![]()

I

Swamp Gas Journal

Long associated with fairies, swamp gas has been blamed for luring travelers into the wilderness, where they get lost and never return. The Chitimacha tribe enjoyed the first glimmer of human life in the Atchafalaya Swamp, leaving little evidence beyond dots on old maps. Then the Bayou Chene community flourished for about 150 years, leaving behind census records and blurry photos in family albums. I was part of the last community there in the 1970s. No one lives out there now, but perhaps someday humans will again call the Atchafalaya home. In the meantime, C. C. Lockwood’s photos and my journal will preserve our little flicker of swamp gas for generations to come.

![]()

1 The Decision

Raccoon feet tickety-tacked out of the back room when Calvin and I entered through the hole where the front door used to be. The guilty flick of a retreating snake’s tail seemed to say, “Pardon me, I didn’t think you’d be coming back” as it slipped down a crack in the six-inch layer of dried gunk covering the kitchen floor. By July the weight of that mud had broken the boards and pulled them away from the walls, finishing the demolition job started by the floodwaters of February. As depressing as my last view of our home had been—with its roof poking bravely above the brown swirl of overflow from the Atchafalaya River—it couldn’t compare with the desolation I felt seeing the aftermath.

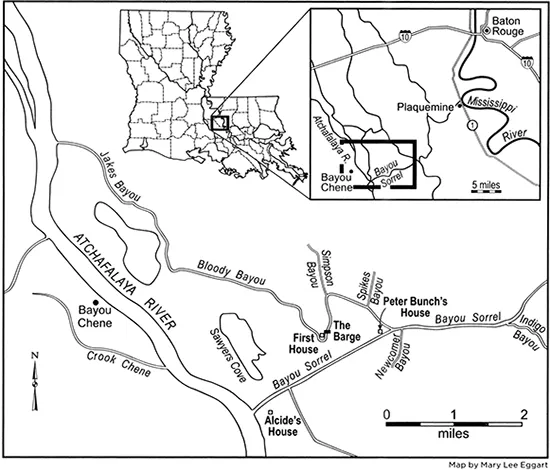

The high water shouldn’t have been unexpected. Our home had been nestled deep in the Atchafalaya River Basin Swamp—1.4 million acres of wilderness designated a floodway by the Army Corps of Engineers shortly after the devastating flood of 1927 destroyed settlements along the Mississippi River. By the early 1930s, locks were in place at the junction of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya rivers above Simmesport, Louisiana, and retaining levees stretched along each side of the Atchafalaya to its mouth in the Gulf of Mexico. From that time on, the dangerous bulk of the Mississippi’s spring rise could be diverted away from the cities by pouring it into the spillway, or Spillway, as the Atchafalaya Basin came to be called by sportsmen. The river itself, with the melodious Chitimacha Indian name, now was referred to simply as the Channel. By changing its function, the identity of the great swamp also had been altered.

For eons the Atchafalaya Swamp had been cut off from the rest of the world by the river and its bayous. It was too wild and forbidding for most people, but there were a few people who loved it for its very isolation. For them the rich soil, plentiful fish and game, abundant furbearers and virgin cypress timber were actually secondary in importance to the precious solitude.

Our families were in that group of ornery and independent folk who left civilization to build their own schools, churches, stores, houses, and even a post office in the dense, green swamp. By the time the Army Corps of Engineers began its epic, earth-moving, channel-changing project, Bayou Chene was more than one hundred years old and right smack in the middle of the proposed spillway.

Even with their ancestral home designated a floodway, the idea of living “outside” was so distasteful to the swampers that most of them tried to stay. When the floodgates were completed and put in use, the people of Bayou Chene modified their life-styles to accommodate the water. They raised the floors in their houses and built wooden rafts to stable their cattle for months at a time.

Eventually, though, they began to acknowledge the futility of fighting the annual war against water. Each flood season a few more residents fled to the levees and never returned to clean out their water logged homes. Outboard motors appeared just in time to help the people of Bayou Chene ease into life on the outside. A swamper could establish his family and livestock in settlements outside the spillway yet continue making his traditional living by fishing, frogging, moss picking, timbering, and trapping.

During the 1940s and 1950s, the old community gradually disappeared as buildings were torn down and rebuilt outside the floodway. Only camp boats or rough shelters remained inside the swamp as bachelors’ quarters for the times when fishermen or trappers had to stay overnight.

That sort of compromise lifestyle, however, was too bland for Calvin Voisin. As a child growing up in the levee community of Bayou Sorrel and learning from his grandpa George Ray how to set lines and nets, he dreamed of not only earning his living from the swamp but also staying full time among the silver cypress and whispering cottonwoods. He would talk about it during the summers I spent with Maw Maw Josephine and my aunts. Sitting in her swing on a hot afternoon or waiting for church to start three times a week at the Bayou Sorrel Baptist Church, our conversations usually ended up in the Basin. The conversations stopped when I started college and Maw Maw moved to Baton Rouge.

After he graduated from high school and couldn’t remember a spring flood ever coming over the bank, Calvin moved a vacant house from Bayou Sorrel about ten miles into the swamp where Bloody Bayou made a bend to converge with Jakes Bayou. He enlisted the help of some friends to put the house on skids and load it onto a barge. Another friend who piloted a small towboat pushed it out there during high water. It was history reversing itself, as the grandparents of these very kids had helped each other move from Bayou Chene to the levee decades ago. Once skidded into place the old house commanded a stunning view of both bayous from its vantage point in the bend, which the boys nicknamed La Point.

La Point was within earshot of where Calvin’s grandmother had lived as a child and walking distance of where she later started her own family on Simpson Bayou. But by that time—the early 1970s—there was no sign that humans had ever lived around there. Not a dishpan left in the weeds nor a hoe handle sticking up out of the sand.

Oh, there were stories. Old-timers recalled that Bloody Bayou got its name the night a man was killed at a saloon on its bank. No one knew the stranger’s name, but his blood became part of the Basin’s cartographical history. Another story was told about a grandmother rocking a baby on the deck of a houseboat one sunny afternoon while the parents were out gathering moss. She didn’t notice that the rocking movement of the chair was inching backward until she and the baby flipped into the water. After several minutes she managed to haul herself back up onto the houseboat, but by that time there was no sign of the baby. Like so many Bayou Chene residents, she didn’t know how to swim, so even if he popped to the surface she wouldn’t have been able to save him. With no boat and no neighbors within shouting distance, she could only pace the deck and wail her distress. Fortunately, her agony was short lived, as she soon heard the put-put of a motor coming around the bend. A fisherman had found the baby downstream floating on the air trapped under his billowy gown.

Such stories were all that remained of the old civilization when Calvin completed the move in June 1972. I had just finished my master’s degree and was looking for an unusual summer job before starting Ph.D. work in September when we crossed paths at a family funeral. His wild hair was bleached almost white from the sun. Lines were already etching around blue eyes that glowed when he described what the Basin was like on the inside. I had to see it for myself; he took me on as a fishing partner.

That summer turned into an education as I learned how to drive a boat, how to set nets for catfish, and why some people choose outdoor occupations. I became acquainted with my body, which had been ignored for years as just locomotion for my brain. It awakened from sanitary, air-conditioned hibernation to the trickle of sweat down my arms, the green fragrance of crushed cypress needles, and the sensuous luxury of a bath with Ivory soap (because it floats) in the bayou at sunset.

As my body grew brown and hard, muscles I didn’t know I had ached to tell me of their existence. Food tasted better than it ever had in my life, but at the end of the summer I had to tie my jeans with fishing line or risk losing them. In school, I had often watched midnight come and go, but now it was difficult to stay awake an hour past sundown. My mind observed and recorded these changes with interest.

I became so absorbed in mastering the not-so-simple skills of the simple life that September came and went unnoticed as I tried my hand at cutting wood, canning vegetables, preparing a smokehouse, and making a quilt. Every day there was something new I wanted to learn. Old swampers told me about moss mattresses, wild berry wine, cypress shingles, and hogshead cheese. There wasn’t a graduate program in the country that could have enticed me away from my wilderness home. I was too busy continuing my education to make time for school.

We drifted through that year in a daze of enthusiasm. We painted, patched, and hung curtains in the old house. Vegetables and roses sprang out of the black earth, encouraging us to put in an herb garden and small orchard. The fish and game that had attracted the first swampers were still plentiful. We wondered how those old timers ever left this paradise for the stark, unlovely settlements perched along the levees. Then the flood of 1973 answered that question with a vengeance.

In early January when the locks started diverting the Mississippi River into the Atchafalaya, we knew it was going to be a high-water year. Well, that would be good for fishing. But the water kept coming. Our neighbor Mr. Richard Bunch stayed abreast of weather and water news through his CB radio. We’d listen to the predictions during our daily visits with him and then watch, twelve hours later, as the cold water inched up the precise amount foretold.

The climb up the twenty-foot bank from our boat kept shrinking until, finally, it was a level step out to the landing. One day a brown curl began seeping over the edge toward the garden where we had planted snap beans on Valentine’s Day. That was when we started wearing rubber boots every day. Then we brought the garden tools into the house. One morning we spotted a snake hanging from some exposed rafters over the breakfast table, so we started checking under the pillows before we went to bed at night. We moved Calvin’s paint horse and a Shetland pony to the highest ground we could find, but a few weeks later we had to take them by raft into Bayou Sorrel. Finally one bright February day, we loaded everything that would fit into our bateau and left.

Touring our water-wrecked home six months later, I idly pried relics of our life from the mud while contemplating the dreary prospect of returning to life in civilization. A jar of preserved pumpkin winked like hot coals in the July sun. I recalled the October afternoon we peeled and chopped them on a wooden block under the cottonwood tree just a few feet from where we had harvested them. Cooked down thick with sugar and cinnamon, they had gleamed in the lamp light on my kitchen windowsill later that night. Now I wondered if they were still edible after being submerged. The Ball Blue Book of Canning and Preserving didn’t cover that situation.

I kicked against a lump of hardened clay and sand. It shattered to reveal my grandmother’s china soap dish, miraculously unbroken. The toe of my shoe turned up a muffin pan filled with twelve perfect mud cupcakes. I realized with what heartbreak my ancestors had given up the battle.

Calvin broke into my thoughts as if he had been eavesdropping.

“Instead of fighting the water, maybe we could cooperate with it. What do you think about houseboats?”

“Not much,” I replied, picturing the tiny, dark one-roomers usually equipped with a single cot and a camping stove used by sportsmen. Floating on empty oil drums or homemade pontoons, they served well enough for a weekend shelter but wouldn’t inspire homing instincts in a pigeon. Calvin charged ahead.

“I mean a big house, built on one of the steel barges that the riverboats push—a full-sized home with a brick fireplace and lots of windows. It would let us rise and fall with the water level all year.”

It was a wild idea, but we certainly had nothing to lose. Even our lack of money to buy a barge wasn’t a drawback, because we weren’t likely to find one for sale. Nevertheless, the word was put out to old friends, casual acquaintances, and complete strangers that we were shopping for a barge. We also mentioned we were looking for an old cypress house to recycle. Having placed our order, we separated to earn money.

![]()

2 Earning Money

Calvin had worked with surveyors in the past, so he started traveling the country with a crew that cut right-of-way trails. Swinging a chain saw or a brush hook all day kept him in shape and paid decent wages.

I continued my education with on-the-job trainings. A friend of mine was going to Pennsylvania for graduate school, and I was anxious to sample odd jobs in another state, so I tagged alone. Once there, I stumbled upon a kennel of show whippets needing a manager. Not knowing a whippet from a wolfhound, I got the job anyway because not many people were vying for the position, which required living with eighty whippets in an old mansion on holiday from the pages of a gothic novel. The owners were always on the show circuit or in Europe.

The first thing I learned on my new job was that owners of old mansions don’t bother to heat the upper floors where the help sleeps. The second thing I learned was that whippets make great bed warmers. Starting with two, I added seven more as the winter wore on. Let the snows fall, I still had 71 whippets in reserve!

As I went about my whippet chores, I learned about nutrition, diseases, and genetics. And it wasn’t all manure and worm pills; the glamour and aggressiveness of the show world became as familiar as blackboards and chalk. I spent my time with teachers I wouldn’t have met in college—grooms, gardeners, trainers, and vets.

It was the kennel vet who told me that Philadelphia’s Academy of Natural Sciences, the oldest museum on the continent, needed someone to care for animals and give educational talks for students on field trips. The opportunity was too intriguing to pass up so I bid seventy-nine of the whippets good-bye. Lemon Peel was foisted on me by her owners, who had noticed she welded herself to my foot the day I arrived. Lemon had been spayed the previous summer because of complications with her first litter of pups. She was now of no value and probably would be destroyed in the next culling. She seemed to sense I wouldn’t be staying and clung to me as her ticket out. Early one Sunday morning with the housekeeper and about fifteen whippet tails waving good-bye, she didn’t look back as we pulled out of the driveway of the only home she’d ever had.

At the Academy I fed, medicated, cleaned, exercised, and entertained 150 assorted animals. Every day brought new opportunities to be awestruck. I stroked a great-horned owl and marveled at how those silky feathers could propel him with deadly silence. Carefully petting a porcupine, I could examine for myself the low-tech genius of her protection system. With the weight of a thirty-five-pound anaconda draped around my neck and lying on top of my outstretched arms, I could feel what it was like to have great strength but no limbs. It was a hoot to be learning about nature in the fourth-largest city in the nation. Most important for my future, I was responsible for translating the scientific information I was learning into language school children could understand. I found I had a knack for taking people, as well as one whippet, to places they might not go on their own. It was the beginning of my life as a writer.

I arranged to have Mondays as my day off so Lem and I could enjoy free admission to Philadelphia’s museums. We walked for miles on our excursions. The only blight on our outings came from street people who made fun of her unusual looks, which were topped off with a turtleneck sweater and plaid coat. Show whippets raised in heated kennels don’t grow the plush coats they had when the breed was first developed by English peasants. When people on the street...