eBook - ePub

Railroads in the Civil War

The Impact of Management on Victory and Defeat

- 275 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

By the time of the Civil War, the railroads had advanced to allow the movement of large numbers of troops even though railways had not yet matured into a truly integrated transportation system. Gaps between lines, incompatible track gauges, and other vexing impediments remained in both the North and South. As John E. Clark explains in this compelling study, the skill with which Union and Confederate war leaders met those problems and utilized the rail system to its fullest potential was an essential ingredient for ultimate victory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Railroads in the Civil War by John E. Clark, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE CHALLENGE OF WAR MANAGEMENT

Union and Confederate Government Responses

In a war for national existence…the whole mass of the nation must be engaged.

—Josiah Gorgas

Neither the Confederacy nor the Union expected a long war, nor could they have anticipated the scale to which it would grow. As its harsh unfolding erased any expectations of a short and glorious war, both Union and Confederate war governments faced the challenges of establishing political, military, and industrial policies. They had to determine their objectives; marshal, prioritize, and allocate scarce resources; and then employ them effectively to achieve the final victory.

They needed the cooperation of their railroads in order to fight a war governed by logistics and mobility. This meant arranging adequate military passenger and freight rates, integrating separately owned and competing railroads, compensating for the war’s drain on skilled manpower, and insulating railroad operations from army interference. The Union and Confederate governments took different paths to meet these challenges. Comparing the Longstreet and 11th and 12th Corps movements demonstrates the success with which each side achieved its goals.

A nation fighting for its existence ignores reality at its peril. As the weaker combatant, the Confederate government had to take bold steps to achieve maximum effectiveness with its war-making resources. Central planning and sound management policies would have provided essential guidance in determining how to win a long fight for independence. Planning would have enabled the Confederate government to assess its needs, identify obstacles to meeting them, and determine the most appropriate solutions. Carefully established priorities would have shown the Confederacy how to husband and allocate its scarce resources. The Confederacy could not satisfy every legitimate need. It had to decide who must have and who could not. It had to establish a system to coordinate and manage the timing of logistics procurement, transportation, and distribution functions. It did none of these things. In spite of having absolute control of all natural and manufacturing resources, the Confederate government never centralized procurement or established priorities for allocating its limited supplies. As a result, it squandered resources essential to its war economy, encouraged wasteful duplication of effort, and promoted destructive competition. The combination proved fatal to a weak combatant fighting a war increasingly dominated by logistics. Frank E. Vandiver describes a Confederacy “wrecked by decentralized centralization.”1

Confederate departments scrambled for materials. Resourceful bureau chiefs hoarded supplies, thus denying them to other agencies in need. In July 1864, for example, Commissary General Northrop learned that Josiah Gorgas’ ordnance officers had bypassed his office and cornered a six-month supply of wheat to feed Ordnance Department personnel. They purchased all they needed by simply ignoring Northrop’s carefully established price schedules.2

The Confederacy believed at the start of the war that geography, specifically its huge size and interior lines of communication, gave it substantial advantages. The total Confederate land mass covered a map of Europe from the Bay of Biscay to east of Moscow. The military concept of interior lines presumes an advantage in an army’s ability to reinforce or concentrate separated units from a central position more rapidly than its enemy; that is, an army can move between two points inside an area faster than an enemy moving around the perimeter, or invading its interior, at comparable speed. Soldiers before the Civil War thought of interior lines in terms of space, or distance, although geography sometimes conferred an additional advantage. The Civil War began to modify the concept, increasingly framing the advantage in terms of time, as railroads and steamboats improved travel speed and freight loads; today’s soldiers call it “superior lateral communications.” The air age has eroded the concept’s significance, though it remains valid for such aspects of logistics planning as bulk cargo shipping.

General Pierre G. T. Beauregard used the Manassas Gap Railroad to shuttle General Joseph E. Johnston’s troops from the Shenandoah Valley to the First Manassas battlefield in July 1861. Enough soldiers arrived just in time to reinforce Beauregard’s army and contribute to winning the war’s first battle. Beauregard’s creative use of railroads, according to Archer Jones, caused a “paranoid Union overestimate of Confederate capacity for strategic troop movements by rail.” The Yankees believed that railroads brought troops from as far away as Mississippi for the Seven Days’ Battles near Richmond in July 1862.3

General Braxton Bragg also demonstrated the strategic value of railroad movements within interior lines. He shipped 31,193 troops from Tupelo, Mississippi, to Chattanooga, Tennessee, to meet a Yankee threat in July 1862. His soldiers linked up with General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry, and the combined forces attacked Union General Don Carlos Buell’s columns advancing toward Chattanooga. They threatened Buell’s extended line of communication along the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad and forced him to retreat. Bragg’s timely movement saved Chattanooga and eastern Tennessee’s invaluable copper and nitre reserves for the Confederacy for another year.

Size of eastern Confederacy compared with western Europe

The Bragg movement, however, revealed the fragility of the interior lines advantage. Union army planners, in order to break the Confederacy’s lines of communication, shrewdly selected rail junctions as primary campaign objectives. They proved the strategy’s soundness when Union General Henry W. Halleck’s army captured the rail junction at Corinth, Mississippi, in May 1862. This blocked Bragg’s most direct route to Chattanooga, 225 rail miles, and forced him to send his army by way of Mobile, Alabama, a 776-mile journey. The first three thousand troops completed the trip in six days over six railroad lines. Bragg’s cavalry, artillery, and other horse-drawn equipment, in contrast, took six exhausting weeks to march overland. Other deficiencies further eroded the advantage. Rail gaps between Meridian, Mississippi, and Selma, Alabama, and between Selma and Montgomery, Alabama, turned the 150-mile distance between Meridian and Montgomery into a 350-mile detour through Mobile, adding two days to the trip.4

The true advantage of interior lines, Robert Black argues, depended on the Confederacy’s ability to exploit it. It had to act decisively to cobble together a railroad system capable of meeting its wartime needs. It had to integrate the railroads by closing critical gaps between them and connecting the same-gauge tracks of different railroad companies in order to exploit the most direct routes and maximize the use of available rolling stock.5 It had to provide adequate maintenance, parts, and equipment by leasing, purchasing, or, if it must, seizing outright or cannibalizing the rails and rolling stock of less critical routes. Lucius B. Northrop, the Confederate commissary general, immediately recognized the need to centralize railroad operations for the efficient collection and distribution of food supplies, as well as to prevent food speculation and “venality.”6 But the Confederacy took none of these steps and overcame none of these challenges.

The antebellum United States government, a deliberately small and loosely organized institution, reflected the pedestrian tempo of peacetime administration. There were 36,106 civilian employees in 1860, 85 percent of whom worked for the Post Office Department. According to James Huston, the army went to war armed with administrative structures “more often the product of tradition and policies and diplomacy and leadership than of clear-cut logic.” The Founding Fathers, however, had designed a government that could grow strong enough to defend itself. In spite of early missteps, the Union achieved the most rapid mobilization in American history. The army expanded by a factor of 62, from 16,000 soldiers in 1861 to 1,000,000 men by 1865 without, Huston notes, the benefit of a National Guard, as in World War I, or a growing army of draftees, as at the beginning of World War II. Federal spending increased from $22,981,000 in 1861 to $1,032,323,000 in 1865.7

In spite of having to overcome problems related to the sheer magnitude of the task, such as rejecting dishonest vendors’ shoddy goods, the United States marshaled its industrial base to destroy the Confederacy, much as it would do to bury three totalitarian regimes in the twentieth century. Tailors created standard sizes to clothe Union soldiers; specialization of labor and sewing machines reduced shirt-making time by a factor of eleven. Wool production tripled, and new manufacturing techniques quadrupled shoe production. Grain and meat packing output soared. The Springfield Arsenal, the earliest example of the “American System of Manufacture,” produced 350,000 rifles a year by the war’s end for less than $12 each.8

An inherent conflict exists between a ferociously independent free-enterprise economy and a democratic free-market government fighting a desperate war. Robert Weber finds this “strikingly brought out” in the relationships of both northern and southern railroad leaders with their respective governments.9 The Davis administration had to mind southerners’ stubborn arrogance, while both his and the Lincoln administration had to overcome resistance and suspicion by businessmen unused, and not amenable, to any kind of governmental regulations or constraints.

Railroad managers’ and businessmen’s attitudes reflected the laissez-faire business culture of the period. The mid-nineteenth century American executive owed his first duty to his company’s best interests. All other obligations came second, including present-day notions of patriotism. John Garrett, president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, for example, evidently subordinated his strong southern sympathies because Union army traffic generated most of the east-west B&O’s wartime revenue. Loyalty to his railroad made Garrett loyal to the Union. Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s depredations to the B&O cooled the passions of many secessionist-leaning Baltimore residents because he threatened the value of their investments in the company’s stock.10

Their companies’ welfare guided both southern and northern businessmen’s conduct. They never lost sight of, or reduced their primary interest in, the bottom line. They rejected the government’s claim to any right to interfere with their private enterprises. Mary DeCredico describes southern business executives’ attitudes as “patriotism for profit.” Their worship of the invisible hand led “ambitious individuals” to enter war production “for selfless and selfish reasons…fully alert to the prospect of personal gain.”11 To blame southern businessmen’s less-than-total cooperation on greed and obstinacy, however, oversimplifies the matter; northern businessmen held precisely the same attitudes. Governmental intrusion into business conduct, such as the Interstate Commerce Commission and the Sherman Antitrust Act, lay a generation in the future. Most businessmen’s familiarity with the federal government began and ended at the post office, federal court, and customs house. Their understanding of government did not include its encroachment into their domains. Federal and Confederate leaders alike shared the attitudes born of the same culture.

The antebellum business mentality, coupled with the railroad leaders’ devotion to their companies’ bottom lines, encouraged behavior that would horrify observers of today’s supposedly modest business ethics. James Guthrie’s Louisville & Nashville Railroad carried on a lively trade between neutral Louisville and Confederate Nashville for months after the war began. Both governments looked the other way. Most L&N freight rolled south to Confederates who needed the goods. President Lincoln abided the activity because he would do nothing to disturb Kentucky’s declared neutrality.12

Lincoln’s patience paid off. On September 3, 1861, Confederate General Leonidas Polk, a West Pointer who became an Episcopal bishop, committed one of the greatest geographic blunders in the history of warfare. Expecting to excite an outpouring of Confederate sympathy, he invaded Columbus, Kentucky. The Confederate “aggression” prompted a quick and powerful Union response. The Yankee counterthrust invigorated the career of a failed drunk named Ulysses S. Grant, adding to the magnitude of Polk’s miscalculation. By violating Kentucky’s neutrality Polk opened what had been an impenetrable Confederate sanctuary. The Cumberland and Tennessee rivers flow from Tennessee through Kentucky to the Ohio River and, with the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, became transportation daggers into the Confederate heartland, as the Yankees quickly demonstrated. They captured Nashville on February 23, 1862. Its significance as the first Confederate state capital to fall pales besides its importance as an industrial city—it produced all the Confederate gunpowder fired at First Manassas. The Yankees’ taking Nashville also ripped the Tennessee breadbasket from the Confederacy. President Lincoln once said that he hoped to have God on his side, but he absolutely had to have Kentucky. It appears that he got both.13

A war for national survival aside, business was business. Fealty to that mind-set produced behavior that many twentieth-century Americans might find bizarre. Northern railroads participating in the 11th and 12th Corps movement, for example, maintained their regular schedules before moving the troop trains. The War Department knew it and, in spite of the mission’s urgency, accepted the practice without question. When asked about the L&N’s capacity to support the movement, General Boyle in Louisville advised Secretary Stanton that “Passenger trains occupy twelve hours between Louisville and Nashville; for trains with troops, about sixteen hours” for the 185-mile trip. The 150th New York spent many idle hours on side tracks, cooking bacon and boiling coffee because they “were not making schedule time.” For this reason, and because of frequent stops for water, according to General Oliver Howard, they “did well to average fifteen [miles per hour].”14

The Civil War, however, demanded entirely new relationships between business and government. The federal government put itself in a position to receive excellent cooperation from the northern railroads throughout the war. Both President Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton had represented railroads as lawyers before the war. They understood the technical sophistication needed to operate these complex systems, and they preferred to leave the railroads in civilian hands.15 Lincoln, as a war president, proved an excellent delegator. No one in America understood more clearly the war’s objective, shared his strategic vision for winning it, or felt deeper anguish about its cost. But he possessed the personal confidence and self-restraint to refrain from meddling and let others do their jobs. During the 11th and 12th Corps movement, for example, he stayed informed, but otherwise kept out of the way.

The northern railroads in 1861 also had a powerful ally in Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott. A former vice president of the Pennsylvania Central Railroad, he argued convincingly that the War Department should leave the northern railroads under civilian management. He made it quite clear to railroad managers, however, that he expected them to act as “direct adjuncts” of the War Department. He also assured them that cooperation served their interests better than otherwise certain coercion.16

Stanton and Scott helped placate the railroads by arranging a uniform shipping rate agreement. The government paid two cents per mile per man for military passengers. A sliding scale covered other government freight based on the type of cargo, weight, and distance. General cargo, for example, cost ten cents per hundred pounds for thirty miles, ninety cents for four hundred miles. A fair, actually generous, arrangement, the accord made good practical business sense. The government gained cost stability, and adequate payments gave the railroads the operating capital they needed to maintain their roads. Quartermaster General Montgomery Meigs later conceded that the government paid premium rates to the railroads but argued that it received outstanding, and therefore economical, rail service during the war.17

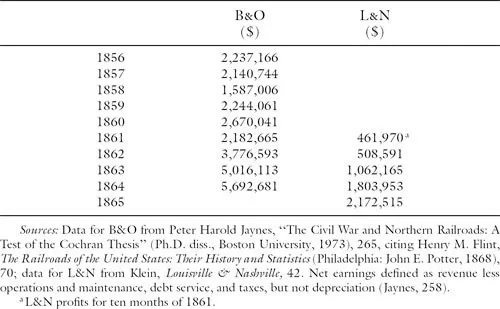

NET EARNINGS OF THE BALTIMORE & OHIO RAILROAD, 1856–1864, AND THE LOUISVILLE & NASHVILLE RAILROAD, 1861–1865

Capitalism measures success at the bottom line. Well-managed northern railroads made money hauling troops at the 2-cent rate; their prewar passenger costs averaged only 1.8 cents per mile. Once the railroads passed the break-even point, large volume guaranteed huge profits to their high-fixed, low-operating-cost businesses. A well-run railroad reached optimum operating efficiency as it approached maximum capacity, as the B&O’s and L&N’s wartime net earnings confirm.18

The magnitude of the B&O’s profits gains in significance when one considers the frequency and enthusiasm with which Confederate soldiers wrecked the road. Stonewall Jackson seized the B&O near Harpers Ferry shortly after the war began and literally held it hostage. When he withdrew in June 1861, he took as much B&O property as he could with him, including 14 locomotives and 36 miles of rails, and smashed an impressive amount of what he could not. His men destroyed 42 locomotives and 386 cars, burned 23 bridges, and pulled down 102 miles of telegraph line. Nine months passed before the B&O restored train service to the Ohio River.19

Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia tore up the B&O during the Antietam and Gettysburg campaigns, an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 The Challenge Of War Management

- 2 The Confederacy

- 3 Southern Railroads And The Longstreet Movement

- 4 “A Serious Disaster”

- 5 The 11Th And 12Th Corps Movement

- 6 The Failure Of Confederate War Management

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index