![]()

INTRODUCTION

Aijaz Ahmad

To be a ‘Marxist’ is to continue the work that Marx merely began, even though that beginning was of unequalled power. It is not to stop at Marx, but to start from him … Marx is boundless, because the radical critique that he initiates is itself boundless, always incomplete, and must always be the object of its own critique (‘Marxism as formulated at a particular moment has to undergo a Marxist critique.’).

– Samir Amin, The Law of Worldwide Value

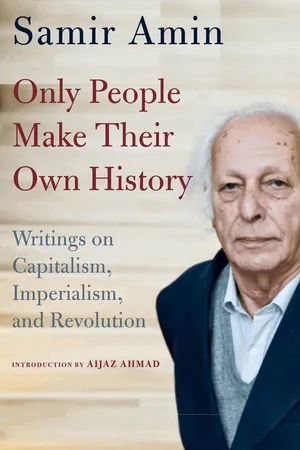

Samir Amin (1931–2018) was one of the grand intellectuals of our time.1 A distinguished theoretician, his life of political activism spanned well over six decades. A socialist from an early age and trained as an economist, he insisted that laws of the economic science, including the law of value, were operationally subject to the laws of historical materialism. Trained also as a mathematician, he avoided too great a mathematization of his concepts and kept algebraic formulae to a minimum in even the most technical of his writings. The ambition always was to retain theoretical rigour while also communicating with the largest possible number of readers—and activists in particular—through exposition in relatively direct prose. His readership, like his own political activism, was spread across countries and continents.

Amin came of age in the 1950s, when the wave of socialist revolutions seemed to be very much on the ascendant and the old colonial empires were being dismantled across Asia and Africa. Communist parties and socialist movements had emerged in these continents, more in Asia than in Africa, even before the Second World War. Onset of the postwar period witnessed immense expansion of revolutionary activity—the Chinese revolution, Korea, the onset of revolutionary liberation movements in Indochina and so on. With the notable exception of China, however, most countries in these continents had produced relatively little original work in the field of Marxist theoretical knowledge. Study of any sort of Marxism largely meant explication and/or translation of texts produced elsewhere, and that too was confined to the very brief texts or extracts from the Marxist classics or exegeses done in Britain, France or the Soviet Union. This now began to change, in several notable ways. First, we witness the rise of a new generation of Marxist scholar-activists across Asia and Africa over the very years when the colonial empires were getting dismantled. Second, a number of these new intellectuals, often associated with communist parties or national liberation movements, bring into their work increasingly sophisticated knowledge of the more fundamental of the classics: the major works of Marx, Lenin, Luxemburg, Bukharin, Kautsky and others. Third, attention shifts to extended, rigorous analyses of (1) the historical development, modes of production and class structures not so much of Europe as of Asian and African countries, and (2) the very elaborate mechanisms involved in the exploitation of the imperialized countries, i.e., the process whereby values produced in the colonies were appropriated for accumulation in imperialist centres.

Mention of a few dates should clarify this. Thus, for example, Amin submitted his 629-page doctoral dissertation to the University of Paris in 1957 and published it much later as the two-volume Accumulation on a World Scale (French edition 1970; English translation 1974). In the course of roughly those same years, India witnessed the publication of three books that were foundational in the making of Indian Marxist historiography: D.D. Kosambi’s An Introduction to the Study of Indian History (1956), Irfan Habib’s The Agrarian System of Mughal India (1963) and R.S. Sharma’s Indian Feudalism (1965). Across the oceans, in Latin America, all the founding texts of Dependency theorists—Theotonio Dos Santos, Celso Furtado, Ruy Mauro Marini, Andre Gunder Frank, and others—also appeared in the 1960s and early ’70s.2 Theoretically, Amin was much closer to Paul Baran who published The Political Economy of Growth in 1957, the year Amin submitted his mammoth dissertation. The great classic of Marxist political economy that Baran co-authored with Sweezy, Monopoly Capital, followed soon thereafter, in 1966. Anatomies of imperialism had thus arrived at the very centre of new Marxist thinking across the world, and Marxism itself had become a powerful tool for independent thought and research across the Tricontinent. On both these counts, Amin’s dissertation would appear to be among the first texts re-fashioning the contours of postwar Marxism in a very particular way, as we shall argue below.

Amin was proficient in several languages but wrote primarily in French. He was a stunningly prolific writer, producing books and articles with great speed until death itself silenced that fertile mind. Not all his work is available in English. Some of the translations have appeared elsewhere but, on the whole, Monthly Review Press has been by far the most devoted publisher of his work in English translation. This collection brings together eleven of Amin’s essays that the magazine has published since 2000. There are others that appeared in MR during this period.3 The objective here is to assemble a not too cumbersome a collection of his essays that would elucidate some of the most fundamental coordinates of Amin’s thought in the closing years of his life. The introduction here is designed not to explicate those texts but to situate them in the larger fabric of his life in which the personal, the political and the theoretical were meshed together in a tight weave.

I

Samir Amin published two books of reflections on his own life. In Re-Reading the Postwar Period, he offers his own reconstruction of his political views and theoretical positions as they evolved from one decade to the next, up to the beginning of the 1990s.4 The fact that he arrived in Paris to start college in 1947, the year India got its independence, reminds us that his adult life coincided with exactly the period he reviews in that book. He was a young communist and a student activist in France during the great, bitter wars of liberation in the French colonies of Vietnam and Algeria. Dismantling of the British and French colonial empires were the epochal events of his youth. The overlap between colonialism, postcolonial imperialism and capitalist accumulation logically became the central occupation in his intellectual life as well as in his political activism for the rest of his life. In Capital and related works, Marx had shaped the science of the capitalist mode of production as it had evolved in Europe, Britain in particular, up to his own time. In other texts, such as the Grundrisse and the much later Ethnographic Notebooks, Marx said much about the world outside Europe but mostly about precapitalist formations. He wrote extensively and often very perceptively about colonialism but mostly at the level of factual description and political denunciation, with only a few scattered remarks of lasting theoretical import. For Marx, a compulsive globalizing tendency was inherent in the very mode of functioning of capital itself. However, aside from this repeated prediction, the actual corpus of his work did not encompass, nor was the third quarter of the 19th century a propitious time to produce, a theory of a the capitalism that was to become a fully globalized mode of production—not only of appropriation, extraction and circulation—in the form, first, of colonizing imperialism and, then, even more strongly after the dissolution of the old colonial empires. Amin’s distinctive undertaking in his doctoral dissertation that was later published as Accumulation on a World Scale was to apply the theoretical categories of Capital to the study of the capitalist mode as it unfolds globally through the agency of colonialism, putting in place structures of exploitation and accumulation that were to greatly outlast the colonial era per se.5 For him, as for very few other Marxists, the end of the colonial period marked a decisive turning point in the history of human freedom that opened up new avenues for liberation struggles for peoples of the Tricontinent—but not a fundamental break in histories either of capitalism or of imperialism per se. This historical ambiguity of that conjuncture is best witnessed in the fact that the quarter century, 1945 to 1970, in which those colonial empires were largely dissolved, has also gone down in history as the Golden Age of Capital.6 This intent to read Marx rigorously but creatively in light of the later evolution of the capitalist mode remained a major thread in Amin’s work all his life, up to The Law of Worldwide Value (2010) and beyond.7 We shall return to this presently.

Re-Reading the Postwar Period recounts the stages of his own intellectual development in relation to the main features and events of that period. The latter portions of the other memoir, A Life Looking Forward, reconstruct that same politico-intellectual itinerary in more personal terms but it is in the earlier sections of the book that we get a vivid narrative of his growing up in a rather unique family and his early orientation toward revolutionary politics, so that all of his life, beginning to end, seems to cohere into an integral whole.8 This more personal memoir opens with a simple sentence: ‘Ancestors do matter.’ This then is followed in the same opening paragraph with: ‘Certainly my own family, on both my mother’s and father’s side, reminded me from time to time that the education they were giving me was a ‘legacy’ to which they were firmly attached.’ With an Egyptian father and a French mother, this ‘legacy’ had two sides to it: ‘… my parents had actually met in Strasbourg as medical students in the 1920s. It was a happy meeting between the line of French Jacobinism and Egyptian national democracy—in my view, the best traditions of the two countries.’9

The father’s side was Coptic upper class, part of a cosmopolitan mini-world of Christian and Muslim Egyptians, Greeks, Armenians, Maltese as well as French and British émigré residents sprinkled all over Cairo but spread more widely over Alexandria, Port Said and more generally across the region where the fertile Nile delta of Lower Egypt meets the country’s Mediterranean coast. The family, which included well-known publishers and writers of the 19th century, was part of a larger milieu that valued secular democratic convictions, higher learning, professional standing, and a sort of liberal bourgeois enlightenment that looked down on all sorts of feudalism and conservatism. His father, a doctor by profession and a bourgeois with social conscience, was opposed both to British colonialism and to monarchy, and he preferred communists to demagogic nationalists, including Nasser. On the other side of the family, Amin quotes his maternal grandfather, a freemason and a socialist, as once explaining to him, ‘we Alsatians helped to make the [French] Revolution and we know the meaning and price of liberty’. As for the maternal grandmother, she, ‘born soon after the Paris Commune in 1874 … was one of the descendants of the French revolutionary Jean-Baptiste Drouet, who played a role in the arrest of Louis XVI at Varennes in 1791 … My grandmother was quite proud of this ancestor, who was also active in the Babeuf movement…. As for my grandmother’s name, Zelie, this was quite fashionable in the 19th century, but she told me she had been given it in homage to the Communard Zelie Camelinat’. This grandmother disliked religion and preferred to revive the Enlightenment slogan ‘No God, no masters’, which 19th century Anarchists like Bakunin shared at the time with Marx.

Democratic Wafdism, left-oriented anti-colonialism, and anti-monarchism on one side; family memory of Republican and revolutionary regicide, Babeuf-style communism and the Paris Commune on the other side: a pleasing and formidable ‘legacy’ indeed! Amin grew up in this loving, happy, sprawling and well-integrated family with clear-cut political views and historical moorings, and he went to school during the Second World War when Britain was still a colonial presence and a master of the Egyptian monarchy while a German advance through the whole region was at one point a distinct possibility. His secondary school, a French Lycée, was not immune to various political currents in Egyptian society: monarchists and anti-monarchists, nationalists of various stripes, and of course communists. Amin writes of being firmly in the communist group of students. Upon finishing secondary education he officially joined the Egyptian communist party. When Andre Gunder Frank asked Amin’s mother as to when in her opinion her son had become a communist, the mother good-humouredly recounted a childhood anecdote and conjectured that it was perhaps at the age of six.

The ten years that elapsed between 1947 when Amin first arrived in Paris for post-secondary education—joining the French Communist Party quite swiftly, having joined the Egyptian communist party upon finishing secondary education—and 1957 when he submitted his doctoral dissertation were of course the years of the great wars of liberation in the French colonies of Indochina and Algeria, as mentioned earlier, leading to bitter polarizations within French society between pro-war and antiwar segments of activists, intellectuals, university faculties and students, and the general population itself. That was also the last decade of the French Communist Party’s (PSF) very formidable role in French politics, before the decline began, and of Marxism as the central issue in French intellectual life (indicated, for instance, by Sartre making his passage from Existentialism to Marxism10 and Merleau-Ponty’s contrasting renunciation of Marxism in favour of a left-liberal position). France was also home to substantial enclaves of immigrant working class drawn from its North African colonies, Algeria in particular. Paris itself had been a major intellectual centre for anti-colonial students, activists, writers and intellectuals from the African and Caribbean colonies since the 1930s, when luminaries such as Senghor and the two Césaires (Aimé and Suzanne) were among the group that invented Negritude, a literary movement deeply marked by political and philosophical positions of the left and often combining a Pan-African ideology with Surrealist poetics.11 Fanon (a student of Aimé Césaire) arrived in 1946 from yet another French colony, Martinique, to study psychiatry in Lyon, in an institution where Merleau-Ponty, a key influence on Fanon, was teaching philosophy. Amin arrived in Paris a year later, in 1947, and Alioune Diop founded the legendary journal Présence Africaine that same year, going on then to establish the equally legendary publishing house, Editions Présence Africaine, two years later in 1949. In 1956, the year before Amin completed his doctorate, the publishing house—by then the world’s foremost publisher of writers of African origin (writers of the Black Atlantic, we might now say)—organized the first International Congress of Black Writers and Artists (for which Picasso designed the poster). That ten-year period witnessed the publication of four classics of anti-colonial literature that were centred very largely on the broader African experience: Fanon’s two texts, Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism (1961) and Albert Memmi’s The Colonizer and the Colonized (1957).12 Those are not books of political economy but what they shared with Amin’s dissertati...