![]()

1

THE CHURCH, LANGUAGE, AND POLITICS IN COLONIAL LOUISIANA, 1718–1803

THE FRENCH WAY OF REPRESENTING THE WORLD

While there are many good histories of colonial Louisiana,1 the question of language preferences is rarely raised. The popular assumption is that everyone spoke French except a few Spanish administrators, and that view somewhat approaches the truth. It is also true that this Church was French, again with the exception of some Spanish administrators, and the Crown and Church worked as a team (although as very unequal partners). It is easy to sentimentalize a triumphant scene of a French cavalier landing on the Louisiana shore, proudly planting the French flag, with a robed priest standing close by, eyes heavenward. Unfortunately, historians and church records show that this romantic picture, although flattering to the French colonial self-image, disguises a number of hard realities about trying to establish a colony in the disease-ridden semitropics in the eighteenth century. When we look at language practices in colonial Louisiana, there are also realities that disturb a similarly romanticized image of colonists, laborers, and gentry gathered around a neat colonial church chatting with the priest in Parisian French. Church records show that this image is also a fantasy. For most of the period from the founding of New Orleans in 1718 to Louisiana becoming a state in 1812, both the Church and the French language were in some distress.

Two themes are particularly important in the colonial period concerning the Church as an organization, themes which affected its linguistic behavior subsequently. First, the Catholic Church in Louisiana was always dependent on and subservient to the political and especially financial support of the ruling elite to carry out its mission. The language changes of the nineteenth century were an extension of a hundred and fifty years of prior accommodation in the interest of the survival of its essential mission, the salvation of souls within the body of the Church. The Church’s responses to linguistic, political, and social pressures were always intended to further that mission. But the nineteenth-century Church, freed from its connection to and dependence on any government, pursued that mission in a way that would have shocked the colonial administrators who so openly disdained it.

Second, the Church during the colonial period (and later) considered the native francophone population to be hopelessly poor Catholics as a whole, so that in a sense the exasperated Louisiana French higher clergy were awaiting the arrival of groups who might provide the slothful citizens with a Catholic “Great Awakening.” After the Church found disappointment in immigrant groups such as the Acadians and Haitians, not to mention the Spanish and other European Catholics, the desired group of devout Catholics—the Irish—first put in an appearance in the colonial period in the form of the able Father Thomas Hassett and other Irish priests.

To return to the beginning, however, the French incursion into Louisiana was not exactly a religious crusade but the result of a Nouvelle France colonial adventure authorized by the French Crown, an adventure meant to make money and to thwart the enemies of France who were already operating in North America, notably the British and Spanish. As soon as the French religious wars subsided, the Crown threw itself into colonial expansion to fill its coffers. In the 1690s, colonial outposts were established along the Gulf Coast of the Louisiana Territory, which then spanned from the Gulf of Mexico and the Florida peninsula to the Canadian border. Politically and economically, the venture did not end well for France. In 1763, France was forced to cede Louisiana to Spain. The next half-century was also one of political instability. The Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods ended Spanish rule, but then Napoleon quickly sold the Louisiana Territory to the United States. The decade between the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and its statehood was also turbulent. The Church therefore found itself repeatedly dealing with new, nonfrancophone ruling elites.

Despite such political changes, Louisiana remained markedly French until statehood. Perhaps because of shared Catholicism, the Spanish made only nominal attempts to make Louisiana Hispanic. The successive Spanish administrations were never able to challenge the numerical dominance of French-speaking Louisianans in any case, nor could they convince the founding population that a French identity was less prestigious than a Spanish one.

THE EARLY POLITICAL ADMINISTRATION AND THE CHURCH

Accommodation defined the interactions between church and state from the beginning, with the Catholic Church doing all of the accommodating. This weakness in the Church partly came from a failure of different interest groups within it to put together a united front. The early years of church missions were marked by infighting caused by a lack of formal supervision from distant Quebec and disagreements between Louisiana secular administrators and religious orders.

As was often the pattern, the secular authority had to step in to settle squabbles among colonial religious groups. A ruling from the state secretary for the Navy, dated June 29, 1716, allocated Louisiana colonial posts to the different religious orders that had been battling among one another for dominance.2 But this territory allocation did nothing to encourage French priests to come to Louisiana. Their shortage was a constant lament from the colonial administrators up to the final days of the French regime, and the clergy, in their letters, were often irritable about frontier conditions and homesick. Louisiana’s conciliator Martin Diron d’Artaguiette grumbled about the lack of women in the colonial posts; Governor La Mothe-Cadillac complained about the excessive severity of the missionaries toward the inhabitants; Father Francisco Hidalgo, a Recollet, bemoaned the misery and poverty of the colonial posts; La Mothe-Cadillac and his conciliator, Jean Baptiste Dubois-Ducloc, did not get along and voiced their complaints about one another in many letters.3

NEGOTIATIONS BETWEEN THE CHURCH AND THE CROWN: AN UNEQUAL PARTNERSHIP

The Church in Louisiana was not independent financially. The king’s representative in Nouvelle France was the governor general who supervised, from Quebec, the entire territory divided into three regions: Canada, Acadia, and Louisiana.4 Because of Louisiana’s great distance from Quebec, in December 1712, the Crown created the Conseil Supérieur de la Louisiane (hereafter Superior Council of Louisiana). Its members acted as colonial councillors of the Louisiana posts and later of the city of New Orleans. They fixed prices, acted as a lender, and managed the budget and the land concessions. They also supervised the financial activities of religious congregations. As church historian Charles Nolan noted, “The crown purchased and erected [Louisiana] churches and schools, paid clergy, religious, and sacristan salaries.”5 As in France itself, the state and church powers in Louisiana had traditions, duties, and interests which sometimes intertwined, sometimes not.6 As God’s reflection on earth, the King of France established dioceses, nominated bishops, and authorized missionaries to serve in the colony. At other times, their traditions, duties, and interests opposed one another. Evangelizing the Indians and the slaves was not the duty of the government; trade exploitations did not involve the clergy’s participation although tapping church income did: royal dispatches announcing new church levies were regularly sent to the local clerics.

An excellent example of the interrelationship among the civil administration, the Church, and language can be seen in the effects of the civil law on the culture of people of African descent, mostly slaves, with results quite different from those in other slaveholding areas of North America. The Superior Council of Louisiana created and ruled a complex society that included free, indentured, and slave labor and the relationship of all types of labor. To manage this slaveholding system, Louisiana’s administrators and the Superior Council’s members applied the Customs of Paris or Civil Laws, which set Louisiana apart from the British and anglophone colonies. They also implemented Louis XIV’s “Code Noir,” developed in 1670 to regulate the development of slavery in the French West Indies. The first six articles of the 1724 code concerned the authority of the Catholic Church over the treatment of slaves. The Code Noir mandated that slaves be converted to Catholicism by being instructed and baptized in the Catholic faith, permitted to marry (although they could not do so without the approval of their master, and marriage did not confer to them civil rights), freed from work on Sunday, buried in consecrated ground, and treated humanely. The small religious communities that owned slaves—Jesuits, Capuchins, and Ursulines—were faithful to these rules. But the humane care model displayed by these communities was not emulated by some secular slaveholders, especially those who saw slaves’ transformation into Christian faithful as an impediment to the trading enterprise. Nevertheless, in spite of some planters’ resistance, Christianization via the Code Noir became the most effective method of slave acculturation in Louisiana, as in other French colonial endeavors. Permitting slaves to marry, baptizing slaves and their children, and encouraging other slave owners to respect the rule tied a large number of Africans and their descendants, not only to their owners, but, more importantly, to the French culture, language, and official religion, although in an oblique way.

However closely the Church worked with the Crown, one important fact (noted especially in Charles O’Neill’s Church and State in French Colonial Louisiana) must be kept in mind. From the very start, the Catholic Church was a subordinate element in Louisiana. Local secular authorities viewed the missionaries as frontier diplomats whose role was to facilitate the fur trade and make alliances with the Indian tribes. Restraining “the unruly and licentious habitants and making sober, industrious, and profitable citizens out of them” was also considered the duty of the parish clergy.7 The Church was thus an agent of social control in the service of economic development while having to accept a certain degree of religious inconsistency demanded by the secular authorities. Economic opportunity trumped strict adherence to the rules of the Crown or the Church. According to O’Neill, this opportunistic attitude explains why religious conversion to Catholicism was not enforced in Louisiana. Commercial companies recruited Swiss Reformed soldiers and German Protestant farmers to Louisiana, despite explicit and repeated but unenforced prohibitions from the king. So we see from early on that the Louisiana Catholic Church learned to live side-by-side with those outside the French Catholic culture (a significant departure from the French Crown’s practice) and make the best accommodation it could to retain the financial support needed to maintain the faith. If it took living with German speakers whose grandfathers had savagely oppressed Catholics, so be it.

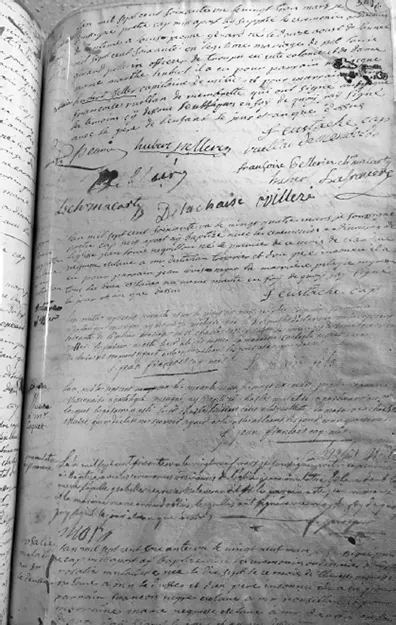

Baptism and marriage register, St. Louis Cathedral, vol. IV, 1759–1763, page 50. (Courtesy of the Office of Archives and Records, Archdiocese of New Orleans.)

THE LOUISIANA POPULATION: A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PORTRAIT

Again, it might be assumed by those unfamiliar with the history of the French language that everybody in Louisiana spoke “French,” meaning what today might be called “school French” or the French as (supposedly) spoken and written in Paris. Thus it might be assumed that all Francophones in Louisiana understood each other perfectly, regardless of their place of origin. Crown officials rarely discussed language issues in their letters, and when they did, they emphasized the importance of native languages. For example, Governor Perier wished that the governor and post commanders would learn how to speak local native languages. Bienville insisted upon the need to learn them in order to improve the colony and to develop bilinguals by sending orphan boys into Indian villages, a practice established in Nouvelle France by Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain.8

In reality, Louisiana colonists were neither culturally nor linguistically homogenous. The first censuses of the founding population between 1705 and 1760 illustrate this diversity, and with regard to the linguistic composition they show two important facts about the social makeup of south Louisiana.9 First, the first African slave population, which was clearly not francophone in origin, came mostly from West African countries such as modern Senegal and Guinea and was brought to Louisiana between 1717 and 1731, at the very beginning of the colony.10 A copy of a census conducted around 1727 by De Chavannes, secretary of the Superior Council of Louisiana, indicates 1,952 inhabitants, 276 indentured servants, 1,540 African slaves, and 229 native Indian slaves. But in New Orleans, the number of African slaves (35%, or 450 out of 1,540) surpassed the white population (31%) and increased further over the next decade.11

As to the white population, the censuses indicate a small population characterized by class and linguistic diversity. Before the founding of New Orleans, only a few hundred settlers, mostly soldiers and slaves, lived on colonial posts. From 1721 to the end of the French colonial period in 1763, fewer than one thousand people from all social ranks came to Louisiana. Among those with financial means, we find planters sponsored by magnate investors in France and in Canada, colonial administrators, clerks, and artisans working for the companies (Crozat’s or Law’s) or for the Crown. Of the great majority below the moneyed classes, soldiers were considered by the planters and administrators to be a low class of inhabitants. Aside from a small group of officers, most were part of a large low-status group of young and illiterate recruits. Besides the planters, administrators, and soldiers, the population had a large contingency of unskilled and skilled indentured settlers. Deportees from France (convicts and indigents) were the dregs of the colony.

These censuses highlight the population’s heterogeneity in origin and language. The majority of Louisiana inhabitants had a mother language other than French. Slaves spoke African languages; settlers from Spain, Italy, and non-French regions that were ultimately annexed by France spoke other languages. But even among the francophone settlers, some spoke mutually unintelligible Gallo-Roman dialects, such as the Franco-Provençal, the Poitevin, the Béarnais, and the Savoyard. Within the French-speaking population, then, many knew nothing of the Ile-de-France dialect (the King’s French).12 One additional fact is relevant: with the exception of the elite, the majority of these Francophones were illiterate, so the relative linguistic unity sometimes imposed on a polyglot population by a common standard written language was absent.13

This standard written language was, however, used by the small group of educated elite in charge of the colony, who wrote and probably spoke the French of the Ile-de-France in order to communicate with the French administration in Paris. Still, even Louisiana administrators spoke a regional dialect as a mother tongue. Quebec French was Governor Bienville’s and Governor Dugué de Boisbriand’s dialect; Governor La Motte-Cadillac spoke Toulousian French, whereas Commissioner De La Chaise’s first language was Auvergnois French. Governor de L’Epinay’s dialect was Breton French but he probably spoke Quebec French as well, having served many years in Canada. Only the small number of French aristocrats was likely to have spoken “pure” French exclusively, but since even in the swamps of Louisiana no respectable aristocrat would ever do office work, colonial endeavors were in the hands of the so-called tiers état, or bourgeoisie, also relatively few. This population never intended to mingle with the settlers, even though their mission was to attract as many as they could. So it appears that the social classes had little social interaction outside of strictly business transactions, and the development of a common dialect was made even more unlikely by this de facto segregation.

Among the Louisiana colonists of modest origins, a large part came from Canada. In fact, letters written by both Louisiana governors and conciliators during the French regime regularly mentioned the presence of French Canadians, who were sought after for many reasons. Unlike immigrants directly from Europe, they had valuable experience with the Indian trade and, consequently, were accepted by many Indian tribes.14 They also knew their way around the vast American interior and, if provided with a wife and a means of subsistence—according to the administrators, anyway—would stay and increase the number of inhabitants. Many did, but the impoverished state of the colony and the unhealthy climate encouraged a high level of outward migration among these resourceful men, who knew where to move when better possibilities appeared.

From this sociolinguistic portrait, several observations can be made. First of all, there was not one original variety of “Louisiana” French during the colonial period. The varieties of spoken French during this era were numerous and were a continuation of those being spoken in France and Nouvelle France. These varieties of French dominated the Louisiana countryside as well a...