![]()

1

Defining Interwar Naturism in Theory and Practice

The Drs. Durville

Two brothers and doctors, Gaston and André Durville, justified their approach to naturism and nudism in 1929: “Isn’t it preferable to recruit five hundred thousand moderate naturists in France who really practice, and who… will progressively get a taste for sport in the open air, than to attract five or six hundred nudist naturists [naturistes nudistes] who are already convinced practitioners? We want, before all else, that healthful naturist ideas spread to the mass of French people [emphasis in the original].”1 In the interwar years, having already developed ideas about proper diets and the practice of medicine without drugs, the Durville brothers focused on the importance of physical activity in the open air as both a preventive measure and as a cure for virtually any malady that might befall a human being. In the process, by improving individual bodies, they could “regenerate” France. Like so many others, they spoke to French cultural anxieties about presumed depopulation, the perils of disease (especially tuberculosis and syphilis), and the supposed weakness of the French social body in the wake of World War I. Yet the Durvilles had a very different prescription from the pronatalists, interwar critics of modernity, modernization, or “Americanization,” and French officials who blamed luxury, couples’ and especially women’s selfishness, and workers’ disease-ridden slums for France’s perceived troubles.2 For the Durvilles, a comprehensive approach to naturism alone could solve France’s apparent problems.

The Durvilles played a key role in advocating naturism in France to “save” the French nation through nearly nude, mixed-sex exercise and leisure in the fresh air, under the sun, in the water, and, for the hardy, even in the snow. And they almost included complete, mixed-sex nudism as part of their program. Yet, when forced to choose publicly, they claimed that amateur sports in the open air for the barely clad multitudes were preferable to the risks entailed by championing nudism. It would prove a wise choice in interwar France. It allowed the Durvilles to become successful champions of naturism, welcoming up to two thousand practitioners on a nice day at their first installation near Paris, while many thousands more read their various publications. Although they clearly toyed with publicly advocating nudism, even sounding out their followers and the police, in the late 1920s such a move would have jeopardized their profitable medical business and their credibility among the “mass of French people,” as they put it. Instead the Durvilles and many of their followers practiced nudism at home and clandestinely out-of-doors while outwardly condemning mixed-sex nudity at their centers. Although this approach would earn the Durvilles the derisive label of “hypocrite” from their primary rival, Marcel Kienné de Mongeot, they profited handsomely from it.

The experience of the Drs. Durville in the interwar years reveals a critical transition of naturism from medical theory to leisure-time practice. On the one hand, the Durvilles clearly reinforced continuities of naturism from before World War I. They focused heavily on the importance of diet; in that, their medical advice differed little from earlier and contemporary naturist doctors, most notably Paul Carton. They stressed physical activity, particularly out of doors, following in the footsteps of Georges Hébert, and this emphasis also differed little from that of other naturists. Their naturism rested heavily on aesthetics; naturist bodies needed to be beautiful, and the effort to make bodies beautiful would, according to the Durvilles, be good for individual health and for France. On the other hand, the Durvilles established naturist centers for sport and leisure, both in greater Paris and on the Mediterranean, laying the groundwork for the rapid expansion of nude tourism after the Second World War.

While naturism had clearly meant an appropriate diet, exercise, and fresh air at the end of World War I, by 1939 it meant spending time outdoors sunbathing and swimming in little or no clothes. The actions of the Durville brothers thus reflect the slow evolution of French norms governing exposed bodies in the interwar years. The Durvilles’ decisions reveal that, while small nudist groups were clearly forming in interwar France, there was still somewhat limited demand among the French for mixed-sex public nudism. Broader public acceptance was out of the question. Traditional assumptions about the implicitly sexual nature of complete nudity prevailed. Responding to that fact, the Drs. Durvilles opted instead for very limited sportswear publicly and nudism on the sly. Moreover, when examined in detail, despite the Durvilles’ flirtation with mixed-sex collective nudism, their notion of naturism was clearly not so much “liberation” of the body, so much as a new program of controlled improvement of the body, and France generally. In the end, the Durvilles’ careful prescriptions of diet, of exercise, of precisely what one needed to wear at their centers, and of aesthetics, amounted to a new regulation of the body, but a regulation nonetheless.

NATURISME CHEZ LES DURVILLES

For Gaston and André Durville, alternative medicine was a family business. Their father, Hector Durville (1849–1923), was a financially successful practitioner and theorist of “magnetism” and hypnosis in the tradition of “mesmerism” that had been so important in the eighteenth century. As a medical theory, “magnetism” held that there were “natural forces, for the most part not exploited, that existed in human beings and in nature.”3 The objective was to “free,” physiologically and psychologically, those forces to promote good health. The theoretical proximity to naturism, as it had been defined in Germany, Britain, and France in the course of the nineteenth century was obvious, particularly as compared to the ultimately dominant model of allopathic medicine.4 Germ theory was not quickly accepted as medical doctrine in France,5 and Durville offered an appealing alternative. He founded the Journal du magnétisme, du massage et de la psychologie and established a Clinique du Magnétisme in Paris, which offered care as well as theoretical and practical courses in his approach. He founded the Société Magnétique de France and published a host of books as part of his own Librairie du Magnétisme. His sons initially followed in their father’s footsteps. The middle child, Henri (b. 1891), continued his father’s work and published a host of works on alternative medical practices. Gaston (b. 1887) and André Durville (b. 1896) earned medical degrees and would lead efforts to promote naturism in France. The eldest brother, Gaston Durville, was the first to get his medical degree in 1911, though the unconventional nature of his thesis, on hypnosis as medical treatment, earned it the mention “médiocre” from the famed Faculté de Médicine de Montpellier.6

As part of his training, Gaston Durville undertook an internship at the sanitarium at Brévannes, where Dr. Paul Carton practiced. While Carton would later stridently condemn the Durvilles and all other interwar naturists perceived as rivals, Carton’s influence on them, and Gaston Durville in particular, was pronounced. Although Carton’s ideas evolved considerably during and after the First World War, his immediate prewar emphasis on nutrition had a lasting impact on the young Gaston Durville and eventually on his younger brother André.

Born in 1875, Carton had been diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1901. A medical student at the time, he followed the prescribed course of care. Following standard treatments of the day, Carton underwent numerous surgeries and other treatments. Most notably, he was supposed to gain strength with a rich diet (suralimentation), which included up to 150 grams (5.3 ounces) of raw meat and twelve eggs daily. His condition worsened, to the point that he became convinced that his body was being poisoned by too much, and the wrong kinds of, food (intoxication alimentaire). At Brévannes, aside from the fresh air, he found not only that fewer calories improved his health but that the source of those calories was critical. He found in the vegetarianism of the naturist movement a solution; henceforth he eschewed meat, and championed the healthfulness of vegetables, fruits, and whole-grain bread. He joined the Société Végétarienne de France, did numerous lectures on behalf of the organization, wrote articles for the periodical La réforme alimentaire,7 and published works on the centrality of the diet for good health.8 He ultimately published some thirty-two books on various aspects of naturism.

Gaston Durville not only largely accepted Carton’s ideas about diet but also began immediately to popularize them. Already before the First World War, Durville himself gave lectures on how the proper diet could help human beings live longer. Elaborated in a cheaply produced paperback, L’Art de vivre longtemps: Comment prolonger la vie par l’alimentation saine, Durville’s advice found a receptive audience, one that grew after the war.9 It is now both a cliché and an understatement to note that World War I exacerbated European concerns about the perceived decline of Europe, of their own nations, of national birthrates, of health and hygiene, and of the national and white races. And while Durville said remarkably little about the disabled bodies omnipresent in Europe after the First World War, that was precisely the context in which Durville’s (and other naturists’) ideas about perfecting bodies through nutrition and exercise appeared, and it explains at least part of the appeal as those ideas steadily gained traction in the interwar years.

According to Gaston Durville, human beings, properly cared for, could live to age 150. The problem, he maintained, was that people poison themselves. Only thoroughgoing reform of the diet could head off disaster. Using the language of race rather vaguely, potentially meaning one’s family line, the “French race,” “the European (white) race,” or the “human race” in a way not at all infrequent before the Third Reich and the Second World War,10 Durville claimed that “every man concerned about his own health and who considers the future of the race must follow a [naturist] diet.”11 Thus, instead of focusing on microbes, as Louis Pasteur had, Durville’s contemporaries needed to eliminate the “degeneration” due to the “luxury” (luxe) of the modern diet, and he was particularly critical of the richness of traditional French cuisine; nineteenth-century gourmet Jean-Anthelme Brillat-Savarin was a particular object of scorn. Instead, simplicity should be the rule. The three biggest dangers, according to Durville, were processed sugar, alcohol, and red meat, which he equated by covering all three in the same chapter. Praising the American temperance movement as a model, Durville argued that sugar and meat were no better. Like alcohol, they led to arthritis, tuberculosis, and cancer. Meat came under special scrutiny for raising cholesterol levels and increasing incidence of arteriosclerosis. Instead, people needed to eat wholegrain bread (“the whiter the bread, the less nutritious”),12 green vegetables, and fully ripe fruit. Food needed to be fresh, not canned. A diet rich in whole grains, fruits, and vegetables would stave off constipation, “the great illness of this century.”13 And that food needed to be chewed slowly and thoroughly. Above all, overeating, which he considered endemic to his society, needed to be avoided at all cost.

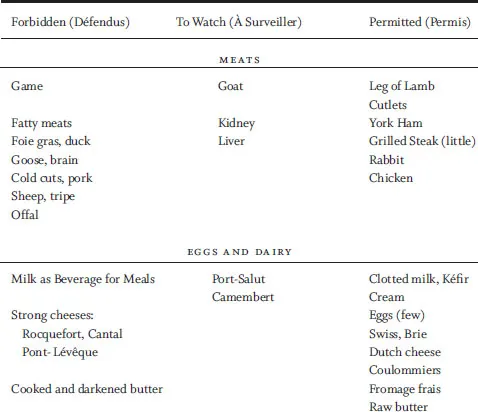

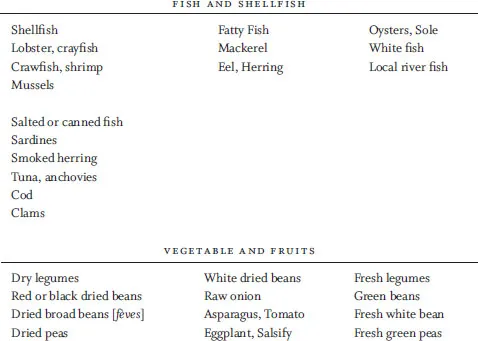

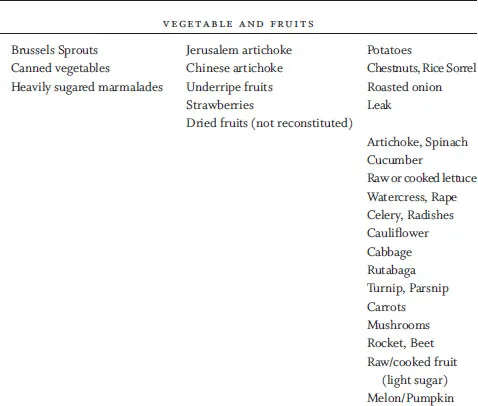

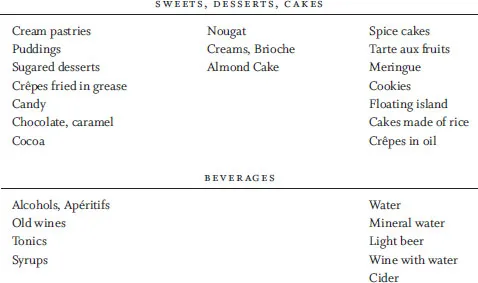

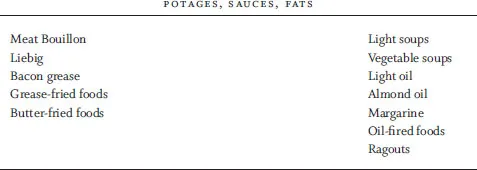

Yet, as for Carton, it was not just an issue of how much should be eaten or avoiding a few foods. For Durville, various foods were bad, not to be eaten; or permitted, so long as one did not overeat. Durville’s quite detailed list reveals how carefully one should eat in order to avoid “alimentary intoxication,” illness, and a shortened life span. By laying out foods under categories, Durville in essence set up a sort of “eat this, not that,” which foreshadowed later twentieth-century notions of maintaining health by eating certain foods and avoiding others.14

From a twenty-first-century nutritional perspective, Durville’s list is riddled with contradictions (for example, tuna and shellfish are bad, but ham and leg of lamb are good; milk with a meal is bad, but cream and Brie are good). Durville had complicated ideas about the density of foods and their chemical compositions that have not withstood the scrutiny of nutritional research. Yet in many ways Durville seems prescient in prescribing a reasonably healthy diet for largely sedentary individuals; this is certainly a far cry from earlier notions that plenty of meat and wine would make one strong and healthy.

Gaston Durville’s Approved Foods

Source: Gaston Durville, L’Art de vivre longtemps: Comment prolonger la vie par l’alimentation saine (1912; Paris: Institut de Médicine Naturelle, n.d. [sometime after 1924]), 92–94.

While not insisting on full-fledged vegetarianism for all, Durville did suggest moderate, limited consumption of meat and fish, which he advised to be eaten no more than two to three times per week for those who were healthy. For those already “intoxicated” by overeating, a strictly vegetarian diet was ideal. He also specified when various food groups should be eaten; quoting early naturist Dr. Albert Monteuuis, Durville noted that ideally “‘A meal should be fruit in the morning, limited meat at midday [when the French traditionally ate their largest meal], and vegetables in the evening [when the French traditionally ate light and rather late, not long before bedtime].’”15

Gaston Durville’s medical advice was in no way limited to food. By the end of the war, he had published the first edition of La Cure naturiste, in which the Durvilles’ medical treatments were laid out in some detail. This book reappeared in several editions, and its ideas also appeared, in very accessible short articles, in their periodical La Vie sage from 1923 to 1930 as well as in its successor, Naturisme, beginning in 1930.16 In 1924, André Durville received his own medical degree; henceforth Gaston and André Durville, with some assistance from Henri, worked as a veritable naturist medical team. The Durvilles practiced hypnosis, psychotherapy, and various other psychological treatments as well as physical massage in order to “return” patients to an original, presumably healthy, state. For massages, they made frequent use of x-rays—they saw themselves very much as “modern” doctors—in order to determine where body parts were, as compared to where they should be, thus confirming the importance of eating properly to keep the stomach and intestines properly sized and physical manipulation through massage to keep organs in their ideal positions. Obviously, the Durvilles’ notion of naturism was not some laissez-faire approach of, as Gaston Durville put it, having “man walk around naked, eating roots” or whatever he pleased, but a highly controlled, medically supervised “return to nature.”17 Close to hom...