![]()

1

PEKING

COVERING THE CIVIL WAR

The Chinese Communist official in the black tunic scrutinized me skeptically as I stood before his desk in the uniform of a recently promoted U.S. Army captain. I had just identified myself as a correspondent for the International News Service. An amused expression replaced the frown as I explained that I was newly arrived in Peking from Manila, still on terminal military leave, and I had not yet found time to buy civilian clothes. The Communist official was Huang Hua, and this meeting in September 1946 was the first of many encounters with him, some at historical junctures when he was a key figure in shaping relations between the United States and China.

I had stopped at Huang Hua’s desk while making the rounds of Executive Headquarters, the truce organization established by President Truman’s envoy, General George C. Marshall, who arrived in China on December 20, 1945, with the mission of bringing about an end to the Civil War between the forces of Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong. Before approaching Huang Hua, who was the spokesman for the Communist branch of Executive Headquarters, I had introduced myself to the American commissioner, Walter Robertson, and to the American military officers, who were so numerous that Peking residents jokingly spoke of the headquarters, which was housed in the former Peking Union Medical College, as the “Temple of One Thousand Sleeping Colonels.” Marshall at this moment was in Chungking attempting to bring the two warring factions into a coalition government. From Executive Headquarters, American, Nationalist, and Communist commissioners were sending out joint truce teams to battlefields to resolve violations of the cease-fire agreement negotiated by Marshall on January 13, 1945. Huang Hua was the personal aide to as well as spokesman for the Communist commissioner, General Ye Jianying, chief of the general staff of the People’s Liberation Army.

I hastened from my meeting with Huang Hua to Morrison Street, a thoroughfare lined with shops hawking everything from forbidden opium to precious antiques. There I found a Chinese tailor who promised to outfit me overnight in civilian garb. While being measured, peering through the tailor shop window, I watched the traffic on Morrison Street, which ran north–south linking the massive ancient gates of the walled city. Rickshaws and bicycles went by in large number, along with vintage foreign-made cars, and an occasional dust-laden camel or donkey caravan trekking in from the edges of the Gobi Desert. It was impossible to foretell that in August 2008 this same thoroughfare, renamed Wangfujing, would be lined with glistening office skyscrapers, high-rise apartment houses, and fashionable department stores and thronged with thousands of tourists attending the Olympic Games.

Within days of my arrival, decked out in the ill-fitting pinstriped suit with massive shoulder pads made by the Chinese tailor, I was swapping gossip with other correspondents at the bar of the elegant Peking Club and lunching there with sources in the diplomatic community. I chatted with Andrei M. Ledovsky, the Russian consul general, who would later rank as the leading Soviet specialist and historian on East Asian affairs. I lived at first in the dormitory of the College of Chinese Studies, a Christian missionary-supported institution. When not out reporting, I took language lessons there from a bespectacled Mandarin-like professor who insisted that I apply myself rigorously and had me practicing Chinese tones endlessly. For generations the college had provided language training to foreign missionaries, military men, and businessmen. Among the people I met at the school was a former Louisiana schoolteacher who was simply boarding there. She was one of a number of unattached foreign women sashaying those days about China, slipping from one job to another, some becoming consorts of wealthy Chinese. She told me tales of her affair with a Chinese general. She would become Joan Taylor, a character in my first novel, The Peking Letter, published in 1999. In the warlord days of 1922, Chester Ronning, my future father-in-law, and his wife, Inga, then Lutheran missionaries, were students at the school in the company of General Joseph W. Stillwell and his wife, Win. Stillwell made extensive use of his Chinese during the war against Japan. Chinese divisions were deployed under his command in the operations against the Japanese which opened the vital Burma Road, the main overland route for delivery of supplies to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s forces. Quarrels with Chiang, stemming from what Stillwell considered the Generalissimo’s inept leadership in the war against Japan, led to the general’s recall by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

After several months, I left the school dormitory to share a house with Captain David Galula, a brilliant young French assistant military attaché, who confided in me details of the briefings he was getting from his excellent Chinese and diplomatic sources. Galula went from Peking in the next years to observing insurgencies in Greece and Southeast Asia. In 1963 at Harvard University he wrote the book Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, which was still being quoted in 2005 by Americans searching for stratagems to cope with the insurgency in Iraq. The College of Chinese Studies was located in Peking’s Inner City, known as the old Manchu or Tartar city, which embraced the Forbidden City and the Legation Quarter. When Chiang Kai-shek moved the capital south to Nanking (later rendered in Pinyin as Nanjing), the foreign embassies followed; only their consulates remained open in the Legation Quarter. On some evenings Galula and I would go by rickshaw down the narrow, cobbled toutiao hutung (alleyways) along Hatamen Street, past the crimson walls of the Forbidden City, pausing at times to gaze at the purple and golden tile roofs of its palaces and temples before being wheeled through the Front Gate of the Outer City into the old Chinese quarter. There we would loll in the boisterous wine shops exchanging gossip and quips with Chinese acquaintances, at times visiting the company houses where slim joy girls with tinkling voices in silken cheongsams slit to the thigh offered jasmine tea and other delights.

Persuaded that I was a correspondent and not some kind of a spy, Huang Hua dined with me in the fabulous duck and Mongolian restaurants where conversation was enhanced with cups of hsiao hsin, the hot yellow wine. A trim man of thirty-eight, with a quick smile, he spoke good English and enjoyed chatting and tilting ideologically with American correspondents. One of his closest friends was the American journalist Edgar Snow. In 1936, when Huang Hua was a militant leader of the underground student movement at Yenching University (later Peking University) and being hunted by the Nationalist secret police, Snow provided him with refuge in his Peking apartment. Later that year, Huang Hua joined the Communist Party and slipped out of Peking to meet Snow in the cave city of Yenan. Two years earlier, facing annihilation by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces in the Civil War, the Red Army had made the 8,000-mile Long March to the Yen River valley. In Yenan, Huang Hua served as translator and recorder for the American journalist when he interviewed Mao and other Communist leaders for his book.

Huang Hua was intensely curious about the United States. He would bring books about America to my room in the college’s monastic stone dormitory, and we would spend many hours discussing their contents. It was a harbinger of his future extensive involvements with the United States. In 1949, after the Communist occupation of Nanking, he became Premier Zhou Enlai’s envoy in negotiations with J. Leighton Stuart, the American ambassador in Nanking, when Mao was seeking Washington’s recognition. He was the chief delegate confronting the Americans at the Panmunjom peace negotiations during the Korean War. Later, he would become the first ambassador of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations and then foreign minister. He would be at the airfield in July 1971 to welcome Henry Kissinger when the national security adviser arrived secretly to prepare for President Nixon’s historic visit to China.

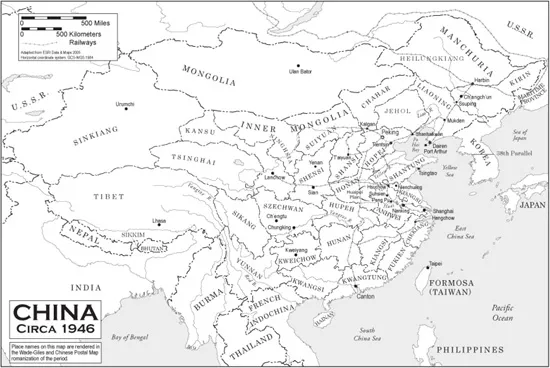

When the Civil War reignited in 1946 in full fury, I seized every opportunity to fly to the remote battlefields of North China and Manchuria to report on the collision of hundreds of thousands of troops in some of the largest battles in history. Little or no news was reaching the outside world about these battles during which many tens of thousands of combatants and civilians were killed. My first trip in September was to Communist-besieged Tat’ung, a coal-mining and industrial city which lay in a basin surrounded by mountains in northern Shansi Province, between the Inner and Outer Great Wall. I traveled aboard an Executive Headquarters plane with a truce team made up of American, Nationalist, and Communist delegates. We landed on a rough airstrip outside the city encased by massive walls. Passing through the Communist lines under a flag of truce, we crossed a wide moat, went through a strangely incongruous electrified barbed-wire fence, and entered Tat’ung through its towering ancient gate. Inside the isolated city, garrisoned by 10,000 Nationalist troops, more than 100,000 inhabitants were carrying on their daily lives stoically awaiting the impending Communist assault. The truce team made no progress in its talks with either the garrison commander or his Communist besiegers, commanded by General He Long. The January 13 cease-fire which General Marshall had arranged in Chungking with Chiang Kai-shek and Zhou Enlai, the Communist negotiator, was no longer being complied with by either side. Several days after our departure, General He Long’s Communist forces stormed Tat’ung and seized the Northern Gate. But he was compelled to break off the attack, having suffered some 10,000 casualties, as a Nationalist column, including mounted cavalry, commanded by General Fu Tso-yi, approached the city. Exploiting the Communist retreat, Fu continued his advance and on October 10 took Kalgan, the capital of Chahar Province (named after a Mongolian clan and in 1952 incorporated into Inner Mongolia), which was the principal Communist stronghold in North China.

Shortly after his victory, I flew to Kalgan to interview Fu Tso-yi, one of the most remarkable of the Nationalist generals. A stout, good-humored man, the general had held sway for years as a warlord in Suiyuan Province (now part of Inner Mongolia), with a regional army of nearly a half million men loyal solely to him. Through efficient and relatively enlightened rule he had earned the devotion of the peasantry and was widely respected as a just ruler by the Communists as well as the Nationalists. His seizure of Kalgan, a city of some 200,000 near the Great Wall, was a severe blow to the Communists. After accepting the surrender of the city by Japanese occupiers in 1945, the Communists had transformed Kalgan into a major communications center, where it also established the North China Associated University. In taking the city, Fu partially blocked the Communists’ vital corridor extending from Central and North China to Communist-held areas in northern Manchuria. General Nie Rongzhen, the Communist regional commander, withstood three days of bombing by Nationalist planes as Fu Tso-yi’s cavalry approached, before abandoning the city. Foreseeing accurately a time when he would recapture the city, Nie did not destroy the railroad yards, the six key river bridges, or the large tobacco factory before he retreated.

In Kalgan I stayed at a hostelry that no longer bore the Communist-given name of “Liberation Hotel.” Fu welcomed me warmly, briefed me on his Tat’ung and Kalgan campaigns, and then put on a show with a ride past one of his famed cavalry units mounted on the small rugged Mongolian ponies which the Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan rode in their conquests of Asia and eastern Europe. The use of these horsemen in the drive on Kalgan may have been the last time in history that mounted cavalry was employed in a major military operation. The general also provided me with an escort for a visit to the Belgian Catholic mission at the Inner Mongolian village of Siwantse, thirty miles north of Kalgan. I toured the mission’s twin-towered cathedral, erected in the eighteenth century, which loomed over an adjacent seminary and convent. I stayed that night in one of the outlying parish compounds whose priest had the job of sending supplies farther into the interior to other clergy in isolated areas who worked as farmers and teachers while propagating their faith. Awake near midnight, I saw a lantern shining in the courtyard and going there found the priest in the freezing weather hauling water from the well. I offered to help and then asked how he endured his arduous daily labor. “Oh, I have good news,” he said. “The Vatican is sending another priest to help me.” “Good,” I said. “When do you expect him?” “He will come, perhaps in two years,” the priest replied. He was typical of other Catholic missionaries I met in remote areas living in the most spartan conditions.

Several weeks after my visit to Siwantse, I learned from the Nationalist-censored press that there had been a guerrilla raid on the mountain village. The defending local militia had been massacred, and before going off on the following day the guerrillas had burned the church and other buildings of the mission, including the library with its priceless collection of ancient Tibetan and Mongolian manuscripts. Several of the Belgian priests were said to have been kidnapped. While Nationalist officials described the raiding guerrillas as Communists, the manner in which Siwantse had been savaged and then abandoned, as I noted in my dispatch, suggested that they might not have been Communists but bandits, many of whom operated in the noman’s-land between the contending armies.

Traveling with the truce teams to battlegrounds throughout North China and Manchuria, I found the members courageous and willing but ineffective. General Alvin Gillem, the senior American officer, complained that neither of the two Chinese sides fulfilled commitments they made to disengage the combatants. They signed agreements which they knew they were not going to keep, he said. So the American side could do nothing but get signatures, knowing that those agreements and the accompanying documents had no practical value. In January 1947, when the Marshall mediating mission finally collapsed, Executive Headquarters was closed down.

In early November, Huang Hua arranged for me to visit Mao’s headquarters in Yenan, whose approaches were being blockaded by Chiang Kai-shek’s armies. The blockade had been imposed during the war against Japan. One of Stillwell’s complaints about the Generalissimo’s behavior during that war was his practice of diverting troops from operations against the Japanese to blockade his Communist foes in the internal struggle for power. I had no forewarning that I would be in Yenan at a crucial turning point in Chinese Communist relations with the United States.

![]()

2

YENAN

AT MAO ZEDONG’S HEADQUARTERS

I flew to Yenan aboard a rattling old U.S. Air Force C-47 transport, one of the Executive Headquarters’ planes, in a two-and-a-half-hour flight that took us over the Shensi Mountains to the edge of the Gobi Desert. Maneuvering through twisting mountain passes, we bypassed a Tang dynasty pagoda atop a hill and bumped to a hard landing on an airstrip in a narrow valley. Members of the U.S. Army Observer Group, famed as the Dixie Mission, and Chinese officials were on the airstrip to meet this monthly supply aircraft. In a jeep we forded the murky Yen River, a tributary of the Yellow River, and driving into Yenan entered the compound of the U.S. Army Group, where I was to be quartered. The compound had been hollowed out of the adjacent loess hill and was enclosed in an earthen wall. It encompassed a row of cavelike living quarters with a mess hall and a recreation center named after Captain Henry C. Whittlesey, a former member of the Dixie Mission. Whittlesey, a talented writer, had been captured and executed by the Japanese in February 1945 after he and a Chinese photographer entered a town thought to be secure. A Chinese Communist battalion was destroyed in great part when it was deployed against the Japanese in a failed effort to rescue the pair. The remains of the photographer were found in a cave many years later, but not those of Whittlesey. The members of the Dixie Mission, originally eighteen military officers and diplomats, had their living quarters and offices in the cave structures, which were actually tunnels with whitewashed clay walls about eighteen feet long lined with stone blocks and a wooden frame window at the entrance. Light bulbs powered by the compound’s generator dangled from the arched ceiling. Charcoal braziers provided meager heat. The size of the Dixie Mission had been recently cut back to a small number of army liaison officers, and the Chinese were using some of the empty cave dwellings as guest rooms. I was assigned to one of them and slept on a straw mattress resting on wooden planks supported by sawhorses.

The compound fronted on a city in which thousands of people dwelled in small houses on the valley floor while others occupied some ten thousand caves dug out of the hillsides. Once a thriving ancient walled city, Yenan had been almost entirely destroyed in 1938 by Japanese bombing. The Communists brought it back to vibrant life by making it their headquarters, expanding the community with hospitals, a university, a radio station, and a large open wooden amphitheater in which traditional Peking Opera and other performances were staged. Apart from the peasants bringing their produce into the city, everyone on the streets and in the government buildings wore similar padded blue cotton tunics and trousers, and leather-soled sandals or cloth shoes. Unlike in Peking, there were no beggars on the streets. Pausing at the little shops along the streets, I encountered students from every part of China. As many as 100,000 cadres had been trained in the Central Communist Party School in the valley and sent out to organize party cells in the countryside. Evenings I watched the cave dwellers, some twenty thousand of them, mainly workers in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) apparatus, bearing flickering kerosene lanterns—there was no electricity except for that supplied by generators at the American compound or in the hospitals—wend down the hillsides to the wood and stone buildings on the valley floor to attend political meetings and performances by theatrical groups. There was a Saturday night dance at which Mao himself and a mix of officials and ordinary folk would prance to American tunes played by a small string orchestra. Mao, said to be ill, was not at the dance I attended. When the weather was mild, the dances would take place in a grove of trees called the Peach Orchard.

Soon after I arrived in Yenan, I was at a dinner attended by the top leaders, one of whom was Liu Shaoqi, general secretary of the Communist Party, second in power to Mao and Zhu De, commander in chief of the newly organized People’s Liberation Army (PLA), a force then of about a million troops comprising the legendary Eighth Route Army, the New Fourth Army, and the Democratic Forces of Manchuria. Mao Zedong was not there, and my promised interview with him never materialized. I was told that he was ill and under the care of two Russian doctors, Orlov and Melnikov. Members of the Dixie Mission surmised correctly that the doctors were also being used by Mao for liaison to Moscow. Mao also had the medical attention of an American doctor, George Hatem, known to the Chinese as Dr. Ma Haide, with whom I had very useful conversations. Hatem, a personable, dark-eyed man of Lebanese origin who wore the usual cotton clothes except for a black beret, arrived in China during the war against Japan at the age of twenty-three after receiving some medical training in his native Lebanon and Europe and attending pre-med school in the United States. He traveled to Yenan with Edgar Snow, stayed on to work in public health, married a Chinese girl, Zhou Sufei, became a Chinese citizen, and joined the Communist Party. When I met him, he was a senior staff member of the Norman Bethune Memorial Hospital, named after a much celebrated Canadian who journeyed to China in 1938 during the war against Japan and provided medical assistance with meager equipment and supplies to Communist troops at camps in remote areas.

Mao was absent from all the events which I attended. While I was told simply that he was ill, I speculated that he had retreated into isolation, possibly suffering one of his bouts of depression to which he had been subject over many years. It was said that he was most prone to these depressions when his political and military fortunes ebbed. He was living in a small wood and mud-plastered house with his third wife, Jiang Qing, and their eight-year-old daughter, Li Na. I saw Jiang Qing only once. One night there was a performance in the Peking Opera House of yang-ko peasant dances. In the yang-ko—literally the “seedling song dances”—the performers did chain-step folk dances while singing ideological-themed songs. Jiang Qing was there seated in the front row beside Liu Shaoqi, Zhu De, and other members of the Central Committee. I sat in the row behind them. I had seen photographs of Jiang Qing before her marriage to Mao when she was a glamorous, bejeweled movie actress: her hair long, eyebrows penciled thin, and lips heavily rouged. The woman seated beside Liu wore glasses, no makeup, her hair cut in a bob, and she was dressed like the others in a cotton tunic padded against the November chill, baggy trousers, and a black cap. She was chatting gaily and applauding the performance. Although seated with the notables, she was not at the time in the inner circle of political leadership. She was active in Yenan’s cultural life but in the main simply Mao’s attentive housewife. She was restricted to that role by the party leaders, who never quite approved of Mao’s marriage to this woman with a risqué Shanghai past replete with prior marriages and affairs. Recalling that scene in later years, I thought there was far more theater in the front row than on stage. Two decades later, Jiang Qing would become the driving force in the Cultural Revolution and locked in a power struggle with Liu Shaoqi, who was seated at her side on that theatrical evening in Yenan. Their struggle ended for both in turn in imprisonment and ghastly deaths.

Three months prior to my arrival in...