![]()

1

SLUDGE

WILLIAM DUNCAN FARMED A SMALL PROPERTY near Heathcote, in central Victoria, in the 1880s. He grew wheat and oats, and grazed sheep and cattle on his 120 acres, but mine tailings were destroying his land. They had filled the creek to the brim and oozed over his paddocks to ruin the crops. When stock tried to reach the creek they got stuck in the mud, and the water was too thick for them to drink. A dozen large cattle had been lost in the neighbourhood, and others were injured when the farmers used bullocks to haul them out of the muck.

Duncan wasn’t alone in his struggles. Farmers and graziers all over Victoria were seething about the sludge problem. After thirty-odd years of watching mine waste fill their waterholes and inundate the land that was their livelihoods, they had just about had enough.

At the Pink Cliffs Geological Reserve just outside Heathcote, the source of the sludge that covered Duncan’s land is brutally obvious even now, a century and a half later. The blasted lunar landscape of pink, yellow and orange rock is all that remains from the decades of hydraulic sluicing that occurred here (see picture section). Much of the sluicing was carried out under the supervision of Thomas Hedley, a Canadian-born miner who managed the McIvor Hydraulic Sluicing Company. In the 1870s, the company constructed a channel, or water race, almost fifty kilometres long to bring water from the hills near Tooboorac. At full capacity they used more than twenty million litres of water every day, sending massive volumes of sludge into McIvor Creek. Hedley agreed with the report from a government enquiry in 1886 that the waste water was as thick as porridge, but claimed that the shallow fall of the land meant there was no way to hold back the sludge in retaining dams and, anyway, the cost would be crippling – it was all he could do to make the claim pay as it was. He had heard complaints from farmers downstream about sludge, but he was a goldminer and, frankly, sludge was their problem.1

Sludge exacerbated the impact of floods. In September 1870, days and days of incessant rain at Castlemaine poured water into creeks already choked with mining debris. The creek waters rose and covered the flats of the Chinese camp, turning it into a lake and ruining stores and buildings. Bridge footings became sludge traps, forcing the floodwaters up the banks and roads. At the foot of the hill near the gaol, water rose four feet inside people’s houses. Sludge from more than 300 puddling mills buried fences and destroyed gardens.2 The reactions of locals to the drama were fairly measured – it had happened before and no doubt it would all happen again.

Sludge could also be a death trap. Two-year-old William Hamilton wandered away from home near Maldon one afternoon in November 1868. His father and neighbours spent a frantic night searching for the toddler, but by the time they found him the next morning he was lying face down, dead, in a sludge hole. In 1862, William Dow was killed at Porcupine Flat near Ararat when a shaft adjacent to his own collapsed, burying him in sludge and water. A similar accident smothered and killed nineteen-year-old William Lewis at Blackman’s Lead in 1858. In 1860, Chinese miner Ah Fong was working a sluicing paddock at Fryers Creek next to one that was already filled with twelve feet of sludge. The wall dividing the two paddocks gave way and the sludge rushed in, burying and killing the young man before his brother could rescue him (see picture section).3 There were many other sad examples of death and injury from the sludge menace.

Sludge was the dark side of the gold rush. Payable quantities of gold had first been announced in Victoria in 1851, igniting a mining boom that was heard and felt around the world. Hundreds of thousands of migrants rushed to the new colony, eager to make new lives for themselves. Few ultimately made fortunes via gold, but most found the social and economic opportunity they craved. Gold rapidly transformed Victoria from a sleepy pastoral outpost into one of the richest and most exciting places in the British Empire. The upheaval of the gold rush was the catalyst for political reforms, such as universal manhood suffrage and the secret ballot. It paved the way for widespread home ownership and underpinned the birth of the union movement.4 The gold rush took its place among the most important series of events in Australian history. But all that wealth came at a cost, and most of that cost has been forgotten.

‘What is sludge?’ asked the Geelong Advertiser in an 1859 editorial:

It is the Colony’s share of the produce of gold-digging … When all the other glories of a gold field are departed, the sludge will remain as a monument, in perpetuo, of wasted energies and a false policy … The sludge is rolling down, like a lava-tide, upon the cities of Ballarat and Sandhurst, threatening to submerge them, and thus preserve them, like Pompeii or Herculaneum, for the delectation of antiquaries a thousand years hence. No less overpoweringly does the avalanche of imported sludge shoot into the seaboard towns, bearing down [on] all native industry.5

In 1859 Geelong was a full two-day coach journey from the source of sludge on the goldfields, and yet the threat was making its presence felt even at that distance. On the goldfields themselves the situation was much, much worse. Poor Jacques Bladier, a prominent viticulturalist, was up to his neck in it.6 He grew prize-winning fruit in his orchards and vineyards along Bendigo Creek at Epsom. Year after year Bladier’s grapes had taken top prize at the annual Bendigo agricultural show, and with them he made wine that was the toast of the colony. Now Monsieur Bladier watched helplessly as the rising sludge tide from Bendigo’s mines gradually suffocated his vines and choked his fruit trees. He built levee banks five feet high to protect his orchards, but still the sludge came, flowing over the levees and making a desolate wasteland of his beautiful, verdant gardens. Monsieur Bladier’s land was already Pompeii.

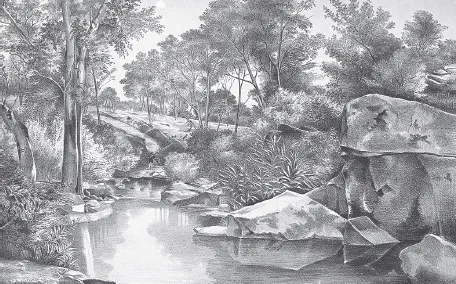

Sheepwash Creek near Bendigo, 1863

The landscapes of the goldfields had changed very quickly. Just a few years earlier the Bendigo valley was carpeted with green grass and dotted with beautiful gum trees, while its wattle-shaded creek banks sloped down to waterholes full of sweet, clear water. The site that was to become Beechworth had originally been a wooded plateau encircled by tree-clad hills, dipping gently towards a quiet-flowing creek in a gully. When the first miners arrived at Creswick Creek in 1852 they described the exceptional beauty of the broad flats covered with long green grass, reeds and trees, and the clear water of the creek bubbling past. But sludge brought an end to all that.7

‘Sludge’ was the colloquial word for the thick, semi-liquid slurry of sand, clay, gravel and water that flowed out of mining operations in Victoria. Farmers likened it to porridge. In California they called it ‘slickens’. Experts had more technical definitions. According to the 1906 Annual Report on Dredge Mining and Hydraulic Sluicing, sludge was water that contained ‘more than 300 grains per gallon of insoluble material’, such as clay, mineral and metal. The Dredging and Sluicing Inquiry Board of 1914 decided it also included ‘quartz boulders and gravels intermixed with clay and earth’. Sometimes miners distinguished between the fine liquid clay portion (slimes or slums) and tailings, which could be either the sands that resulted from crushing ore in stamp batteries, or the cobbles and boulders that were stacked in piles on alluvial claims (mullock). It all created a mess.

At times people tried to put sludge to good use. In 1859 a potter at Ballarat used sludge to make well-fired chimney pots. The specimens were described as ‘beautifully smooth, of fine texture and [ringing] as soundly as a bell’.8 Thomas Ramsay was a farmer at Newbridge who believed a little sludge on his land was a good thing. Four inches or so was ideal, so he could raise part of the original soil with the plough and mix it with the sludge. In the late 1850s, the Bendigo Sludge Commission proposed using sludge to build sixteen miles of railway embankment on the line going north to Echuca. The Eaglehawk Public Gardens (now Canterbury Park) were formed from the ‘judicious use of sludge and tailings’.9 Council workers dug out hundreds of loads of gravelly sludge from Jim Crow Creek and spread it on the roads around Daylesford. Contractors building the Geelong water supply system got gravel for their concrete from mine tailings in the Moorabool River below Dolly’s Creek and Morrisons.10 Sludge was also valued by some for the leftover gold it contained. No matter much they tried to use it, however, more and more was produced.

For miners who wanted to reprocess sludge and tailings to extract residual gold, the question of who owned the sludge was quite important. If it was stacked on a claim or held in a retaining pond it remained the property of the miner, but if it flowed down a creek it became part of the waterway and thus owned by the Crown. When it spread out over a floodplain and onto a paddock it was the farmer’s problem. The 1897 Mines Act legislated that tailings and sludge became the absolute property of the Crown when a mining lease expired or was abandoned. The minister could then issue a licence for someone else to treat the material.

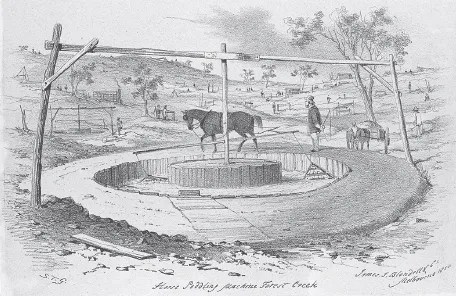

In the mid-1850s, Bendigo miners collectively discharged as much as sixty-seven million litres of sludge each day into Bendigo Creek. That meant nearly 44,000 tonnes of dirt were sent downstream from the Bendigo diggings alone every single day. That was the considered estimate of James Sandison, a thoughtful and observant man who studied Bendigo’s sludge in detail. Sandison was a miner himself and worked the puddlers at Bendigo’s White Hills. A puddler was a large ring-shaped trough in the ground, used to separate grains of alluvial gold from heavy clay soils (see figure on page 15). Ideally it was built on a bit of a slope, so water could flow in and sludge could flow out. Soil and clay were dumped in the trough, mixed with water and stirred so that the heavier gold sank to the bottom. After the water was released the gold could be scraped up and saved. The water that drained away was thick and viscous with clay. It had been turned into sludge.

Sandison’s calculation of the quantity of sludge was based on his own working day, and those of his neighbours. He started with the size of the cartloads of washdirt that miners brought to the puddler: ‘a load of stuff is a cubic yard, that is a ton … those I know and nearly all do that’. He multiplied the size of the load by the number of loads a puddler could process in a day – twenty-two loads, ‘a very low average’. (A contemporary of Sandison’s, William Kelly, believed the average number was more like sixty loads per day.) Sandison then multiplied the daily loads by the number of puddlers operating at the time. ‘There are at present’, he recorded, ‘2000 puddling mills at work. There is a larger number of mills than that in existence, but they are not at work.’ In this way, Sandison worked out the total amount of washdirt processed by the entire Bendigo goldfield, arriving at the considerable sum of 132,000 cubic yards (100,000 cubic metres) of sludge every twenty-four hours, two-thirds of it water and one-third silt and clay. He described a ‘high tide’ of sludge every evening around eight p.m., as the results of the day’s work flowed downstream to the flats at Epsom. He knew that it travelled at a rate of 3.5 miles an hour, because he had walked alongside it.11

Horse puddling machine, Forest Creek, 1855

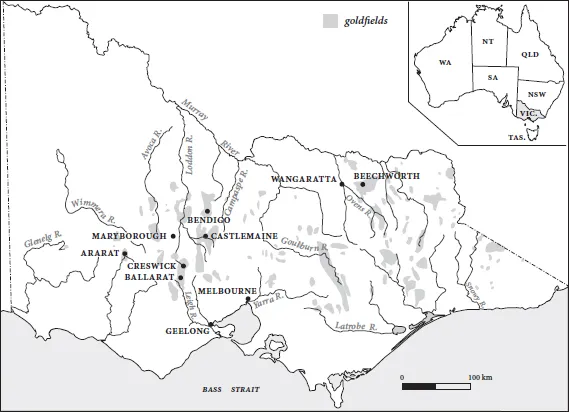

Map of Victoria’s goldfields

James Sandison studied the sludge because he could see the damage it was causing, and he wanted the authorities to build a drain to divert it away from the diggings. When the Victorian government called the royal commission into Bendigo’s sludge in 1859 Sandison told them what he knew about the problem. The commissioners heard a great deal of evidence, and they saw the situation for themselves. They could see that some of the sludge was trapped in abandoned diggings even before it reached Bendigo Creek:

large areas may be seen of partially worked ground which have been overflowed by the sludge and rendered almost worthless … [the sludge] has spread in vast mud estuaries … in some instances it has risen to so great a height that the machines themselves have been totally submerged … [The] sludge has attained a height of twelve feet above the level of the old workings.12

Following the commission’s report a short drain was built and sludge continued to flow into the creek.

When the commissioners returned in 1861, those who lived downstream told graphic tales of the damage (see figure below). Sandison, now working as an inspector of reservoirs, was back, but he was representing his neighbours rather than his mining colleagues. We can only imagine his frustration as he described the businesses and properties destroyed in the years since he first spoke to the authorities. He described land ‘covered by sludge to the extent of four feet and a half … [It was] the finest garden in Victoria [and is now] a perfect sea of sludge, and a great many of the trees are dead.’13 The garden he described belonged to his neighbour, the aforementioned Jacques Bladier, he of the vanquished grapes. When the sludge came, Bladier had lost dams, we...