![]()

1

THE SETTING

Huge swatches of blues and country music do after all come from the

cotton fields in a very real way. Many a seminal song was actually

created there, and even more were spread person to person.

—JOHNNY CASH

The American South is different from the rest of the United States. It always has been, and probably always will be. Though the southern existence is complex, one singular fact has consistently defined the region. That is, there have always been two Souths, one white and one black. The region has always contained two strains of humanity, each with definitive social and cultural components. They represent two populations with distinct and deeply engrained perceptions of one another, and of the world around them. The two Souths are no longer legally segregated, as they were for generations, but they are still separated somewhat by custom and by a mutual wariness and anxiety that never quite goes away even in the modern era. However, despite this constant tension, it is not the separation of the races that makes the South a different place. On the contrary, it is the indisputable reality that the two Souths are actually just one South after all, and that, despite the presence of two races, a common culture exists among the region’s entire population. It is a culture with a long tradition that many times can be heard before it can be visualized, or even recognized, by those immersed in it.

As Darden Asbury Pyron pointed out in his biography of author Margaret Mitchell, “Far into the twentieth century, Southern culture flourished in oral knowledge” and “nurtured word of mouth as a standard means of communication. … Southerners instinctively minded assonance and alliteration; their words formed natural rhythms.” This was certainly the case with southern music, a vibrant form of oral tradition that excited the senses, be it folksongs, hymns, old-time spirituals, juke-joint blues, or country laments sung a capella or accompanied by a guitar, banjo, mandolin, piano, or harmonica. Most southerners preferred singing, playing instruments, and dancing to reading and writing as standard forms of expression. As Edward Ayers wrote in his study of the southern existence, “whether at opera houses or medicine shows, barrelhouses or singing schools, music attracted people of every description.” The region’s music, the blending of black and white words and rhythms, has helped define the South as one world. “It is a southern culture,” James McBride Dabbs once stated, “born of all our people—the immortal spirituals, the blues, the plaintive mountain ballads, the hoedowns—binding us together.” It has always made the South different from a cultural perspective from any other part of the United States. Nowhere else in the country has black and white culture mixed to form such an explosively colorful shade of grey. Country music came out of the South, as did the blues, two powerful forms of musical expression that both have been called quintessentially American. In short, every southerner, regardless of race, can rightly boast that his or her heritage includes a great soundtrack.1

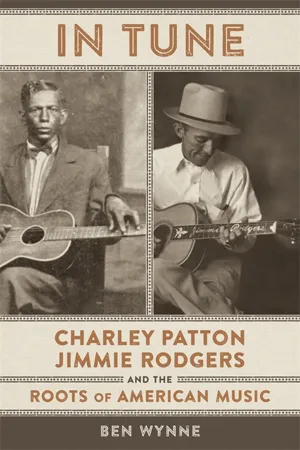

Charley Patton and Jimmie Rodgers were born and raised in the American South, a unique land with a turbulent history that actually began twice. The origins of the South, and indeed of the United States, can be traced back to the year 1607 when a group of 144 men boarded three ships, the Discovery, Godspeed, and Susan Constant, and made the treacherous journey from England to the New World to found the Jamestown colony in Virginia. While this was indeed a landmark event, the history of the South also began twelve years later, in 1619, when a Dutch ship brought in the first “cargo” of Africans to Jamestown. They were around twenty in number and had recently been stolen from a Spanish vessel. The Dutch captain, a man named Jope, exchanged the Africans for food, and then sailed away, leaving them in the colony to serve as laborers. More Africans followed, and within a relatively short time Virginia lawmakers began authoring legislation distinguishing between white and black workers in the colony and providing for more oppressive treatment of African laborers. This was one of the first steps in a process that established chattel slavery in America.2

As the South’s agricultural economy developed, slavery flourished up and down the eastern seaboard. Beginning in the 1620s, Virginians exported tons of tobacco, as did Maryland planters after that colony was founded in 1634. In the 1670s European planters and their slaves relocated from the Caribbean colony of Barbados to South Carolina, creating a rapidly developing plantation economy there grounded in rice and indigo. Georgia’s agricultural economy, also based in rice and indigo, began to expand not long after the British established that colony in 1732.3 Later still, after the American Revolution and the invention of the cotton gin, slavery fueled the South’s cotton economy in new states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, setting the stage for political rancor between the North and the South and eventually civil war. By the time the war began in 1861, slaves represented more than a third of the Confederacy’s total population.

Southern planters of European descent chose to enslave Africans as a people for a number of reasons. Unlike the Native American population, who the Europeans also tried to subordinate, the African population had natural immunities to many of the diseases that the Europeans brought with them to the New World. As a result, they were healthier as a group and therefore more dependable workers. In addition, once they reached America, the Africans were trapped. Unlike the Native Americans on the East Coast, they could not escape into the forests of the American interior and easily blend in with the indigenous population. While these practical considerations were important to the development of slavery in what would become the United States, at the core of the institution was the fact that the Europeans in America were racially biased against Africans, and viewed African culture as inferior. Europeans stereotyped Africans as an uncivilized people with no hope of social redemption. From there it was relatively easy for the ruling classes in places like Virginia, Maryland, and the Carolinas, and later in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, to pass laws subordinating the African population in a manner that they could never subordinate a person of European descent. The importance of racial identity evolved with the institution of slavery, and a rigid social system based on race became the cornerstone of the southern existence. Early on the large planters, and many white southerners in general, created a web of rationalizations dealing with slavery in what became a long, convoluted struggle to justify the institution.4

During the antebellum period no state was more heavily invested in slavery than Mississippi. Congress created the Mississippi Territory in 1798, not long after Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, and from the time Mississippi entered the Union in 1817 cotton and slavery were central components of the state’s economy. At the time of statehood the population stood at 25,000 free whites and 23,000 slaves. Initially, planters along the Mississippi River produced most of the state’s cotton, but as more settlers came the cotton kingdom expanded to other areas. By 1840 Mississippi was the South’s leading cotton producer, and the state’s white population was in the minority. By 1860, the year before the Civil War began, 55 percent of Mississippians were owned by other Mississippians.

The presence of so many slaves in Mississippi created a racially charged atmosphere that radical politicians—those who played on the fears and insecurities of the white population—could easily exploit. In Mississippi, racial awareness was particularly palpable in areas where slaves outnumbered whites in large numbers. For instance, in 1860 cotton-rich Hinds County, which included the state capital at Jackson, had a population of around 9,000 whites and more than 22,000 slaves. These anxieties among the white population eventually gave way to political tensions affecting slaveholding and non-slave-holding whites alike in that they were all intimidated by the sheer number of slaves in their midst coupled with an expanding abolition movement in the North. By the time the Mississippi Secession Convention met in Jackson on the eve of the Civil War, the political leaders in the state were determined to preserve slavery at all costs, even if it meant severing ties with the United States. Poorer, non-slaveholding whites, who represented the majority of the state’s population, were willing to follow this course as well as they had become increasingly fearful of a potentially free black population with whom they would compete for jobs and land. “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery—the greatest material institution in the world,” members of the convention stated emphatically as they voted to leave the Union, “There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles have been subverted to work out our ruin.” During the war’s first year, white Mississippians were not shy in signing up to fight, and over time more than 60,000 white Mississippians took part in the conflict, a third of whom perished. Conversely, around 17,000 former slaves from Mississippi ended up fighting for the Union before the war’s end. From the time that federal armies first began moving through the state, slaves flocked to the lines seeking freedom, and many male slaves chose to support the war by signing up for military service. They saw their efforts as a chance to help create a new “southern way of life” in which their people and culture could fully thrive.5

Mississippi Population Statistics, 1820–1860 (% total)

| YEAR | FREE | SLAVE | TOTAL |

| 1820 | 42,175 (56%) | 32,272 (44%) | 75,447 |

| 1830 | 70,433 (52%) | 65,659 (48%) | 136,092 |

| 1840 | 179,074 (48%) | 195,211 (52%) | 374,285 |

| 1850 | 295,718 (49%) | 309,874 (51%) | 605,592 |

| 1860 | 353,899 (45%) | 436,631 (55%) | 790,530 |

Source: U.S. Census data.

While the South changed in some ways after the Civil War, in other ways the region remained the same. Before the Civil War, masters controlled every aspect of their slaves’ lives. Even if they could not break their slaves’ spirit, they exercised complete control of their physical being. The master literally owned and controlled the bodies that were in the field picking cotton in the same way that he owned and controlled the body of a mule that he used to pull a wagon. The slave owner’s place in this one-sided relationship could sometimes be intoxicating. As noted psychologist John Dollard once wrote, “Actually to own the body of another person and to control it completely is probably the most exalting possibility from the standpoint of the owner’s self-esteem.” In the South the master was not merely a master, he was not just a boss or an owner, and he was much more than just a patriarch in the ruling classes. In the small universe of the plantation he was a god, a man who could alter other men’s futures on a whim. He could break up families with the stroke of a pen and routinely issued orders that he expected others to follow immediately and without demur. Southern slave owners, particularly those in the white ruling class, suddenly and dramatically lost this wellspring of self-esteem and sense of power as a result of the Civil War, and after Reconstruction they and their heirs wanted it back. Seeing it as a threat to their own status, the poorer classes of whites were also uncomfortable with any new system that empowered the former slaves. Ultimately this all led to the systematic stripping of civil and political rights from former slaves in an effort to subjugate them and establish their race as inferior in much the same manner that slavery had.6

While slavery was eliminated by the war’s outcome, the social problems related to the institution did not go away. In fact, they were magnified. During the Reconstruction period the federal government under the control of the Republican Party supported the creation of state governments in the South that offered African Americans the opportunity to participate in the political process. While these governments functioned for a time, they eventually fell prey to northern apathy and massive resistance from a major segment of the South’s white population. As the Reconstruction period wore on, many whites in the North lost interest in the process while the white power structure in the South fought to regain control of the southern state governments by any means possible. Through voter fraud and violence promoted by political leaders as well as by the Ku Klux Klan and other domestic terrorist organizations, the conservative Democratic Party emerged during the 1870s as the party of white supremacy in the South. Democratic leaders used racial politics and Confederate imagery to consolidate their power by appealing to white voters on an emotional level. The Democratic Party organization became dominant in what became a one-party political system in the states of the former Confederacy. Once in control, the Democrats took further steps to turn back the clock and recreate the old social system that had existed before the war.7

With slavery abolished, citizenship defined, and voting rights protected by the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments to the U.S. Constitution, the Democratic power structure in the southern states struggled to create oppressive, race-based legislation to lay the foundation for a new system that was meant to replicate the old as closely as possible. In the Old South, master and slave could not occupy the same legal status; hence, the same needed to be the case in the new environment. Just as the old slave system had rested on the premise of African American subordination, the new system of segregation began with clearly defined notions of racial inferiority and superiority. The old system had been based on control—the control of masters over their slaves— so the new system must also rest on the control of one group over another. With slavery outlawed, legal chicanery, usually in the form of laws established and enforced with a wink and nod, became the weapon of choice in the states of the former Confederacy in their fight to reestablish something close to the old order. Prime examples were the so-called “vagrancy” laws that southern legislatures established after the Civil War. Technically, attorneys and legislators wrote the laws in racially neutral terms, but in practical application they were meant to subordinate one race over the other. Many of the laws revolved around labor and labor contracts in the new world that emancipation had created. Any African American who refused to sign a work contract that a white landowner might offer could be jailed as a vagrant, which was defined in Mississippi as a person who was not holding a job at the specific instant that white authorities chose to arrest him. After being charged as a vagrant, the man would then have to remain in jail until he paid a fine, even though he had no job or income. The final part of the equation involved someone else paying the vagrant’s fine for him, after which the vagrant was required to work off the debt without wages. The former master was usually given preference in paying the fine of one of his former slaves, thereby completing a cycle that effectively made the former bondsman a slave again. “Vagrancy and enticement laws soon characterized the whole of the former Confederacy,” Houston A. Baker Jr. wrote, “Convicted blacks were seldom (if ever) equipped to pay exorbitant fines levied against them. Hence, they were released into the custody of the white person who covered their court cost and fines. Then the true incarceration began.” More oppressive legislative followed, such as laws requiring “agricultural laborers” to work from dawn until dusk every day except Sunday, and statutes requiring that workers should remain on the plantation even when they were not working. In some places workers were not allowed visitors unless they received permission from their employer. The end result was a skewed legal system for “white criminalization of black bodies in order to supply labor demands.”8

Segregation laws, collectively called “Jim Crow” laws, served as the foundation for subordinating the African American population in the South following the Civil War and Reconstruction, and they were well entrenched in the southern states by the turn of the twentieth century. These laws forbade blacks to enter any public accommodation frequented by whites, meaning that the races could not mingle in public parks, could not stay in the same hotels, eat together in the same restaurants, or ride in the same railroad cars. They had to drink from separate water fountains and use separate public restrooms; later laws would be passed that even segregated “black” and “white” vending machines. The states of the old Confederacy also established separate school systems for black and white children, the mere presence of which foreshadowed the segregated world that black and white youngsters would enter as adults. As southern solons established the Jim Crow system of segregation, they were also busy neutralizing the black vote using vehicles such as poll taxes, literacy requirements for voter registration, and grandfather clauses that allowed the descendants of antebellum whites to vote but not the descendants of antebellum slaves. As Jennifer Lynn Ritterhouse stated in her study of the Jim Crow South, the white governing class attempted in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to undo what the war and Reconstruction had wrought through “not only the subjugation of free black labor and the expulsion of blacks from electoral politics, but also the reassertion of a code of domination rooted in slavery—in short, racial etiquette.” The result was a social and political system that mirrored the antebellum environment, at least to the extent that disenfranchisement and segregation denied certain rights to large segments of the southern population based on their race. It subordinated the African American population economically and in the field of politics, giving them very little control over their condition. It was, as Neil McMillen stated, “a system of racial segregation, degradation, and repression designed to stifle their initiative, insure their poverty and illiteracy, and isolate them from American democratic values, and render them politically powerless.”9

Of course the new system, like the old, generated constant social friction. Just as they had been wary of outside influences during slavery, white southerners became acutely aware of anything different that appeared in their community once segregation was in place. They were suspicious of outsiders who might come in with new ideas that might somehow upset a southern “way of life” that was both new and old at the same time. As the rest of the country matured during the early twentieth century, the South continued to lag behind in quasi-isolation. Southern African Americans knew where they could and could not go, as did southern whites, and everyone knew that there were strict limits to every type of interaction that took place between the races. As author Gayle Graham Yates, a white Mississippian who grew up in the Jim Crow South, later reflected, “When we were children, ironclad ancestry was racial and racial identity definitive. People were either black or white. Even if some tanned white people might be darker than some blacks and if some blacks were whiter than whites, we all knew instantly who was which.” In this environment, new ideas that came from other places tended to be viewed with suspicion that sometimes gave way to paranoia. People from other regions, some southerners claimed, did not understand the “special problems” caused by the presence of two races living in such close proximity to one another. “As culture, southern segregation made a new collective white identity,” Grace Elizabeth Hale observed. “Reconstruction dissolved into a formless recapitulation of the war [where] former Confederates fought the freedpeople’s voting, office-holding and land ownership.”10 Meanwhile, most northerners grew tired of the controversy that civil rights issues generated, and for decades the federal government did little to combat the abuses against African Americans in the South.

Just as Mississippi was immersed in the antebellum cotton culture, the home state of Charley Patton and Jimmie Rodgers was at the forefront of implementing and enforcing segregation laws. In 1890 the Mississippi legislature called a convention to create a new state constitution that included Jim Crow statutes and reinforced white political domination by disenfranchising most of the state’s black population. “Our chief duty when we meet in convention,” Mississippi’s U.S. Senator James Z. George declared shortly before the meeting, “is to devise such measures … as will enable us to maintain home government, under the co...