![]()

PART ONE

African Resistance in Colonial America

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Fires of Discontent, Echoes of Africa

The 1712 New York City Revolt

From Dutch New Netherland to British New York

The history of forced labor in New Netherland began in 1625 when a Dutch warship unloaded a cargo of Africans plundered from a Portuguese vessel on the Atlantic. Similar circumstances just six years earlier had brought the first Africans to British North America. In 1619, another Dutch warship captured the São João Batista, a Portuguese vessel heading to Vera Cruz, and its cargo of about twenty Africans. This group of West-central Africans were disembarked, in exchange for food and supplies, to become the first African laborers to arrive in Jamestown, Virginia. The status of the first Africans brought to both Dutch and British North America was not clearly defined initially, and for at least a few decades there existed a number of avenues forced laborers could use to obtain freedom. The idea of permanent and racialized slavery did not develop in either region until the mid-1660s. These Africans inhabited a nebulous social space between indentured servitude and slavery. Initially it seemed that they would have the same opportunities as European servants and would, perhaps, share the fruits and rewards the New World offered. To borrow the words of Peter Wood, the “terrible transformation” that led to the eventual development and proliferation of race-defined slavery during the second half of the seventeenth century helped determine the poisonous race relations that have manifested throughout much of North American history.1

New Netherland was established primarily as a fur trading post by the Dutch West India Company, and the colony and its Dutch settlers struggled during the early-seventeenth century to find sufficient sources of revenue and labor. Concentrating most of their efforts on major territorial claims in West Africa and the Caribbean—Gorée and Curaçao respectively—the company’s directors had little interest in investing the significant amount of capital necessary to make New Netherland a successful settler colony. As a result, the Dutch West India Company proposed two separate plans to solve the economic problems faced by their North American colony. The first solution was the establishment of patroonships, or landed estates granted to the wealthy. Patroonships, much like the headrights the Virginia Company bestowed in the Chesapeake, were incentives meant to encourage immigration to America. Wealthy Dutch settlers receiving landed estates under this system had the responsibility of attracting and paying the necessary transportation costs for up to fifty new settlers each. Only one patroonship was established during the entire period of Dutch rule in New Netherland. The company’s second, and most successful, plan was the importation of Africans to be used primarily as agricultural laborers and as workers in the construction of public buildings and military fortifications.2

The names of some of the first Africans imported into New Netherland—Paul d’Angola, Simon Congo, and Anthony Portuguese—clearly denote their origin in West-central Africa. In the early 1570s, Portugal conquered Angola and established peaceful commercial relations with the nearby Kongo kingdom. West-central Africa would be an early source of labor for the Portuguese colony of Brazil and, due to the actions of Dutch warships and privateers on the Atlantic, both British Virginia and Dutch New Netherland would import a number of Africans from this region as well. When the Dutch West India Company was first chartered in 1621, it began an aggressive campaign against Portuguese claims in Atlantic Africa and the Americas in an attempt to undermine the Portuguese trade monopoly and to acquire Africans by more direct means. The company captured portions of Brazil by 1637 and moved to wrest control of a number possessions in Africa away from its Portuguese rivals.3

In an attempt to fulfill their public promise to “use their endeavors to supply the colonists with as many Blacks as they conveniently can,” the company sought to become the primary conduit for Africans entering Dutch American colonies.4 Between 1637 and 1647 alone, the Dutch West India Company claimed the Portuguese possessions of El Mina, Príncipe, Angola, and São Tomé through military conquest. Even though the Dutch could only manage to control Angola from 1641 to 1648, they had effectively replaced the Portuguese as the dominant European power in Atlantic Africa by the mid-1640s. This complex web of interconnections within the Atlantic World, fostered by trade, international rivalry, and war, became an essential component in the development of a number of Euro-American societies.5

By 1627, a total of fourteen Africans had arrived in Dutch New Netherland, but this initially slow trickle became a torrent over the course of the next half century. The absence of cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, or rice did not slow the need for African labor in Dutch North America. The Dutch West India Company helped fuel further demand, noting in a 1629 report to the States-General of the United Netherlands that the colonists “being unaccustomed to so hot a climate can with great difficulty betake themselves to agriculture,” a feat made even more arduous by the fact that they were “unprovided with slaves and not used to the employment of them …”6 This situation would soon change, and the importation of Africans became the company’s principal focus with the arrival of the first slave ship in 1635.

In 1644, the Dutch Board of Accounts advised that for the purposes of cultivating land and growing wheat on Manhattan Island, “it would not be unwise to allow, at the request of the Patroons, Colonists and other farmers the introduction from Brazil, there, of as many Negroes as they would be disposed to pay for at a fair price.”7 This request was followed by the arrival, two years later, of the second recorded slave ship in New Netherland, the Amandare. Because it directly controlled large portions of Brazil between 1637 and 1654, the company was able to create a unique trade relationship between New Netherland and Brazil. In a trade arrangement drafted in 1648, the colonists in New Netherland agreed to ship fish, flour and produce to Brazil in exchange for as many African laborers as they required. Within four years of the establishment of the Brazil–New Netherland commercial agreement, direct trade with West Africa for slaves was opened and a slight reorientation of the slave trade began. In prior decades, the Dutch were satisfied with plundering Portuguese slave ships or procuring African laborers from Brazil or Spanish America. As a result, the majority of Africans entering New Netherland were from Loango and other West-central African regions.8 One contemporary source notes that Africans entering New Amsterdam in the decade after 1625 were “Angola slaves, thievish, lazy, and useless trash.”9 Despite this negative characterization, enslaved “Angolans” or West-central Africans would prove essential to the economic viability of the colony during its early years.

By allowing Africans to be directly imported into North America via Dutch West India Company–owned or commissioned ships, New Netherland soon began to receive a number of Gold Coast Akan-speakers exported from Dutch-controlled trading factories in West Africa to supplement the West-central African imports. After capturing El Mina Castle from the Portuguese in August 1637, the Dutch controlled the most important slave trading factory along the Gold Coast until its transfer to the British in 1872 (see fig. 1.1). The immediate result of the capture of El Mina was the importation of Gold Coast Africans into Dutch American colonies. The 1659 charter for the ship Eyckenboom allowed the captain of this vessel to trade at El Mina Castle and “from thence proceed further to the islands of Curaçao, Bonaire, and Aruba … and also to New Netherland.”10 This new source of African laborers became even more important after 1648 when the Portuguese managed to recapture their Angolan possessions from the Dutch, which effectively cut off a major source of West-central African imports. Also, with the Portuguese recapture of Brazil, the unique commercial arrangement between New Netherland and Brazil was brought to an abrupt halt.11 In New Amsterdam, and later New York City, this reorientation of the slave trade and the importation of Akan-speakers from the Gold Coast would have profound implications for the history of slavery and the development of African American culture in the region.12

FIGURE 1.1. El Mina Castle, ca. 2002. Photo by Walter Rucker.

The dominant position the Dutch enjoyed in Africa and the Americas came to an end in 1664. The Second Anglo-Dutch War of 1664–1667 helped create a major power shift throughout the Atlantic World. During the war, the English seized most of the Dutch claims along the Gold Coast, with the notable exception of El Mina Castle. The English also managed to capture New Netherland. Angered over repeated violations of the Navigation Acts of 1651 and 1660, the English crown decided that New Netherland was a significant obstacle to its economic interests in the Americas. By claiming the region, the English grabbed control of the contiguous territory from the Chesapeake to the New England colonies. Having already proven the military vulnerabilities of Dutch colonies during the First Anglo-Dutch War of 1652–1654, the English were able to peacefully capture New Netherland after a brief naval blockade. Peter Stuyvesant—director general of the Dutch West India Company and governor of New Netherland—capitulated on September 8, 1664, effectively ending four decades of control by the company over what would soon become New York.13

When the English appropriated this region under King Charles II, it was already one of the most culturally and ethnically diverse regions in seventeenth-century North America. When James, the Duke of York, assumed control of New Netherland and renamed the area New York, sizable populations of Dutch, English, French, Germans, Scandinavians, and at least 375 Africans from varying ethnic groups already lived on Manhattan Island. The Dutch West India Company’s incessant, and at times desperate, need for European settlers or African laborers had helped create a diverse and cosmopolitan society. The colony had been forced to accept settlers of various European nationalities out of sheer expediency; the comparatively high living standard in the Netherlands during the seventeenth century compelled the Dutch to stay in Europe. The failure of the Dutch West India Company to attract sufficient settlers led to its eventual bankruptcy and British control over its North American colonial possessions.14

The system the company established simply did not provide a strong enough incentive to lure the Dutch to North America in sufficient numbers and, according to historian Edgar McManus, “The prospect of living as feudal dependents of a great landlord had almost no appeal to the ruggedly independent Dutch.”15 The dearth of colonists during the early years of Dutch settlement in North America provided an obvious impetus for the continued importation of African labor. This reliance on Africans was epitomized by the arrival of the last Dutch West India Company commissioned ship—the Gideon—in New Amsterdam in the summer of 1664. The Gideon carried a cargo of 300 from Loango in West-central Africa, representing 80 percent of the African population residing in New Amsterdam, 6 percent of Manhattan’s total population, and 3 percent of the entire population of New Netherland. The Gideon was also the ship that loaded the remaining Dutch soldiers from Fort Amsterdam after the company capitulated to English rule in September 1664.16

Almost instantly, the English recognized slavery as a legal institution. The “Duke’s Laws,” passed a year after British rule was established, included provisions that allowed the practice of service for life. While the Dutch had never codified slavery, the experiences of the Dutch West India Company in Atlantic Africa and Brazil gave its proprietors a keen understanding of the concept, and some Africans were already serving lifelong labor contracts before 1664. According to Joyce Goodfriend, with English control came “a constellation of laws governing the lives of slaves” which “substantially restrict[ed] the latitude of black people in New York City.” The end of Dutch rule in Manhattan made slavery a very real and lasting concept for its African inhabitants. The opportunity for Africans to obtain their freedom, own land, or even have their own pool of dependent European or African laborers would be completely shut off by the eighteenth century.17

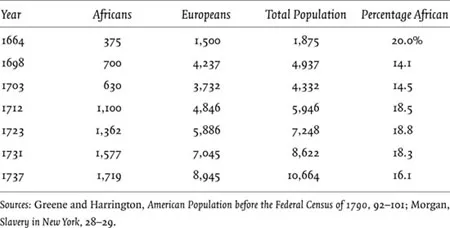

Africans made up roughly 20 percent of New York City’s population at the time of the British conquest (see table 1.1). The steady influx of labor from the Caribbean and Africa, initiated by the Dutch West India Company, would persist under British rule, especially after the Royal African Company was chartered in 1672. Though the Royal African Company concentrated primarily on the trade from West Africa to the Caribbean, they actively encouraged the reshipment trade in which private traders sold Caribbean slaves to New York and other North American colonies.18 In 1676, Sir John Werden noted that once the Royal African Company traded enslaved Africans from West Africa and “when they are once sold in Barbados, Jamaica, etc. by them or their factors, they care not whither they are transported from thence … and therefore you need not suspect the Company will oppose the introducing of black Slaves into New Yorke from any place (except from Guiny) if they were first sold in that place by the Royall Company or their agents.”19 In this manner, New Yorkers could guarantee as many enslaved Africans as they needed, and the population continued to swell unabated. By the 1730s, New York City had the largest African population of any colonial city north of Baltimore. In fact, it was second only to Charleston, South Carolina, as the city with the highest concentration of Africans in North America.

TABLE 1.1. New York City Population

Restrictive Eighteenth-Century Slave Laws

With the arrival of British rule in New Netherland in 1664 came a series of laws that helped define the parameters of slavery in what later became New York. The first British mainland colony to legalize slavery was Massachusetts, which did so in 1641. Slavery would eventually be legalized in all thirteen North American colonies. Because slavery existed in some form on Manhattan Island before the arrival of the British, the slave laws the new government created were merely reflections of an ongoing reality. The Duke’s Laws stipulated that “No Christian shall be kept in Bond-Slavery, except such who shall be judged thereto by Authority, or such as willingly have sold or shall sell themselves.” Consciously modeled after a comparable law in New England by a group of Puritan settlers residing in Long Island, the Duke’s Laws exempted any African professing Christianity. This loophole would soon be corrected. In 1674, the law would be amended to read “This law shall not set at liberty any Negro or Indian Slave, who shall have turned Christian after they had been bought by any person.” This new provision helped solidify the notion of perpetual racialized slavery in New York until the time of the American Revolution.20

The Act of 1706 further defined enslaved Africans and Native Americans in New York as inferior in status to English settlers. This act went against English Common Law, which stipulated that children would adopt the status of their fathers. Instead, the Act of 1706 mandated that “all and every Negro, Indian, Mulatto or Mustee shall foll...