boys is already half way out of the door. Everything signals a sense of routine, of an ordinary, familiarly rushed weekday morning in which eating, domestic food provisioning and people’s relationships to one another are intimately intertwined – usual, mundane, taken for granted.

Now think of another, very well-known painting, called ‘Freedom from want’ by Norman Rockwell, the twentieth-century American artist. Made in 1942 a few years before Janes’, its title echoes Franklin D Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms. It depicts a middle-aged man in a black suit, collar and tie, standing at the top of the dinner table. His position signals that he is head of the family, the breadwinner. He is beaming at the enormous turkey a smiling woman, with hair as grey as his, is placing on the table in front of him, carving knife and fork alongside ready for him to share it out. Nine others, of three different generations, faces alight with anticipation, are shown seated along each side of the table which is beautifully laid with white cloth, dishes, plates and glasses of water. Once again, the woman is wearing an apron over her dress, signalling that she is responsible for the cooking. She is shown in the very act of serving everyone else.

Social conventions placing men as family breadwinners and women as the homemakers/cooks may (or may not) have changed in the US, Britain and elsewhere since the 1950s. But whatever the prevailing conventions of a particular historical period or a certain region might be, what people eat, what the food signifies and who is expected to undertake the provisioning, are intricately tied in to the way society is organized – often represented in paintings, photographs or fiction. It is these types of social arrangements, social institutions, symbolic significances and the associated materialities that Introducing the Sociology of Food and Eating addresses. All these and more are to come, but for now, ‘to begin at the beginning’.1

Background basics

Food is a fundamental requirement of life. As a result, searching for something to eat is a basic human preoccupation. For most of human history that search has taken place in the shadow of famine and starvation with the threat of hunger a normal feature of daily life. An individual cannot survive much beyond three weeks without food – and only three days without any water. But a whole society is shaken if too many of its population has to go without food. Rising prices, low wages or empty shelves in grocery stores risk civil disorder; hunger goads people to take to the streets. In 1916, ‘housewives’ on Manhattan’s Lower East Side riot in protest against high food prices (Turner 2014). In nineteenth-century England soup kitchens repeatedly reappear to dampen down civil unrest whenever economic depression and high unemployment threaten ‘to disturb the social fabric’ (Burnett 2014: 31). A 2011 paper from researchers at the New England Complex Systems Institute shows that violent protests in both North Africa and the Middle East that year (and riots in 2008) coincide with high peaks in global food prices.2 And as recently as January 2018, Reuters reports widespread looting and violence in Venezuelan towns and cities in the face of ‘runaway inflation’, adding that shopkeepers are defending their premises ‘with sticks, knives, machetes, and firearms’.3

Only for about a century have even less well-off people, especially those in wealthy and more industrialized nations, been able to assume an easily accessible super-abundance of foodstuffs – a new normality for them. It means that it is extremely unlikely that either anyone involved in the production of this book or any of its readers have known hunger – not the hunger anticipating supper after a full day’s revising for exams, or the appetite worked up after a long hike in the countryside, but real hunger that gnaws at the guts, last thing at night, still there first thing in the morning, day after day after day. Perhaps family stories of real hunger are still current. Some reading this book, living in, say, Boston, Massachusetts, may be descended from an Irish arrival who in the years between 1846–1850 flees the potato famine. Fabled as land of abundant food, America acts as a magnet for nineteenth-century migrants where ‘they would not be stalked by hunger as in the old country’ (Turner 2014: 11). Another reader might be descended from someone, perhaps in Seattle, who knows of, if not took part in, the Hunger Marches of the Great Depression of the early 1930s. Other readers, perhaps living somewhere in Europe, may be descendants of people who survived the starvation of the 1944–1945. ‘Hunger Winter’ during the German occupation of The Netherlands.4 More recently, survivors of the 1959–1961 Great Famine in China when millions starved to death, contribute to a study documenting that terrible experience (Xun 2012), while, today, right now, there may be still other readers who have moved elsewhere to live, leaving behind relatives enduring shortages, struggling to find food in war-torn areas of the Middle East or Africa or family acquaintances reduced to dependence on food aid in refugee camps. The shadow of hunger is not lifted everywhere, or for all time.

Newer trends

What is much more recent is that hunger co-exists with that new normality of full supermarket shelves in rich countries – and for the wealthier in poor countries – where being able to find more than enough food can, unthinkingly, be taken for granted. An indicator of this is that the wealthier and more industrialized a nation, the smaller the percentage of household income is spent on food. The smallest percentage is in the US, the largest in Nigeria. On average the amount spent on food in the US is twice that spent in Nigeria. As significant, are the great within-country differences in both rich and poor nations, e.g. for the US ‘over the past 25 years, the poorest 20% of households … spent between 28.8% and 42.6% on food, compared with 6.5% to 9.2% spent by the wealthiest 20% of households’.5 Moreover, this relation is dynamic as illustrated by the nineteenth-century economist Ernst Engel’s proposal: the proportion of income spent on food declines as income rises. It means that, worldwide, plenty and want now stand in a novel relation to one another, historically speaking.

In the midst of plenty there appears to be a recent twist to the perennial human need to get something to eat. In rich countries, journalists, writers and commentators seem fond of saying that ‘we have become obsessed by food’. They describe people being preoccupied by what they eat, whether it is becoming increasingly anxious, citing the increasing numbers of people reporting food allergies, some who worry about another food scare, others concerned about contaminants or additives in food, and those following weight-reducing diets.6

Journalists too point to their own, extensive mass-media coverage of food-related topics: an obesity ‘epidemic’; McDonald’s opening new branches round the world; an outbreak of norovirus responsible for closing a chain of Mexican restaurants; restaurant owners taking the tips diners leave for the waiters; foraging recipes from Finland; the promotion of ‘7-a-day’ (official Australian government advice about the daily number of portions of fruit and vegetables to be eaten for good health, six in Denmark, five in the UK); the spread of food banks in rich countries as far apart as New Zealand, Germany and the US; predictions of food fashions for the forthcoming year including coconut flour, cactus water and the ‘veggan’ diet (vegan with eggs); the headline ‘15 Dead, 5 Hurt in Stampede for Food Aid in Morocco’ – readers can probably add many more to this already long list.

Starting to think sociologically

This book’s point of departure, chapter by chapter, is a selection of rich countries’ ‘obsessions’ to introduce what sociologists have to say about food, society and the perennial human preoccupation with getting something to eat. In it, sociological thinking about food and eating in society is presented as an alternative to and different from such conventional wisdoms on these matters. For present purposes, conventional wisdoms are taken to mean widely held, rather general beliefs – those statements and occasional puzzlements people express when seeking to make sense of things they know, read about or talk over with one another during their daily lives. They take the form of statements of a kind sometimes described as received wisdom, common sense views, assumptions or explanations. These are often plausible, widespread as well as familiar – and can be found incorporated into mass-media discussions of food and eating, newspapers, magazine, online and elsewhere (e.g. at dietitians’ conferences, among marketers developing a new advertising campaign) right through to the companionable chatter between friends in a café. By contrast, one of the defining characteristics of any science is its dedication to adding to the sum total of knowledge that is relevant no matter where or when. In sociology, this requires minor intellectual gymnastics, for researchers obviously live in a segment of the world to which such ordinary language belongs, at the same time as standing apart to investigate that world as dispassionately as can be managed. So, one of this book’s aims is to encourage the scepticism integral to any academic discipline that accepts nothing at face value.

Thorough understandings require systematic evidence – something for which conventional wisdom has little need. Like any other science, sociology entails research that builds on pre-existing bodies of knowledge, is conducted according to carefully developed procedures, with results double-checked by experts. In order to understand – and improve – myriad aspects of food and society, then, sociological thinking is essential and strenuous efforts are needed to do it as well as possible.

This book introduces a set of perspectives which is not as widely known as the conventional wisdoms with which they are contrasted.7 They are also probably less widely known than other social scientific contributions to the study of food and eating such as those in psychology or economics, and are certainly very different from those that place a sole emphasis on diet and nutrition, on food science and technology, or on marketing studies of ‘consumer behaviour’. Sociological perspectives often lead in novel directions adopting less familiar angles. In turn, these angles reveal that social life and the place of food and eating within it is intricate and anything but neat and tidy. Some studies primarily use food as a ‘lens’ on aspects of social organization or of socially differentiated opportunities, providing a ‘window on the political’, revealing global trends or illuminating new v...