- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

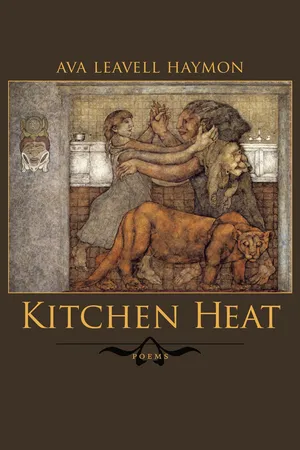

Kitchen Heat records in woman's language the charm and bite of domestic life. Ava Leavell Haymon's poems form a collection of Household Tales, unswerving and unsentimental, serving up the strenuous intimacies, children, meals, pets, roused memories, outrages, and solaces of marriage and family. Some of the poems are comic, such as "Conjugal Love Poem, " about a wife who resists giving her husband the pity he seeks when complaining about a cold. Others find myth and fairy tale lived out in contemporary setting, with ironic result. Others rename the cast of characters: husband and wife become rhinoceros and ox; a carpool driver, the ominous figure Denmother.An elderly female is Old Grandmother, who creates time and granddaughters from oyster stew. The humidity of Deep South summers and steam from Louisiana recipes contribute to a simmering language, out of which people and images emerge and into which they dissolve again.

Denmother went to college in the 60s,

could pin your ears back at a cocktail party.

Her laugh had an edge to it,

and her yard was always cut.She grew twisted herbs in the flower beds,

hid them like weeks among dumpy marigolds.

The wolfsbane killed the pansies

before they bloomed much.She'd look at you real straight and talk

about nuclear power plants or abortion. At home

alone she boiled red potatoes all night

to make the primitive starch that holds up the clouds.

-- "Denmother's Conversation"

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

You Can See It in the Architecture

those masonry double walls and smallish windows, furnace

puffing away, an iron lung just under the carpet floor.

Southern houses are built in fear of heat.

and shawls, and they tend to be young girls dead

of the yellow-fever afterbirth of a baby

that had to be strangled. Built of wood, inside and out,

footed in the flat boggy muck of overflows, raised

above swamp fire, mosquitoes. Roomy closets

stuffed with whatever it is we find to wrap bones in,

a tinderbox, you may have noticed, with bead-board wainscot

or floral wallpapers, and layer on layer of paint and wax.

They say you always become what you most fear.

don’t you know? Old raw cypress smell there,

where the heat collects, builds, heat the downstairs

rooms were designed to hide, to funnel up here,

anymore and the bundles of dry-rot doll clothes.

A dark triangle vault—listen close now, you’ll be glad

you came outside—gluttonous for thermal increase,

till the hot red eye of memory flicks open

underneath its oily gauze bandages

and the whole structure is consumed.

White House in Watercolor

A two-story frame house carves itself

out of a mumble of shadows. Seven windows

sink back, double-sashed, vermilion, sulfur.

In the foreground, filed teeth dazzle

into fence pickets, their bases sheared off

in umbers uneven as wild onion and sourgrass.

the shape, an archangel garment of bleached wool,

nothing to announce. An unpainted oval floats

on the porch wall, a jowled eyeless face.

And the front steps—more unmapped white,

edges erratic with camellia and bay laurel

and notched along one side with telltale right angles

to summon up the dirty boots of uncles.

you could draw once your best friend

taught you the 3-D cube: a box to crawl into

from any side, a box that held nothing.

And it’s not the Three Bears’ tidy house

before the little sneak thief broke and entered,

broke some more and left blond corkscrew hairs

in the nap of the bedspread.

where windows hold back secrets the shade

of fading bruises, and a cotton wad sags

on the screen door against haunts and mosquitoes.

The house where all the accidents happened

that left you the way you are—unable to face

a sheet of bare white paper till it’s brushed over

with color you can’t see through,

painted into uncertain shapes

you only claim to recognize.

Eye Games

to soak through at the first timid request.

I’ll show you. For a moment

your face. Look straight at the charcoal

shadows even now trying to recede.

Take all the time you need. You’ll see

The sables, the carbon blacks open

their hoarse throats, and the real dark

—the dark behind it all—eases in.

a two-dimension film before your eyes.

Rotate your head side to side, nod up/down.

Extrapolate. You’ll find that the plane is small,

that’s no larger than a breakfast room

and you are inside it, sitting in a little highchair

at dead center, maybe a tray in front of you,

All around you, the globe wraps tissue paper scenes,

mainly in pinks and blues, that rumple a bit

along the seams from the clumped paste.

a man’s black shoe here, the skinny hands

of a clock, one sliding behind the other, a daub

of burnt umber on the floor under the bookcase.

cigarette burns, failures in the delicate paper,

and here the humid dark pours through a syrup

of ashes, sticky as oil smoke, bitter with sulfur,

in that chair, the plastic belt cutting across

your soft stomach. You’ve dropped the spoon

and you’ve already learned nobody’s coming

and you’re no longer able to see

the pretty pictures, no longer able

even to believe they are there.

Heat

ran together—our mother’s make-up,

chocolate, the ice blocks in sawdust.

My grandmother knew more

than one way to skin a cat.

She made me a chubby

baby chick out of yellow

modeling clay that lay

down, and in a single

July afternoon,

became an egg.

soft: I know the heat

hiding in the latitudes

waits to reduce us all

like the wax crèche figures

I unwrapped last Advent

season to find the Baby Jesus—

halo and all—melted into a headless

camel of the unlucky Wise Man, himself

dark and shapeless in the manger

with one of Mary’s blue-white arms.

Old Grandmother Magic

I could be a boy

when I kissed my elbow.

in the tropical smell of crushed mimosa,

warm baby’s flesh, contorted myself

all afternoon. The green fruit swayed

my shoulder sockets ached, the sweat

and prickle of failure, an itch

along my neck from the hairy leaves.

I yanked off all the swelling figs

I could reach and watched my little roost

streak slow with gluey milk sap.

my neck is stiffer,

I can’t get my elbow

close to my mouth at all.

or not paying attention,

I’ll notice my son’s elbow, and wonder

how it was he ever did it.

First Grandchild Breaks the Egg with No Shell

I was big sister now, she said; no more crying

for Mama. Too short to use the door latch,

I crawled under a canvas flap. Dark struck me

blind. Hay, yeast, feathers, sweet lime,

where iron teeth snag certain little girls

who stray too far from their mother’s blessing.

From roosts on every side thrummed

a low, lazy sound, almost a growl.

I knew already I’d have to lie: I couldn’t reach

under the three setting hens, humming away

hidden in the dark. I patted empty nests only,

on tiptoe, the way I stretched one-handed

out of sight. My fingers groped into an egg

and felt the yolk. I was poking the head

of a newborn, touching the back of her eyeball.

Egg white and yolk collapsed, ran down

I crossed the daylight to her kitchen,

carried two warm eggs with normal shells.

She heard me out, although I didn’t quite

confess—I blamed it on the egg.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- What the Magnolias Say

- CHOOSING MONOGAMY

- DEPENDABLE HEAT SOURCE

- BABIES’ BONES FROM MAGIC CRYSTALS

- Acknowledgments