![]()

I

THE DAWN OF A NEW ERA

![]()

1

ORIGINS OF FORESTRY IN THE SOUTH

The First Southern Forest. In 1607, when Captain John Smith and his fellow colonists settled on its eastern fringe, the Southern Forest covered 354 million acres. Stretching south and west for more than a thousand miles, the Southern Forest was a majestic array of magnificent, oak, tulip poplar, and cypress; dense, nearly impenetrable swamps; open park-like pine forests; and verdant, cloud-shrouded mountains. To the English colonists, it was a challenging and mysterious wilderness, but to a society of Native Americans, it had been home, garden, and hunting grounds for more than a thousand years.1

Late in pre-Columbian time, an agrarian society, referred to as the Mississippians by anthropologists, lived in organized chiefdoms scattered across the Southern Forest.2 Maize, beans, and squash were the staple crops for this society, although a variety of other species were often produced.3 The Mississippians cleared and cultivated sizable areas. When Hernando de Soto and his army explored parts of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi in 1539, they found “large fields of maize, beans, calabashes, and other vegetable, the fields on both sides of the road extending across the plain out of sight, and it was two leagues [c. 10 km] through them.”4 De Soto and his party were clearly impressed by the bountiful agriculture of the Native Americans. One of De Soto’s men wrote, “So that the abundance and fertility of the province of Apalache may be seen, we say that the whole Spanish army with the Indians whom they carried as servants, numbering in all more than fifteen hundred persons, and more than three hundred horses, in the five months and more that they wintered in this camp maintained themselves on the food that they collected at the beginning, and when they needed it they found it in the small pueblos in the vicinity in such quantities that they never went farther than a league and a half from the principal pueblo to bring it.”5

Estimates of the pre-Columbian population of Native Americans range as high as 100 million,6 a figure which the U.S. Census did not record until 1915! The native population living in the Southern Forest is conservatively estimated to have numbered 1.5 to 2 million, and approximately half of their food supply came from agriculture.7 Thus, the impact of Native American agriculture on the Southern Forest was extensive. And so was the impact of fire. Native Americans made widespread use of fire to reduce the threat to their settlements from wildfire, to aid in land clearing, and to facilitate travel, hunting, and gathering. Anthropogenic burning was especially common in the longleaf–slash pine belt of the Lower Coastal Plain.8 In pre-European longleaf forest, it is estimated that fire consumed, on average, two metric tons of biomass per hectare per year,9 or 20 to 25 percent of above-ground net primary productivity.10

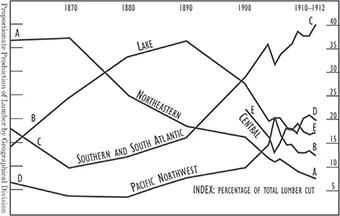

Fig. 1.1. Changes in U.S. lumber production by region between 1860 and 1912: (A) Northeast, (B) Lake States, (C) South, (D) Pacific Northwest, (E) Central States. Redrawn from Compton 1916.

Columbus, de Soto, and those who followed brought with them a plethora of pestilence from the Old World, viruses (smallpox, measles, yellow fever, chickenpox, influenza), bacteria (anthrax, whooping cough, typhus), and parasites (malaria and schistosomes), to which Native Americans had little or no immunity.11 They also introduced an invasive species, razorback hogs, which had a devastating effect on one of the patriarchs of the Southern Forest, longleaf pine.12 Throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, pandemics decimated the Native American population. Mortality has been estimated at 60 to 80 percent.13 Much of the once extensive areas cultivated by Native Americans reverted to forest before the first permanent English colonies were established. But the centuries of human-induced disturbance to the landscape prior to the arrival of John Smith and his fellow colonists did not approach the magnitude and extent of what occurred over the ensuing three hundred years.

Exploitation of the First Forest. By the beginning of the twentieth century, a third of the precolonial Southern Forest had been converted to agriculture, urban, and industrial use. Much of the remainder had been grazed, indiscriminately burned, and exploited for its most valued species. But a broad band of virgin southern pine still spread across the Coastal Plain from the Carolinas to eastern Texas. The lumber industry, having exhausted the best of the forests in New England and the Lake States, began moving south (fig. 1.1). After the Civil War, new railroads connected southern sawmills to the urban and industrial markets of the North. Reopening the ports along the Atlantic and Gulf seaboards provided access to markets in Western Europe and eastern South America. Lumber production in the South rose from 1.5 billion BF* in 1870 to a peak of 21.2 billion BF in 1909. Over the ensuing quarter-century, more than 400 billion BF of lumber were produced from the Southern Forest: 75 percent was southern yellow pine,14 in what has been described as “probably the most rapid and reckless destruction of forest known to history.”15 The Southern Forest was not destroyed in the sense that it was rendered incapable of recovery, but most of it was harvested without any effort to ensure regeneration, and any advanced regeneration that existed was damaged or destroyed by the logging methods used.

Thousands of sawmills ran twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, converting pine, cypress, and hardwood logs to lumber. The largest sawmill in the world was built on Bogue Lusa Creek in southeast Louisiana.16 The mill, log pond, lumber storage yards, dry kilns, and associated buildings occupied over 200 acres. The log pond alone covered 27 acres. In the power house, thirteen boilers fueled with mill waste supplied all the power used by the sawmill, the pulp mill, and the nearby city of Bogalusa. The mill housed four 7-foot head saws and a twin band saw (“Tango”) for smaller logs. One of the head saws was equipped to cut timbers up to 75 feet in length. Running at full capacity, the mill produced a million BF of lumber every 24 hours. Supplying the logs required harvesting 40 to 100 acres of forest a day. Every tree capable of producing a two-by-four board was brought to the mill. Operation began on October 17, 1908, and over the next thirty years the mill produced more than 5 billion BF of southern yellow pine lumber.17

The owner of the mill was the Great Southern Lumber Company. Its harvesting and manufacturing practices were typical of most large sawmills operating in the Southern Forest during the first half of the twentieth century. As the largest consumer of pine logs, it was the largest generator of cutover pine lands. But, unlike many of its contemporaries, Great Southern Lumber Company did not log the last acre of available forest, dismantle the mill, and move on. Long before the log supply became critical, Great Southern launched one of the first, one of the largest, and one of the most successful forest restoration efforts in the Southern Forest.

Conservation and the Birth of Professional Forestry. The first efforts at forest conservation in the United States began shortly after the Revolutionary War, when the ship-building needs of the U.S. Navy prompted Congress to enact forest policies which differed very little from the Royal Navy’s hated Broad Arrow policy of colonial days.18 Most of the white pine needed for ship masts was on state or private forestlands in the Northeast and could not be reserved, but much of the Southern Forest was still in the public domain, so the Navy could and did establish live oak reserves and place restrictions on timbering. Southern frontiersmen paid no more attention to edicts from Washington than they had paid to those from London. Fortunately, the acquisition of Florida and the Louisiana Purchase provided more than enough forest resources to meet the needs of both the U.S. Navy and the local southerners. A broader, more enduring conservation movement began near the end of the nineteenth century, when a sizable number of prominent citizens, politicians, scientists, educators, and journalists came to the realization that the nation’s forest resources were not inexhaustible.19 As a result, several influential nongovernment organizations (NGOs) began to advocate for legislation to curb the indiscriminate exploitation of the nation’s forests.

At its 1873 meeting in Portland, Maine, the American Association for the Advancement of Science appointed a committee of distinguished members to “memorialize Congress and the several State legislatures upon the importance of promoting the cultivation of timber and the preservation of forests.”20 The committee, chaired by Franklin B. Hough, a prominent New York physician and naturalist, drafted a statement of the association’s views and concerns and delivered it to President Ulysses Grant, who forwarded it to Congress in February 1874. In response to the AAAS initiative, Representative William Herndon of Texas introduced a bill providing for the appointment of a commissioner of forestry. However, Congress, preoccupied with other matters, failed to take action on Representative Herndon’s bill. A similar bill was introduced in 1876 by Representative Mark Dunnell of Minnesota. When it too failed to garner sufficient support for passage, Dunnell adopted the expedient of attaching a rider to the 1877 appropriations bill providing

that two thousand dollars . . . shall be expended by the Commissioner of Agriculture as compensation to some man of approved attainments, who is practically well acquainted with methods of statistical inquiry, and who has evinced an intimate acquaintance with questions relating to the national wants in regard to timber to prosecute investigations and inquiries with the view of ascertaining the annual amount of consumption importation and exportation of timber and other forest products, the probable supply for future wants, the means best adapted to their preservation and renewal, the influence of forests upon climate, and the measures that have been successfully applied in foreign countries, or that may be deemed applicable to this country, the preservation and restoration or planting of forest and to report upon the same to the Commissioner of Agriculture, to be transmitted by him in the a special report to Congress.21

The appropriations bill was passed, and the commissioner of agriculture, Frederick Watts, promptly appointed Dr. Hough to undertake the tasks outlined in Representative Dunnell’s rider. This rather trivial earmark in a general appropriations bill initiated one of the most significant developments in the history of natural resource conservation and the practice of forestry in the United States. From this modest beginning arose the USDA–Forest Service.22

In 1875, John A. Warder—a Cincinnati, Ohio, physician, pomologist, and amateur forester—organized a meeting in Chicago of prominent citizens with similar interests and founded the American Forestry Association (since 1992, American Forests).23 In the century and a half since it was formed, this organization has been a prominent and effective advocate for forestry and environmental preservation both nationally and internationally. The association inspired numerous similar state and regional organizations that worked at a local level with regional authorities, state legislatures, and county and municipal officials advocating sustainable forestry and conservation.

In 1889, the American Forestry Association, in a joint effort with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, successfully lobbied President William H. Harrison, Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble, and Congress for the enactment of the Forest Reserve Act of 1891.24 While providing authority for the president to establish forest reserves, the 1891 act made no provision for their use or administration. There followed the Forest Reserve Act of 1897, which became known as “The Organic Administration Act” leading to the establishment of the U.S. National Forest System.25

The American Forestry Association tried to encourage the lumbering industry to practice forestry and take steps to regenerate the virgin forest they were vigorously exploiting. In 1893, the association held a special meeting in Chicago and invited the editors of two leading lumber-industry trade journals to assess the possibility of their industry practicing forestry.26 J. E. Defebaugh, editor of The Timberman, stated flatly that, for the lumbering industry, forestry was financially impractical and could not be widely practiced on private forests lands.

The second speaker, M. L. Saley, editor of the North Western Lumberman, agreed with his colleague that it was not economically feasible for lumbermen to practice forestry at that time....