![]()

1

A PLACE IN TIME

From the air, Marrakech seems to throb in the summer haze of the brown Haouz Plain like an agitated neuron, thin asphalt tendrils winding out from it. Oddly shaped turquoise splotches ring the better suburbs of the city: the swimming pools of the rich and fortified tourist resorts hemmed in by high walls, palm trees, bougainvillea, and armed guards. Thin sheep graze outside the walls in dirt lots strewn with wisps of plastic bags. The streets are wide here, smooth black asphalt quiet but for the few hours a day when the commuters leave and return, or when busloads of sunburned tourists rumble past on the way to their compounds. Other suburbs are less elegant: mile after mile of rickety cement-block apartments, with rows of stores on the ground floor.

Folded within these suburbs is the medina, the old city center. It remains the core of Marrakech, with imposing red walls erected a thousand years ago and the venerable Koutoubia minaret rising as a sad reminder of spent imperial glory. In the poorer quarters of the medina laundry dries on every rooftop, stirring like Buddhist prayer flags when a breeze wends through the city. Below the jumble of roofs, in the raucous streets of the old urban center, smoke-spewing buses jostle with bicycles and trucks, cars and horse-drawn cabs, donkey carts, pushcarts, pedestrians, and swarms of whining, careening, soot-belching mopeds. At its core Marrakech is a city alive, one of the fastest growing in Morocco, popular with tourists from Kansas to Korea who come seeking heat, sun, and a dose of exotic, “timeless” culture.

The city is particularly popular with Europeans, and an international airport pipes great floods of them in for holidays. The rich retreat to their fortresses while the middle class sprawls into the streets to gorge on the cheap wares produced for them: carpets, scarves, brass bowls, pottery, T-shirts, turbans, thuya wood carvings, lamps, argan oil, ancient doors (and doors weathered to look ancient), and pot after pot of sweet mint tea. Marrakech is professionally exotic now. Tourism is big business, and the stalls of the famous outdoor carnival at Djeema El Fna have been numbered, electrified, and aligned on a grid. Since the end of the French protectorate in 1956, the city’s estimated twenty-seven thousand colonial-era prostitutes have been dispersed or driven underground. The medina is now half living city and half folklore-for-sale, a slick and sometimes sad parody of itself. Marrakech remains alluring even in her dotage, however: a busy hive of humanity on a sweltering plain.

South of the city the massive Atlas Mountains stand silent against the sky. Snowcapped from November through July, the core of the range is anchored by a cluster of peaks over four thousand meters (thirteen thousand feet) high. Rivers of snowmelt plunge out of steep valleys, dissipating on their way down until they flow thinly on to the plains. To the north these waters slake Marrakech’s growing thirst for daily showers and swimming pools. To the south, what streams escape the mountains are captured in cement dams, or seep into rocky alluvial fans that lose themselves in the desert. Beyond the Atlas is the immense expanse of the Sahara, and beyond that the rest of Africa.

From the perspective of Marrakech, the Atlas Mountains stand as solemn, unfriendly guardians between the modern, civilized world—anchored by the city—and the great desert beyond. The mountains are a place of the past, where cultural practices survive not because they are for sale, but because people evidently cannot, or do not want to, escape, because people labor hard to reproduce themselves and their way of being. Many urbanites are recent migrants themselves, but the children and grandchildren of mountain people do not dwell on this past, do not usually romanticize it. Most urban young people think of the mountains as dirty, old-fashioned, ignorant, laborious, forgettable. This is perhaps changing as the government begins to promote (rather than repress) the Berber heritage of the nation, but the stereotypical picture of a mountain Berber is still a bumpkin.

Marrakech is a city of migrants, a city built of migrant labor that flows out of the mountains like the melting snow. Some migrants stay and become urban. Some are here to seek their fortune and return to their mountain homes. Some have only physically left the mountains—they remain socially ensconced in their rural households and are still working for and within those households. From the perspective of the people who retain their links to the highlands, the forbidding Atlas look very different. There are no generic peaks, valleys, or rivers, no categorical villages, but instead specific named places, routes to, from, and among them, and warm known people in those places that bring them to life. To mountain people the mountains are “home,” with all the particularity that such a word evokes. What might look traditional or old-fashioned or static in the flatlands can feel quite novel and even vibrant up in the thinner air; changes in the rural world are not easy to detect from without, and cannot be simply deduced from a television in a mud-walled house, or a cigarette wrapper in the dung by a shepherd’s hut. If Marrakech hovers luminous and exotic on the periphery of the Western imagination, the Atlas are an imaginary beyond, a periphery of a periphery, even from the perspective of many Moroccans. This is a hard land of Berber (rather than Arabic) speaking farmers and herders, of insular mud-walled villages clinging to hillsides above the life-sustaining water of the rivers.

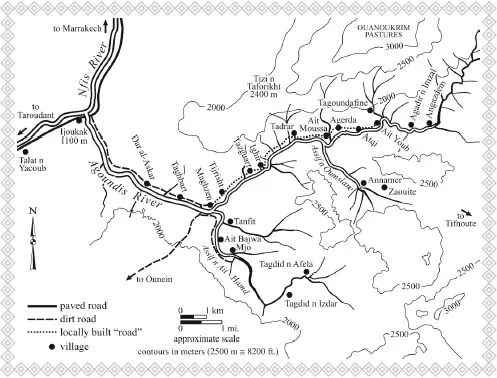

I first visited the village of Tadrar in 1995 while lost, wandering up the Agoundis River from the paved road at Ijoukak, searching for a Ph.D. dissertation topic and a place out of the heat. I had no map, no food, and no real plan. At that time there was no running water in the Agoundis, except for the river, no electricity, solar or otherwise, no toilets. Indeed, there was no road. The only way into the upper Agoundis Valley, and to Tadrar, was a series of narrow mule paths chiseled into the hillsides.

The Agoundis valley

From the main path, looking down, you would see massive walnut trees crowding the boulders of the riverbed. Fields of maize (in late summer) and barley (in spring) grow in carefully built terraces above the spring flood level. Almonds are planted throughout the fields and even higher, on ledges beyond irrigation where they grow thin and dry in hopes of rain. Rock and mud houses are terraced above the trees, clustered together in places that least frequently suffer rock slides. Grapes, pomegranates, figs, blackberries, squash, mint, potatoes, and tomatoes grow where space can be found in the dizzying patchwork of fields, trails, mud dams, and irrigation ditches. Olives, carob trees, and prickly pear cactus are scattered around the lower elevations. On the highest slopes above the village there are a few remaining Atlas cedar, some juniper and oak trees that the women use for firewood, and clumps of overeaten grass for the herds of goats and sheep. These public resources are ever scarcer, however, and are protected by sporadically enforced government laws.

The fields in the valley bottom are watered year-round by the ever-melting snow of the great Ouanoukrim Massif. Water is captured in temporary dams in the river that feed seven main targas, or canals, and many hundreds of minor channels and ditches. Each of these waterways has a particular name, as does each of the 1,411 fields of Tadrar, and so people are able to discuss space and movement through space at a level of detail sure to baffle any outsider. The targas are operated in rotation by the twenty-eight households of the village, and each canal has either a nine-day or ten-day cycle, with different households owning different sections of the days. Sometimes a wealthier household will own a whole day’s worth of irrigation water on a given canal, or even two days in a ten-day cycle. Poorer families can sometimes lay claim to no more than a few hours every ten days, and for them it is a long wait until they again have access to the precious water. The order of the rotations is decided by lottery at the beginning of the dry season, but the quantity of time is determined by inheritance, by the quantity of land owned.

The majority of the land in Tadrar is given over to grain, though some fields are too shady, especially those deep in the canyon beneath the walnut trees. These fields are used to grow tooga, fodder for the animals. The trails are too steep and narrow to drive the cows to the tooga, however, so the women bring the fodder to the cows. They cut it down near the riverbed until it runs out. When this is gone (as it is all winter long) women harvest bushes and shrubs from the mountains above the village and haul loads larger than themselves back to the lowing cows invisible in dark pens under the houses. The songs of the young women and girls echo through the valley as they carry fodder and water, collect wood for the bread ovens, or wash clothes, milk cows, and lug babies around in slings on their backs. Men and older boys work the irrigation system, plow, plant, and care for the sheep and goats in pastures both near and far. Younger boys mostly throw rocks at each other.

For those lucky enough to own flocks, there are more fertile, distant pastures, a day’s strenuous hike up at nearly three thousand meters above sea level, beneath the ridges of the Ouanoukrim Massif, a cluster of peaks at the center of what tourists know as the Jebel Toubkal National Park. These pastures are comparatively lush, but terribly cold and wind-swept. They can only be used during a few months of summer. The shepherds bring the animals down to their winter grazing area just above the village in October, before the heavy snows. Other less hardy animals, especially sheep, are kept in these local winter pastures year-round.

Partly because of the availability of these extensive pastures above the villages, partly because of the availability of water combined with the scarcity of flat land, this is one of the most densely populated areas of Morocco in terms of people per arable land unit (Bencherifa 1983, 274). In other words, these Berbers make more human bodies out of less dirt than almost anyone. This is part of the reason that the mountains function as a demographic pump—constantly generating surplus bodies that seep into the larger economy. Bodies are necessary for the intense labor needs of highland farming, but these bodies can only be built slowly, over time, and it is hard to plan well in a constantly changing world. Babies are insurance for the parents, but babies, too, must grow up and find a place in the crowded fields of the village. With a finite land base, there is always emigration. The intensive productivity of its mountain agro-pastoral system gives Tadrar a lush, Shangri-La feel: it is a dense thicket of green bursting from the crevasses of dry, impossibly rugged mountains. But it is a hard place, no paradise. There is little to sell, and thus no cash for doctors or dentists, books, paper, medicine, or, sometimes, even shoes. “Ishqa,” people said to me again and again, “toudert n’idrarn ishqa.” Life in the mountains is hard.

The body of Tadrar, the village itself, appears as a single mud and rock structure, a tumble of uneven blocks piled up the side of a steep ravine, or talat, that slices down the cliff face and empties into the river. Strewn with massive boulders and usually dry, this streambed plunges from a fracture in the rock wall above the village and falls through a progressively greener, thicker cover of walnuts, figs, and almonds. Tadrar is stacked up just outside the trees, above the irrigated terraces next to the talat. The village is a jumble of roofs and walls, a seemingly ad hoc set of straight lines that somehow form the right angles and odd rectangles that make buildings and indicate “home.” Some houses stand apart from the main village—solitary, squat, earthen structures with flat rooftop patios and small windows inset with metal screens and wooden shutters. But most of the village houses are wound together into a central knot that rises precipitously fifty meters above the road in a three-dimensional labyrinth of packed earth and precariously balanced rock. Invisible from outside the village, there is a cramped plaza open to the sky at the core of Tadrar, an assarag. Three dark passageways provide access to it, and go out from it on to the trails that lead to the surrounding animal pens, fields, orchards, storehouses, streams, and pastures.

On one side of the assarag, with a view out of the village over the road and river, is the mosque. It is indistinguishable from any other building. No plaque, special entrance, inscription, or directions tell you that this is the religious heart of the community. Inside the low door is a small antechamber: a bench runs along one wall along with an open window giving out on a view of the river; the wooden bier for the dead is propped in the corner. Just beyond this room is a long, narrow chamber with a series of taps running along the wall and another bench. Here the village men wash before praying and also do their more thorough bathing. The water is heated by a wood furnace invisible beyond the walls, or was until solar hot water was installed in 2004. Past this room is the actual mosque where men pray, a room empty but for reed mats on the floor, one high window, and a niche in the wall facing east.

The village is not set in two-dimensional space, and few visitors will be able to ignore what scholar Jacques Berque called the “audacious verticality” of the region (1955, 29). One never moves simply in or out from the village core, but always up or down, usually up and down along with much winding and turning. On the ground nothing is straight, nothing flat. Movement can be a general vector, but progress is a sensuously uneven route inscribed in the dirt, with a named destination at the end of it; destinations always involve travel past named places, around places and through them, and always moving up or down in addition to out or back. The paths unwind from the core of the buildings along the contours of the mountains like nerves to the extremities of the body. In one sense Tadrar, the mud and rock of the village, the physical structure itself, appears part of the land, a convoluted reconfiguration of the mountains themselves. But it is reconfigured. The ragged peaks seem to have been coaxed into recognizable order only in this one unusual spot. The stately, upright mien of the village states emphatically that here, within precisely built walls and perfectly smooth roofs, live people. Consistent angles and straight lines exist nowhere else in the mountains but for the tightly structured enclaves where people labor to set things straight. As in other areas of Morocco, the common word here for trustworthy, honest, or reliable is nishan, straight. To be nishan is to be—notably and in the best sense—human; it is to behave humanely.

This overview might give the reader some sense of how it feels to dwell in Tadrar, but is not, of course, how a villager comes to know her place. Imagine a baby born here. She enters the social world as she did the biological: through her mother. Babies come first to a small, dark room, maybe near the kitchen, certainly away from the door. From the world outside this room there are sounds—lowing cattle, chickens clucking, barking dogs, a crackling radio, the gentle rhythm of the call to prayer. Babies are born in the darkness on the carpets they will live on for years to come, blankets hand woven by mothers and grandmothers from wool sheared from sheep raised on the mountainsides above them, blankets that growing children will sleep under, fold, wash, stack, and shake out for themselves or guests countless times. But at first the world will be dark, the window, if there is one, shuttered. Neighbors and family visit, voices in the gloom. There will be eating and talking, the smell of mint tea and henna, wood smoke, women’s sweat, warm bread and boiled eggs, women’s voices mostly, and whispered prayers rolling from individuals and small clusters of the pious, submitting themselves to the will of God in the lambent poetry destined to form the soundtrack of every major life transition to come. As the week progresses more light is let in, and after seven days, if the child has survived, groups of women will come with gifts of food or firewood and the new villager will receive a name. Blessings given, blessings received, the new baby will be strapped with a shawl to her mother’s back and venture out from the room where she entered this world. The mother returns to work, and the child comes to sense the places that matter to women’s work.

Preeminent among these is the kitchen, the anwal. These exist in all sorts of formations, but most are simply an empty room with two or more conical ovens built into the floor, the tikatin (singular, takat)—the hearth of the home. It is constructed of mud packed around a specially designed clay pot, set upright and scored such that one longitudinal section can be taken out. Daily fires harden the mud to what feels like concrete. The slit up one side allows for kindling the fire and adding wood. They are open on the top, where pots of soup may be set to boil. Takat means “oven,” “hearth,” and also “household.” This hearth is the heart of the home, the primordial origin of all new villagers. Here, warm against mother’s back, eyes closed against the acrid smoke, babies are bathed in the scent of women, spiced coffee, boiling barley, and bread baking slowly in the ovens.

Most families eat on the roof in summer, or in an open terrace called a hneet, where they gather around the tajine. Tajine is the word for the peaked clay pots in which meals are simmered, and the word for the meals themselves. Cooked over coals scooped out of the takat and placed in a brazier, the tajine is filled with vegetables, a little oil, maybe some pepper or cumin, maybe a small piece of meat. It is placed on a low, round table, around which everyone sits on the floor. New babies suckle while mothers eat, or make many trips back and forth from the kitchen to the table with mother if there are no younger boys and girls to fetch the food. The patriarch (usually) reaches into a straw basket covered by a cloth and tears the rough, bowl-shaped tanoort, the bread distinctive to this region, into pieces. He scatters them around the table and announces the beginning of the meal with the name of God. Each person repeats bismillah before his or her first move to eat. The lid is removed from the tajine, and people tear their scraps of tanoort into smaller, bite-sized pieces, then dip them in the oil and vegetables of the tajine, and savor what the grace of God and the labor of women have delivered.

If there is meat, it is removed and placed in the lid until everyone is finished. Anyone who stops is encouraged to continue, and the conversation around the table is continually punctuated by the command, shta, eat. You draw only from the section of the dish in front of you, and to be polite you might press particularly delicious bits away from your section into a neighbor’s, who, usually, will subtly flick them back. When everyone is done, or almost done, the patriarch divides the meat, rarely more than a bite per person and usually not even that. In lean times there may be no vegetables or meat, but there is always bread. Bread is provided by God through the fertility of the fields or, failing that, by God through the properly Muslim generosity of more fortunate family and neighbors. Nobody goes hungry.

After dinner the table and the tajine are removed, uneaten tanoort goes back in the basket and is taken to the cows or chickens, and someone young brings around a kettle of warm water and a bowl to wash in. Then there is the extended ceremony of drinking tea, and while the young clean up, the older people rise to get back to work. There is no local category of “work,” however, except for relatively rare paid labor. Carrying babies, preparing food, tilling fields, threshing barley: these have their own verbs, but in general people are “making,” “doing,” or “busying” themselves. People are always busy, always doing, but they do not necessarily think of it as “work.”1

The fields are terraced up the steep mountainsides and strung together with a dense arterial network of canals and ditches that must be constantly maintained. As the river bites steadily into the bottom of the valley, scratching incrementally deeper into the history of the mountains, back in time, men struggle upward, pushing against gravity, against time, hoisting stone, moving rock, carrying dirt, transporting the animal dung that will render the land productive, that will allow the women to harvest the grain comprising the subsistence economy of the mountains—an economic mode coupled to a set of values (Michel 1997, 3). Every field has been wrenched from the mountainside, constructed and reconstructed, repaired, watered, and cared for by a long series of nameable persons. Each field has come into existence through human labor and survives (and remains fertile) only through continuous, coordinated work. This is the most “constructed” rural landscape in all of North Africa (Berque 1955, 24), and the construction is entirely accomplished through the sweat of humans and their animals.

Each field has a name and a history. The egran n tamghart, or “fields of a woman,” were a set of plots a long-dead father graciously gave to his son so the son could marry; the egr n akshoodn, or field of wood, was passed between families one particularly cold winter when “the snow was above our hips” and a man traded it for firewood. Sometimes fields are spoken of as families, such that a small field next to a larger one will be known as “the son of ”...