![]()

![]()

Introduction

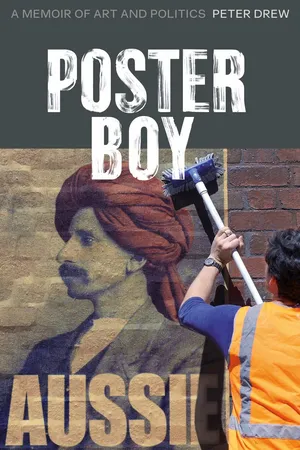

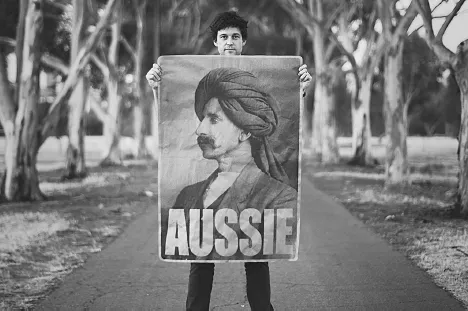

For the past five years I’ve stuck up thousands of posters across Australia in an effort to challenge and expand our national identity. It started with a focus on Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers, but with each new poster design the project’s scope has grown to encompass our broader national mythology. I’ve been rewarded with attention, accolades and praise.

Given my choice of occupation, you might expect that I have unshakable convictions about social justice and human rights, but I don’t. I’m sometimes called an activist, but it’s not a label I enjoy. I don’t have a personal attachment to any particular cause or marginalised group. I don’t even like political art. Given all this, why do what I do? That’s the question I’ve been asking myself lately, with nagging persistence.

Sometimes journalists ask me the same question, and my answer is usually evasive and always inadequate. It gives me the strange feeling that I don’t understand myself well enough for a man in his mid-thirties. The feeling grows when I consider the irony that my posters aim to confront the Australian people’s collective lack of self-awareness. Maybe it’s time that I cast out the beam in my own eye and made sense of my motivations.

Since I started sticking up my posters I’ve had countless confrontations with people on the street. They’re almost always men, usually my dad’s age and often angry. I wish I could say I’ve always behaved fairly towards them, but I haven’t. I wish I could say I’ve never taunted these men and inflamed their insecurities, but I often have. Because men like that always have personal inadequacies hidden beneath the veil of their political convictions. I know this because I’m really no better than they are. I feel that I owe them an apology, or at least some acknowledgement that we’re not so different.

The other group of people with whom my interactions follow a troubling pattern are the young political activists. These types have usually dedicated a whole semester to swallowing whatever worldview best weaponises their angst, before setting out to fix the world. Like budding Raskolnikovs, they’re irritatingly intelligent. They hate my posters for their appeal to the political centre. They hate the ironies that seep between the cracks in their convictions. Like the puritans of old, they ultimately hate their own imperfectibility. I honestly admire their enthusiasm but it’s a terrible thing to have a chip on a young shoulder. I should know.

Australia also has a chip on its shoulder. I’ve seen it everywhere I go with my posters. We hide it beneath our ‘she’ll be right’ larrikinism and Anzac Day pageantry, while our true identity is deep and dark and personal. For the last 200 years Australia has been playing the role of Western civilisation’s fun-loving sidekick. We like to see ourselves as the friendly underdog with heart. We lack the courage to take full responsibility for our history because our national psyche is adolescent. We won’t admit that we traded innocence for power a long time ago. But our immaturity isn’t entirely our fault; it’s also due to a spiritual poverty that’s afflicting the Western world at large.

I chose to be an artist rather than follow my training in psychology because art is really a spiritual project. Since the Enlightenment, art has become the Western world’s attempt to remedy its spiritual disenchantment, especially during the twentieth century. The Cubists initiated a cult of abstraction while the Surrealists sought to replace God with the subconscious. The Dadaists, ahead of the game, answered the death-of-God by exulting in the absurd. One by one, every Modern Art movement collapsed under the weight of its own pomposity and the squeeze of free-market nihilism. Today we view art history through the lens of the market. As a result, we see only a succession of novelties rather than a battle of ideas. Many of today’s artists have embraced the market’s hunger for sheer novelty. Others have learnt to mimic the academic jargon of the curatorial clergy who run the state-sponsored art institutions and offer refuge to artists who mutter the correct incantations. Increasingly those mutterings favour ideology over aesthetic or spiritual aspirations. My posters are also a symptom of this trend. Without spiritual aspiration, political art is little more than a visual commentary on power. Artists like me have forgotten how to adapt and renew our most powerful unifying myths. It’s no surprise that tribalism and stale ideology keep moving in to fill the vacuum.

This might all seem a little grim and abstract, so I’ll try to bring it back home. I can describe my own spiritual poverty with a simple phrase: my struggle to ‘become a man’. Of course the phrase is uncomfortably anachronistic, just like the phrase ‘Real Australian’. It’s a phrase that attracts suspicion, like a dog whistle to toxic tradition or a roadblock to the genderless utopia that forever waits beyond the horizon. But the type of manhood that interests me is about responsibility, not entitlement. In this sense, my art is a personal attempt to reform my own sense of manhood, by attempting to reform our collective sense of nationhood.

Just as Australia’s psyche is adolescent, I too feel more like a boy than a man. I’d like to fix that. In this book I’m going to explore my strange journey to becoming a poster boy of hashtag activism. I’m going to be open about the personal shortcomings that motivated my projects. I’m going to be open about my mistakes, public and private. I’m going to be open about everything I’ve learnt from the people who have tried to stop me, and those who have helped. I’m going to tell you all this because it’s what I need to do in order to grow. After thirty-five years, I’m tired of being a boy who lives in a childish country.

![]()

Ambition and Apologies

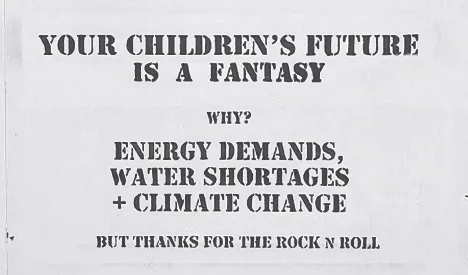

I made this stencil in October 2009. I’m not particularly proud of it. In fact, I find it pretty embarrassing, but I think it’s worth showing you because it reveals something about me that still hasn’t changed. It’s also the first piece of street art I ever made.

I grew up in a household where no one ever apologised and no one was ever forgiven. I know that sounds a little dramatic but it’s really not much of an exaggeration. It’s taken me a long time to learn how to apologise and I’m still not very good at it. If you don’t believe me, just ask my wife. Whenever we have an argument I turn into a Rubik’s cube made of stone, only less emotional.

The atmosphere at home cycled between dormant, snarky and explosive. The root cause was definitely my parents’ relationship. I’ve never witnessed an act of physical affection between them. Sometimes they bicker in an affectionate way but I’ve never seen them exchange a simple kiss or a hug. I didn’t realise that my parents’ relationship was unusual until I was twenty-one. I distinctly remember being at a friend’s house and seeing my friend’s parents casually give each other a kiss. I thought, What the fuck was that? I asked my friend about it and he looked at me like I was weird. Then it occurred to me that maybe I was weird. The exact reason for my parents’ estrangement had always been a mystery, although I can’t say I spent much time wondering about it. That’s just the way it was.

Despite our family’s lack of affection there was never any lack of ambition. In fact, there was so much emphasis placed upon achievement that I wondered whether one compensated for the other. When it came to encouraging good grades, my dad had a simple system: he gave me $20 every time I got an A. So I got straight As. I was making $120 every term and it was easy money. I wasn’t particularly smart, I just didn’t socialise. That’s how I graduated from high school with an excellent Tertiary Entrance Rank and the social skills of a shut-in. I was perfectly qualified to follow my half-baked dream of becoming an accountant. The University of Adelaide offered me a position to study Commerce at its prestigious business school and my parents couldn’t have been happier. Then, in the summer between school and uni, I discovered friends, drugs and girls. I dropped out of uni within a month.

Throughout that period I was quite happy to be a fuck-up. Subconsciously I’d realised that my parents’ love was conditional upon my achievements, so I felt a perverse sense of righteousness in squandering my own potential. However, my cynicism wasn’t reserved for my parents. I’d decided that the whole world was faulty and I was going to escape it by constantly getting high. My new lifestyle didn’t sit well with my family, especially since I was still living at home. At one point the tension spilled over into violence. I was arguing with Dad when a fight broke out between me and my older brother, Julian. My younger brother, Simon, jumped in to help me. Then Dad jumped on Simon. For a moment there were four grown men brawling in the hallway. It’s funny to remember but it was bloody awful at the time. Afterwards my dad and I were both in tears and he told me that he loved me. That’s when I knew I had to get my shit together.

Reluctantly, I enrolled in a course of Psychology and Philosophy. I wasn’t interested in a career in either discipline but I did have a strong desire to understand the world. Really, I wanted to understand myself. During the course I gravitated towards art. I wasn’t particularly talented, I just felt like I had something to say. And that’s how I became an artist. I moved into a share house, fell in love and got married.

I was a painter before I got into street art. I painted large, colourful canvases that bear little resemblance to the art in this book. In 2008 I was offered my first solo exhibition at a small commercial gallery in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs. The gallery owner believed my work was saleable, but that was before the global financial crisis. When my exhibition finally opened a year later, the art market had collapsed. I only sold a few paintings. The owner of the gallery said I was lucky to have sold anything.

I took my unsold paintings back to my studio. Before the exhibition I was actually scared to sell them, but now I was afraid I’d never get rid of them. I stacked them in the corner of my studio and covered them with a sheet, but I couldn’t ignore them. Every time I sat down to paint new work, there they were, mocking my ambition. I began to wonder whether I should quit.

I’m not sure ‘ambition’ is the right word for the way I feel about art. When you’re a kid you don’t have ambition; you have a ‘dream’. We dream of growing up and doing something good, because we’re encouraged to believe that the world is good. We’re encouraged to believe that there’s a place waiting for us in the world. For me, ever since crossing the threshold into adulthood I’ve had the nagging feeling that the world wasn’t worth taking seriously. That I didn’t really want to participate. I was happy to observe life from the outside, but becoming a part of the world wasn’t for me. I didn’t know where that feeling came from but I believed that art was my best hope for fighting a way out of it.

So I really couldn’t quit. I needed to keep making art but I had to find some form of expression that didn’t rely on the disposable income of art collectors. It just so happened that my housemate was a street artist. At night he would go out to paint walls in the city. I kept asking him questions about how he did it, so one night he offered to take me out and show me the ropes. It was exactly what I needed. When you’re sneaking around the city at night you feel like a kid again. The seriousness of the world is unmasked as a series of façades, dead objects just waiting to be painted. I was immediately hooked. Out on the street I could say anything I wanted. So what did I want to say?

The idea for my first stencil came to me one night while painting in my studio. I was listening to the pithy pessimism of Radio National’s ‘Late Night Live’. Phillip Adams’ guest was predicting a future of terminal decline but instead of being worried, I felt emboldened. Alone in my studio, I listened intently, nurturing my wounded sense of entitlement as I designed my stencil on the computer my parents had bought for me. I used an old projector I’d stolen from the University of Adelaide to transfer the design to a large piece of cardboard. With a $2 Stanley knife, I cut out each letter. From beginning to end it took less than an hour. Finally, I picked up my $3 can of black spray-paint and headed out into the night. I was ready to deploy my 26-year-old wisdom. I was ready to become a street artist. I kept painting and holding exhibitions for another two years, but it was only a matter of time before street art took over my life.

Twenty-six is pretty late to begin a career in vandalism. While many graffiti artists are hanging up their spurs at that age, I was just getting started. Since then I’ve become both better and worse. My posters have become more optimistic but there’s still something aggressive and arrogant in the way I stick them up on other people’s property. I can offer various intellectual arguments for my behaviour but the real reason is temperamental. Part of me would rather be in the position of owing an apology than asking for approval. After almost ten years of making street art, that still hasn’t changed.

![]()

Finding Out

My life began to make more s...