- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

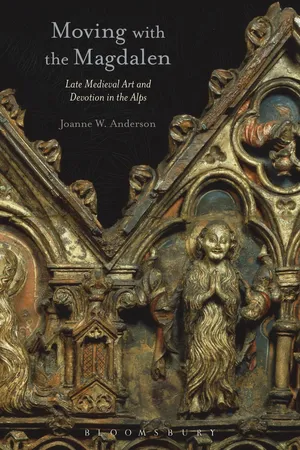

Moving with the Magdalen is the first art-historical book dedicated to the cult of Mary Magdalen in the late medieval Alps. Its seven case study chapters focus on the artworks commissioned for key churches that belonged to both parish and pilgrimage networks in order to explore the role of artistic workshops, commissioning patrons and diverse devotees in the development and transfer of the saint's iconography across the mountain range. Together they underscore how the Magdalen's cult and contingent imagery interacted with the environmental conditions and landscape of the Alps along late medieval routes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Moving with the Magdalen by Joanne W. Anderson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & European Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Pilgrimage Politics and Late Medieval Art

On 9 December 1279, Charles of Salerno, member of the Angevin ruling dynasty of the Kingdom of Naples, ‘discovered’ the body of Mary Magdalen in a plain marble tomb – and not a historiated alabaster one – in Provence.1 The saint had appeared in a vision to Charles confirming her true and final resting place and this led him to the crypt of Saint-Maximin on that fateful day. The relics were authenticated ten days later and retranslated into reliquaries for ritualized display.2 On 3 April 1295, nearly twenty years later, Pope Boniface VIII ratified the relics of Mary Magdalen held at Saint-Maximin allowing Charles to institute the Dominican order as the guardians of the sacred site.

The discovery of the relics in Provence may not constitute a classic furtum sacrum or holy theft, in which the physical relics are taken and transported elsewhere, but his act was nonetheless political in stealing attention away from a previous tradition of the Magdalen cult and its attendant art and devotional practices.3 Charles had challenged the authority of the Benedictine monks of Vézelay Abbey in Burgundy, who for over 200 years had claimed possession of the Magdalen’s relics, as legitimized by successive popes since 1050. It was a canny manoeuvre for the body of one of Christianity’s most important saints for political gain. But it also overturned the pilgrimage practices of hundred, if not thousands of people, from all walks of life across Europe who travelled from far and wide to venerate the relics at Vézelay in the hope of the remission of sins, of bodily cures, for personal devotion and for protection.

After the retranslation of the Magdalen’s relics in 1279 and certainly by 1295, such pious practices were entirely reorientated to Provence and its key devotional sites. These sites were the church of Saint-Maximin with its crypt, which held the tomb of Mary Magdalen and her companions, as well as the grotto of La Sainte-Baume on the nearby massif, a place visited during the Vezelian years of pilgrimage. The incorporation of the grotto represented a measure of continuity between the two pilgrimage sites that would convince the authorities and the faithful of its authenticity. Along with the new guardian order, namely the Dominicans, there was a redisplay of the relics to accompany the modified cult story and a fresh book of miracles was begun under the auspices of the third prior, Jean Gobi the Elder (1304–1328).4 Such a change in circumstances reinvigorated the cult and its international appeal. It can also be traced in a series of artworks that codified the shift in the second half of the thirteenth century, which are to be found in Florence and Assisi, but also in a village in the Western Alps.

This chapter examines the importance of this shift in the development of the Magdalen cult and its contingent imagery between France and Italy. It focuses on a late-thirteenth-century sculpted altarpiece from the Aosta Valley, near Turin, an artwork that responded to the change in cult circumstances in a most material way. The altarpiece is to be situated within a series of influential occurrences: the compilation and circulation of Jacobus de Voragine’s Golden Legend in the 1260s, the retranslation of the Magdalen’s relics in 1279 and their papal approbation in 1295. More significantly, the chapter addresses the influence on the altarpiece of the late Roman tombs in which the Magdalen relics were discovered with a particular focus on their formal qualities. This will be aligned with the influence of more contemporary types of relic containers. These objects helped to legitimize the new location of Mary Magdalen’s relics and, in doing so, codified a new iconography of the saint in this rural location.

A toll of devotion – Mary Magdalen in the Aosta Valley

The altarpiece in question depicting scenes from the life of Mary Magdalen was donated to the Museo Civico di Arte Antica in the Palazzo Madama, Turin in 1867 (Colour Plate 2).5 The original entry record of the museum notes that the large composite panel, dated to around 1295, is from the village of Carema, located at the southern mouth of the Aosta Valley. A more precise provenance of the altarpiece is unknown due to a lack of documentary records noting such information prior to its entry into the Madama collection.6 In contrast to mural paintings that often lie below layers of whitewash quietly waiting to tell their stories of lost visual cultures and patterns of devotion in the space that they physically defined, panels move and altar dedications change, often destroying vital contextual information. To make matters more complicated, the parish church of Carema has always borne a dedication to St Martin and no Magdalen chapels in churches exist in the immediate vicinity. Given that the provenance of the altarpiece is relatively firm, the question of why Mary Magdalen is even more pressing.

In medieval times, Carema was a small but strategically placed toll point on one of the most important pilgrimage routes in Europe, the Via Francigena. This route ran between Canterbury and Rome, with branches that connected it to other important sacred destinations, including Santiago da Compostela and the cult of St James. One of these branches passed through Switzerland and entered Italy through the Aosta Valley, with Carema a potential stopping point.7 The village fell under the feudal rule of the Vaillese family, but also served the vying lords of nearby Pont-Saint-Martin and Castruzzione, whose bridges and converging roads channelled merchant and other profitable footfall for the easy collection of taxes in this mountainous terrain.8 At such points of convergence, local communities were sustained by contact with a wider world. This included pilgrims travelling to cultic sites to see precious relics and experience places of contemplation, which might lie beyond the mountains in southern France or closer by at the Sacra Monte of Biella near Vercelli.9 Given its geographic locale and relative proximity to Provence, Carema was a prime location for devotion to Mary Magdalen with the production of the altarpiece evidencing a reaction to new patterns of pilgrimage.

The main corpus of the altarpiece is comprised of two horizontal planks of wood measuring around 205 cm in length and 143 cm in height. It is sculpted entirely from Swiss pine (cembra pinus) and retains much of its original polychrome with some traces of gilding. Four iron bolts at the outer extremities suggest that wing panels were once present, substantially extending the structure and its decorative potential. These wings would have closed around the central panel, making the altarpiece a container whose sacred content was revealed on appropriate feast days, as with the near-contemporary retable at Cismar Abbey (Grömitz, Schleswig-Holstein).10

Each painted figure, decorative feature and architectural superstructure of the altarpiece was individually carved and attached by glue and nails, including the miniature liturgical and dining apparatus in their respective scenes. Looking at the altarpiece obliquely, the dramatic cast of figures and their settings project strongly outwards from the support, creating a highly texturized surface with a depth of field enhanced by pockets of shadow and revelations in light. Such enlivened materiality both impels and sustains close contemplation of each episode by its bold configuration.

The sacred story is organized from left to right then right to left (boustrophedon style) along the horizontal. It begins on the lower register with the scene of Anointing in the House of the Pharisee. Mary Magdalen is crawling under a long table to anoint the feet of Christ, much to the shock of his fellow diners. She is squashed into this space, with her limbs spilling out audaciously onto the frame mouldings and into our space. The sculptor ensures that we look at the key action of Mary drying her spilt tears with her hair, despite the constraints of her position and clothing. Face, hand and foot are pivoted out towards the viewer. Christ also gestures downwards to her devotional act, encouraging emulation; an action familiar to pilgrims who had experienced crawling underneath or inside sacred shrines.11 The Magdalen’s act is thus a guide to penitential postures and ritualized behaviour. The Anointing is the largest scene of the Carema altarpiece with the greatest number of protagonists and is read right to left. To pull the eye back, we next encounter Mary Magdalen as myrrhophore. This time she looks directly out to the viewer with comely smile, blushed cheeks and heavily lined eyes. There is also a shift from horizontal to vertical positioning, a bodily rhetoric that declares her change in status from sinner to saint as confirmed by the presence of her halo. Mary is garbed in a red robe and blue dress. She holds an unguent vase, one of her key visual attributes, in her left arm while referring to it elegantly with her right. It is the only single-icon sculpture in the programme and occupies the midway point of the arcade (arch 5 of 11). The column to her immediate left also extends down to the edge of the dining table, ensuring that this icon serves as a resting point before moving into the next section. There we see the three Marys (Mary Magdalen, Mary Salome and Mary of Cleophas) arriving at Christ’s open tomb to anoint his body, as two soldiers sleep by its side.12 An angel sits lightly on the edge of the tomb with legs crossed, arm stretched towards the folds of the empty shroud; a detail one can only appreciate from a close and elevated range. The lower register of the altarpiece is completed by the scene of Christ’s appearance to Mary Magdalen in the garden, known as the story of the Noli me tangere. A single tree orchestrates their encounter, with its gentle curve enclosing the Magdalen as she kneels before her saviour (legs spilling out onto the frame again). Only her hands break the spatial divide by extending across the trunk. However, along with her eye direction and the upward thrust of Christ’s flag of the resurrection, the viewer is pointed onwards to the upper register.

The story continues with the Magdalen’s self-imposed exile in the wilderness, during which time her hair came to cover her entire body; an iconographic detail drawn from her apocryphal legend, marking a shift from the gospel-based accounts depicted before. This exile is visualized in two compartments articulated with tri-lobe round arches. In the right-hand side compartment, Mary Magdalen peeks out of a rocky cave as symbolic of a wilderness landscape that has spatial depth, to receive the heavenly manna (bread and wine from a flask) brought by a flying angel located in the quatrefoil above. On the left, the hirsute saint is lifted to the heavens by a pair of tumbling angels. Such a celestial experience is conveyed by the absence of any earthly setting, but also through contrast with her cave-dwelling existence in the previous compartment.

The large central compartment under the main gable presents Mary Magdalen kneeling at an altar to receive her last communion; highly appropriate for a devotional object designed to sit on an altar. The Eucharistic wafer, individually carved, is placed delicately in the saint’s mouth by Bishop St Maximin, her compatriot from Judea as recounted in the Golden Legend (Colour Plate 3).13

An acolyte stands behind St Maximin holding the episcopal crozier, another well-handled detail that draws attention to the para-liturgical equipment set on the altar. Moving left to the final compartment, we encounter the death of Mary Magdalen. Her body, clad in thick waves of hair, lies prostrate at the base of the dividing column, almost like a Tree of Jesse, with delicately carved wrists neatly crossed. Two angels (badly damaged) in the upper left section carry the Magdalen’s soul in a cloth of honour up to heaven, which, following visual conventions of the time, is symbolized by an eidolon or small person (assumptio animae).14 Two more angels swing censers in the quatrefoil above and to the right of the scene. We thus end with the body of the saint, her relics, on display after a series of tableaux that cover the key themes of penitence, redemption, revelation, vision, authentication and sanctity. This imagery was ideal for passing pilgrims and profitable for the local community.

In its original state, the altarpiece would have been a sumptuous-looking object remarkable for its bravura carving and delicate finish that pointed away from its local materials of manufacture. It is attributed to t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Pilgrimage Politics and Late Medieval Art

- 2. Regulating the Mountain Parish Saint

- 3. Networks of Devotion in Bozen

- 4. Framing Pilgrimage Practice in Tyrol

- 5. Mining Devotion in the Mountains

- 6. Alpine Workshops and Artistic Transmission

- 7. Devotion and Resurrection in Pontresina

- Coda: The Alps as Kunstlandschaft

- Bibliography

- Index

- Imprint