![]()

Chapter 1

The Luck of the Irish

The 2013 horsemeat scandal which was discovered by the Irish enforcement teams and led to a new dawn in the fight against food adulteration. The stakes were raised – It became a crime rather than a misdemeanour. Never again will food fraud be punished in a magistrates court, it's the crown court from now on with a food crime unit on the tail of the fraudsters. This chapter gives a unique insight into how it was detected, how to avoid or at least try to avoid detection and the trials. How the regulators reacted, at the time there was no nationally agreed system for prosecuting and detecting this fraud. The prosecutors had to ‘cut their teeth’ and learn how to prosecute and sentencing guidelines had to be written for Judges.

1.1 A New Dawn

The world changed with the discovery of horse passed off as beef in 2013. Well, at least the enforcement world in the UK changed; it would never be the same again, and this would impact across the European Union (EU) world of enforcement too. Why? Horse has been passed off as other meats before, and there is a history of other species, for example lamb and goat, being sold as other more expensive meats too. Generally, the public is apathetic about these food scandals; they come and they go. The media kick up a little storm, and then the food scandal fades from the memory. Food seems to be treated differently; food fraud wasn't called fraud, it was called by many other names but not fraud. So why was this case different? Horsemeat was passed off as beef in foods sold in Sweden, France and the UK. The whole of the food industry was caught off-guard and this caused a reaction amongst the public and particularly politicians, who responded to media and public opinion. How dare someone pass off horse as beef! This scandal reached the very top, even the Prime Minister was involved. The perpetrators will feel the full force of the law. Was this the start of a new era in food enforcement?

Substitution of beef with horse became a major crime; at the time, it was not on the horizon of virtually anyone involved in food either as a business, retailer, manufacturer, supplier or the enforcement agencies. It should have been, and the Irish were alive to the possibility. The fraudsters discovered an opportunity to use a plentiful supply of cheaper horsemeat and substitute it for the more expensive beef and make a financial killing; and they took full advantage – the perfect fraud? The disguise was simple; mince the meat and sell it as minced beef. Thousands of consumers, retailers and food businesses were ripped off by these thieves. They used a web of deception, buying horsemeat and beef from separate suppliers, mixing the two, then passing the combined horsebeef mince off to the ‘trusted suppliers’ of some of the largest retailers and food businesses to sell on the fraudulent produce to their clients who were all naive to the issue. They successfully duped everyone, including the consumer.

The perfect fraud was helped by the fact that those checking the mince would need to carry out testing for a specific species, in this case horse, as there was no simple test to check for all species. Testers needed intelligence or a hunch to know that they should test for horse. Early in 2013, I asked public analyst colleagues throughout the UK if any were looking for horse in the previous year. With two exceptions, all replied no although a few looked for substitution of pork, lamb and beef species. One of the Welsh public analysts did test for horse, and their nine samples gave negative results. The Irish authorities didn't follow the enforcement crowd as their routine investigations looked for horse (using the other public analyst), and they found horse where beef was declared. Did the fraudsters know that the testing regimes helped their fraudulent activity go undetected? Did they have inside knowledge or were they just lucky and had access to an opportunity; namely, to buy and mix horsemeat and beef?

Food fraud was a whole new ball game as, previously, adulteration of food was the preferred charge for regulators. This simply needed analytical proof that the food was not compliant with the regulations, i.e. checking meat species and confirming that pork was not present when beef mince had been declared. Food enforcement officers were comfortable with this approach as it involved straightforward analysis and, if necessary, a routine prosecution through the Magistrates Court. It was a reliable system which had served them well since 1860. The old reliable system may have worked well, but it didn't focus on fraud or finding the brains behind a fraud – the criminals; it simply focussed on proving that food was not of the required standard at the point of sale. This resulted in fines, often relatively small. Did this make the fraud worth the risk; after all, the gains could be far more significant than any fines? The risk of getting caught was hardly an issue if the fines were small and the enforcers were looking elsewhere. Something needed to change.

Yet, it has to be said that to prosecute the offence of fraud is far from straightforward. It is necessary to demonstrate that the defendant's actions involved five separate elements:

- false statement of a material fact;

- knowledge on the part of the defendant that the statement is untrue;

- intent on the part of the defendant to deceive the alleged victim;

- justifiable reliance by the alleged victim on the statement; and

- injury to the alleged victim as a result.1

Trying to gather evidence to prove intent was a complete departure from the norm for food enforcement officers. Police colleagues were needed to maximise the chances of a successful prosecution. Politicians wanted action and demanded that the key culprits were found and prosecuted. A new dawn in public protection arrived, and would food enforcement ever be the same again?

1.2 How to Commit Fraud in the Meat Trade

Meat is a commodity which can be traded like any other and is classified as follows:

- primal cuts: these are the best cut from an animal – for example, loin or rib and sirloin – and may be sold whole or cut further. These are harder to forge as experienced butchers may be able to identify different species by sight;

- trim: the meat removed from a carcass after the primal meat is removed. It is often minced and used for manufacturing burgers, for example. Trim is sold using a numerical classification such as 80/20, lean meat and fat contents, respectively; and,

- mechanically separated or recovered meat: as its name implies, this is the lowest quality of meat removed from the carcass. It is forced through sieves using high pressure to separate the bone and produce a ‘meat slime or paste’.

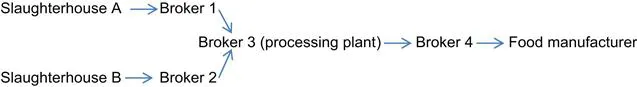

The commodity can be traded between many brokers without leaving the original slaughterhouse and is eventually sold to a manufacturer for processing. This is because many brokers do not have the facilities to store meat in large quantities. Many in the food industry believe that, the longer the line of brokers, the more the risk of fraudulent activity as this increases the potential for a web of deceit. The current defence against fraud of ‘one up, one down traceability’, espoused by some food businesses and recommended by regulators, may aid this. As the name implies, the principle is that each member of the chain (sometimes referred to as a web to demonstrate the complexity and world-wide nature of the process) is responsible for ensuring the traceability of the product from the adjacent members within the chain. My employers and some of the largest retailers moved away from this approach a few years before Horsegate and demanded very short supply chains so that the manufacturer personally knew the origin of the food. This builds closer partnerships and dramatically reduces the likelihood of fraudulent activity.

In the case of a fraud involving beef and horse, the two meats must be combined, which more than likely means sourcing meat from two slaughterhouses. This is to keep the number of knowledgeable people to a minimum and process the meat within the chain utilising an unsuspecting ‘trusted broker’ with an excellent reputation to sell to the food manufacturer. A schematic for such an operation might be as follows:

Slaughterhouse A might be the supplier of beef and Slaughterhouse B the horse.

The slaughterhouses, other brokers and manufacturer would be blissfully ignorant of the fraud and the fraudster would seek to keep it that way, trying to ensure that as few people as possible were alerted.

At every stage, documentation must support the consignment and be available for inspection when required, so to disguise a fraud, the documentation must be altered to ‘cover the tracks of the fraudster’. This type of forged paperwork starts to build the required elements for the full offence of fraud.

Horsemeat can be legally traded throughout the EU; in some member states, it is prized for human consumption (France, Hungary, Italy and Belgium). In others, such as the UK, it is not a meal choice, possibly because the UK public see a horse as a pet and find it abhorrent that it could be served up on a dinner plate. There are regulations concerning abattoirs and the processing of horse and beef to ensure that the two cannot be ‘inadvertently’ mixed, and the precise nature of the meat must be as declared on the label provided by the slaughterhouse.

1.3 The Investigation

During 2012, two investigations being carried out by enforcement officers of the Food Standards Agency Ireland (FSAI) were a survey at wholesalers of beef products and samples of foods taken at food retailers (market surveillance). The two initiatives run by the Irish authorities were not connected.

The investigation which looked at wholesalers eventually led to a sizeable fraud prosecution and arose from a random sampling visit to Freeza Meats Ltd in September 2012 by environmental health officers from Newry and Mourne District Council.2 This time, pallets of frozen meat trim were found which were being stored on behalf of McAdams Foods. The labels suggested the meat had originated from Poland and it was being unloaded at McAdams. In fact, this was a lie as the meat had been unloaded elsewhere and the documentation was falsified to hide this information. Further checks on the consignment in October 2012 and early 2013 revealed an identification chip from an Irish pony and a polish horse called Victor.3 The pallets were tested and proved positive for horse and beef DNA in various mixes.

The retail survey was linked to a series of campaigns which had run across a range of foodstuffs over the previous seven years, assessing what was available for sale on the high street. This sort of investigation has been carried out by many enforcement officers across the UK, although the numbers are reducing dramatically as budget cuts bite. It is interesting to note that the Irish should be praised for not slavishly following a system of risk-based monitoring which doesn't incorporate street surveillance, i.e. ‘just checking’ what is available for sale on-the-market through retailers. In recent years, risk-based monitoring has become in-vogue as it allegedly reduces the burden on food businesses and the workload for short-staffed government enforcement agencies that might be strapped for cash. Had this been followed slavishly, horsemeat fraud would never have been detected.

In 2012, the retail focus was on meat products such as foods containing beef, for example lasagne, salami and beefburgers, and checking them for authenticity using sophisticated DNA techniques to test for pork, horse and beef.4 The first positive result from this survey looking for horse DNA was revealed on 10 December 2012.4 Consequently, more samples were taken for DNA profiling on 18 and 21 December 2012.4 The samples were sent to IdentiGen (Ireland) and Eurofins (Germany) with an additional request to quantify the amount of horsemeat found. Results were received on the 11 January 2013, and these confirmed that nine out of the ten burger samples submitted tested for low levels of horse and that the tenth contained around 29% horse. The product concerned was beefburgers manufactured by Silvercrest for Tesco.5

On 14 January 2013, the FSAI informed the Department of Health and the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine in Ireland of the final results of the retail survey. On the same day, it also informed the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in the UK.4

The extensive testing regime yielded the following results:

‘Of the 31 beef meal products (such as cottage pie, beef curry pie or lasagne), all were positive for bovine DNA, 21 (68%) were positive for porcine DNA and none were found to contain equine DNA. Only two of these beef meal products declared on the label that they contained pork, which was found at very low levels and therefore we considered its presence may be unintentional and due to cross-over from processing of different animal species in the same plant.

Of the 27 burger products analysed, all were positive for bovine DNA, 23 (85%) were positive for porcine DNA and 10 (37%) were positive for equine DNA. Most of the burgers positive for porcine DNA were not labelled as containing pork which was found at very low levels and again we considered its pres...