![]()

Chapter 1

THE STEINHEIL AFFAIR

Sex, Sin, and Murder

Qui culpae ignoscit uni, suadet pluribus.

Syrus, Sententiae, No. 578

I

The Steinheil affair began on a stormy night in May, 1908, with all the trappings of a lurid detective novel: a beautiful woman gagged and bound to her bed, disguises and wigs, a watchdog mysteriously absent, the pendulum of the clock stopped, and two corpses, those of the noted painter Adolphe Steinheil and his mother-in-law, Mme Emilie Japy. Steinheil’s wife, Marguerite, was the woman found tied and gagged, alone able to tell the tale of a night of terror. Tell a tale she did, until she trapped herself in a web of lies and transfixed a fascinated public. The truth seemed impossible to find, and everyone connected with the case stepped onto a slope of conjecture and hypothesis. A bizarre double murder came to be transformed into a celebrated “affair” that passed judgment not merely on Mme Steinheil but on the French judicial process as well.1

Jeanne Marguerite Japy, always known as Meg, was born on April 16, 1869, at Beaumont in the department of Belfort to a wealthy and conservative Protestant family. With her two sisters, Julie and Mimi, and her brother, Julien, she spent the comfortable childhood of a bourgeoise learning to play the piano and gracefully to ride horses. But there were tensions in the family. The Japys had traditionally been hardware manufacturers, and Meg’s father, Edouard Japy, had for a time managed one of the family factories in nearby Montbéliard. After retiring to the country, he became an alcoholic, watching his wealth slip slowly away. His marriage had been a disappointment. As a young man, against the wishes of his family, he had wed a pretty teenaged girl, Emilie Rau, whose parents owned the modest Lion Rouge Inn outside Montbéliard. After a few years had passed, the love in the relationship had gone, but the stigma of mésalliance remained.

Meg was her father’s favorite child, but in 1888 when she was nineteen, she also failed him. She had grown tall and beautiful, her oval face and plump lips alluring, her dark deeply set eyes mysterious and accentuated by the copper chestnut color of her hair, her figure stunning. At the same time, she retained a pouty innocence, a look she would lose only in middle age. There were many suitors, and she fell in love with a handsome lieutenant, Robert Scheffer. He was a friend of her brother, and both were stationed with the Thirty-fifth Infantry at Belfort. Scheffer had every romantic virtue but no money. Meg’s father became apoplectic when he learned that the initial interest had by the late fall of 1888 turned into a love affair. Remembering the reaction of his parents to his own marriage and the increasingly precarious state of the Japy finances, he forbade his daughter to enter into this mésalliance and for her sins sent her into quasi exile to the home of her married sister Julie in Bayonne. A few days later on November 14, he raged himself into the heart attack that caused his death.

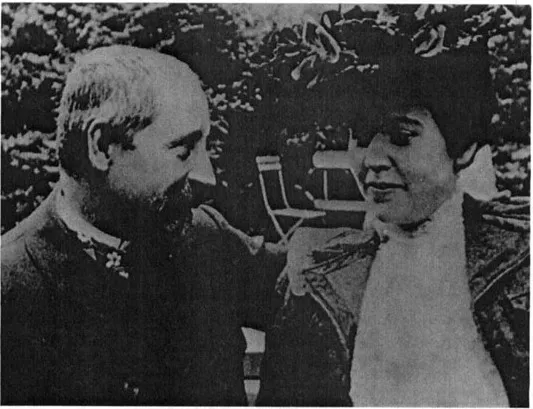

Adolphe Steinheil and his beautiful young wife, Meg

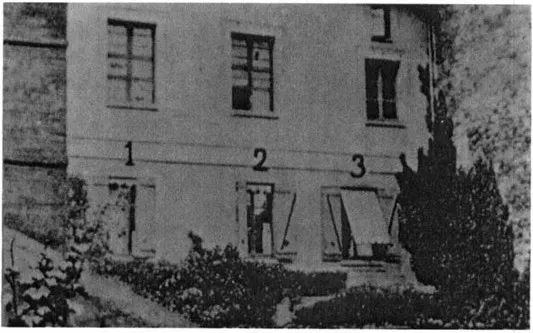

The house in the Impasse Ronsin in which Meg Steinheil was found bound and gagged (window 3), with her husband and her mother dead in adjoining rooms (windows 1 and 2)

The headlines announcing Meg Steinheil’s acquittal, with photographs of Meg and her attorney, Antony Aubin

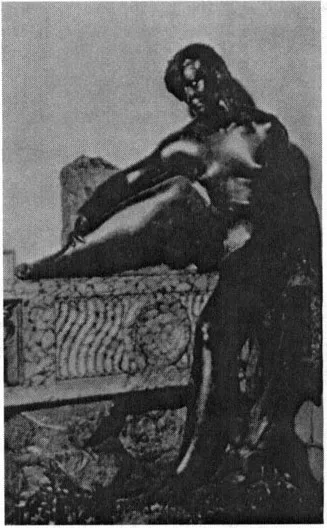

In her youth, Meg Steinheil posed for this statue by Jean Hugues, which is now in the Palais du Luxembourg, where the French Senate meets.

Meg was now out of sight, but her romantic indiscretions with Lieutenant Scheffer had been noticed. They fueled the additional rumors that hang like an albatross in conservative society about the neck of a girl who seems errant and wild. There was talk of an earlier affair with the son of a grocer and even of a bastard son. It made little difference that these stories were inventions without substance: Meg’s value in the marriage market had plummeted.

Suddenly widowed and her daughter a scandal, Emilie Japy was delighted to find what seemed to be a relatively painless means of alleviating a portion of her embarrassment. At Bayonne, Meg had been introduced to Adolphe Steinheil, a Parisian artist working on frescoes and stained-glass windows in the cathedral. Odd-looking with his large moustache overpowering a weak face and small eyes, forty years old, self-effacing, he was hardly the stereotype of the nineteenth-century profligate artist. For one of the few times in his life, this gentle and timid man succumbed to emotion. He fell helplessly in love with the beautiful young Meg and pressed his suit by offering her lessons in painting. At first, neither mother nor daughter found this attention attractive, but Mme Japy grew much less hostile when she learned that Steinheil had an excellent artistic reputation—derived largely from an association with his father, Louis Steinheil, who had restored the windows of the cathedral at Chartres and of the Sainte Chapelle, and from his uncle, Jean Louis Meissonier. In the 1950s the sculptor Constantin Brancusi would recall, “In Steinheil’s time, he was something like what Bernard Buffet is today.” Meg was brought around to appreciate the painter by the thought of living in Paris. Steinheil lacked a fortune and he was a Catholic, but here was an opportunity to marry Meg off before she found another romantic but unacceptable suitor. The marriage was arranged, and after a proper period of mourning for Edouard Japy, it took place on July 6, 1890.

After an Italian honeymoon, the Steinheil ménage moved into the artist’s large house at 6 bis Impasse Ronsin, in the Vaugirard district (15e arrondissement) of left-bank Paris. There was an enormous amount of room in the four storeys, and the house easily served as both a residence and a studio for Steinheil. Meg became pregnant almost immediately, and in June, 1891, she gave birth to her only child, Marthe. Nevertheless, the marriage failed from the beginning. The allure of being the wife of an artist disappeared before the reality of being the wife of this artist, the very opposite of a man of the world, unexciting, unambitious, too much like his canvases, which were praised more for their careful and precise technique than for their originality. He was twenty years her senior and content that each year since 1870 the official state exhibition had selected one his paintings for hanging, content to lead a mediocre existence on a minimum income: no new clothes, no new furniture, no new anything. Most serious, he also had homosexual tendencies, leading Jules Roche, the Progressive politician, to remark cruelly, “This shifty Steinheil prefers to look at men from the rear than face to face.”2

Bored by her life and frustrated at her inability to play the role she had envisioned for herself, Meg soon sought the satisfaction of her dreams outside her marriage. In 1893, she took a state prosecutor, Manuel Baudouin, as her first lover. Like others later, he would be fascinated by the combination of her availability and her schoolgirl appearance; like them he would be alternately attracted and repelled by the lack of passion in her embrace and the calculation and innocence that coexisted in her eyes. She could be both virgin child and serpent. Baudouin was amazed at how easily she accounted to Steinheil for her long absences and for the gifts he showered on her during their four-year liaison. She invented the story of an “Aunt Lily,” the natural sister of one of her cousins, claiming to have reunited them and to pay visits to Aunt Lily, who gave her jewels and knickknacks in gratitude. This excuse was pathetically transparent, and Steinheil was aware of her infidelity very early. He allowed it to continue and even agreed to live with Meg at the Impasse Ronsin as brother and sister because he remained profoundly in love with her and feared losing his daughter if he insisted on a divorce. There was also a less elevated reason to feign indifference. To bring additional money into the household, Meg badgered the prosecutor, and later his successors to her favors, into posing for portraits by her husband, thereby providing a steady source of income.

Upon the departure of this first lover in 1897, Meg was ready for a liaison of higher status and set out to win the ardor of Félix Faure, the newly elected president of the Republic who had always cut a wide swath through the ladies. Faure had met both Steinheils at receptions in 1894, when he was as yet only minister of the navy. As president after 1895, he was immensely more attractive and also had within his gift the commission of great tableaux for the state. He found Meg’s allure irresistible; Meg delighted in pretending to be a republican Pompadour. Steinheil’s reward was the appointment to produce the mammoth Remise des décorations par le Président de la République aux survivants de la Redoute Ruinée (8 août 1897) of 1898, for which he was paid thirty thousand francs and created a knight of the Legion of Honor.

Meg began almost daily visits to the Elysée palace, entering by a small door in the gardens at the comer of the Rue du Colisée and the Avenue des Champs Elysées. In her memoirs, she would claim that these visits were to help Faure with the composition of his memoirs and to carry out secret errands for him. The secret errands were essentially a single one, to wait for him in the Blue Salon of the palace as his chief mistress, a fact known by many in fashionable Paris. It was in this capacity that she provoked his death of stroke and heart failure on February 16, 1899, at the height of the Dreyfus affair. Louis Le Gall, the secretary of the Elysée, discovered her beneath Faure, naked in his arms, helpless as he clutched her hair in his struggle for a last breath. Hastily summoned palace domestics desperately prized her loose and rushed her out half-dressed—without her corset—as a priest was led in from the street in a vain effort to hear Faure’s confession. During the next two weeks, several of the more sensationalist newspapers accused a certain Mme S——of knowing a great deal about the death of the president and of carrying off undisclosed papers from his office. The government had hushed up her role in the business, and Meg found no grounds for suit since she was not named explicitly by the press. The insinuation about purloined papers had no basis in fact and no consequences except to inspire Meg’s later comment in her memoirs.3

From the early 1890s to 1908, Meg conducted a weekly salon at the Impasse Ronsin, entertaining three to four hundred people during the course of an afternoon in her spacious drawing room. Her goal was to heighten the appreciation of Parisian society for Steinheil’s paintings and thus to bring him more sales, although it is doubtful that the increased income much more than covered her expenses. Steinheil refused to hawk his wares so blatantly and found the salon embarrassing. He was also aware that whatever the avowed purpose of these afternoons, Meg was the main attraction. Pretty, seductive, an excellent musician, receiving with exquisite grace, she attracted all of artistic, literary, and eventually political Paris. François Coppée (poet), Pierre Loti (novelist), Auguste Bartholdi (sculptor), Charles François Gounod (composer), Ferdinand de Lesseps (of the Suez canal), Emile Zola (novelist), Léon Bonnat (portraitist), Jules Emile Massenet (composer), Camille Groult (art collector), François Sadi-Carnot (deputy, minister, president of the Republic), Jules Méline (deputy and premier), Admiral Alfred Gervais (of the Kronstadt mission), Hippolyte-François Alfred Chauchard (founder of the Louvre stores), nobility and diplomats from several countries, cabinet ministers, and even the Prince of Wales crowded into her salon. Some repaid her hospitality by purchasing the period studies that were Steinheil’s speciality. Some became the lovers of this woman whose code of morality was so singular for one of her position and later commissioned portraits and other subjects from her husband. In such fashion, the household sought to meet expenses: Meg offering her delectable charms for sale, with the coin of purchase a canvas from Steinheil’s studio.

The artist occasionally bemoaned his existence as perpetual cuckold to his brothers-in-law and to a few other friends, particularly several of his longtime male models. For the most part, he had come to terms with this life in which Meg was his wife in legal fashion only. He tolerated all of her lovers, whether those who bought her favors once with a single purchase or those whose attentions lasted longer and thus were more lucrative to his brush. By 1905, however, it was doubtful that this arrangement could last much longer. Steinheil himself was fifty-five and no longer able to work consistently because a habit of taking opium at night to aid sleep had caused him to age prematurely. He produced fewer canvases each year, and income from sales declined proportionately. Meg was now in her mid-thirties. She remained a stunningly beautiful woman—described by Gustave Téry as a madonna by Andrea del Sarto—who could be mistaken easily for her daughter’s elder sister, but she could not hope to attract wealthy lovers for very many more years. There was also the question of Marthe, who was now in adolescence. Although she knew nothing of her parents’ lives apart, this secret could not be kept from her forever.4

Meg’s lovers had always been replacements for Steinheil, but up to this point, they had served principally to satisfy her mythomania, her delusions of prestige, wealth, and, not incidentally, dominance over men. In choosing to compromise herself, she placed them in her thrall while she remained untouched emotionally. Now, there was an increasingly pressing need of a permanent substitute for Steinheil. In early 1905, she met Emile Chouanard, director of the Forges de Vulcain, very wealthy, about forty years old, a man who never allowed guilt to interfere with his pleasures. In the beginning, he was willing to play the game of purchasing paintings from Steinheil and meeting Meg in hotel rooms to carry on an affair. After a few months, he tired of this and proposed that Meg rent a hideaway where they might meet at leisure and offered to pay whatever bills for it that Meg presented to him. From this suggestion came the acquisition of a villa, the Vert-Logis, outside Paris overlooking the Seine in the small town of Bellevue. The location was convenient—only forty-five minutes away by train from both the Montparnasse and Invalides stations—and Meg arranged to rent the villa in the name of one of her friends, Mme Mathilde Prévost, who lived near the Impasse Ronsin at 10 Boulevard Edgar-Quinet. To take charge of the housekeeping, she had her trusted chambermaid, Mariette Wolff. Steinheil made no objection to this arrangement except to insist that he be welcome at Bellevue when Meg did not have other male visitors. To the curious, both husband and wife explained that Meg’s trips to the villa were to meet her Aunt Lily.

Chouanard was very generous with his money, paying the entire cost of the villa at Bellevue and many of Meg’s other bills as well. Meg may have entertained some hopes of marrying him eventually, but in November, 1907, the affair came to an end. The specific incident was a dispute over Chouanard’s choice for his daughter’s fiancé, but the larger issue was Meg’s presumption in claiming to interfere in Chouanard’s family concerns. She was, after all, only a mistress, and the affair had run its course after more than two years.

Perhaps Meg was disconsolate; surely she was disappointed. These emotions may have contributed to a fainting episode that occurred while she was riding the Métro a few weeks later in December. Or perhaps it was Meg the actress. An elegant young nobleman with a gold-headed cane, Count Emmanuel de Balincourt, walked her home, and by the time they reached the Impasse Ronsin, Meg had decided to make him her next conquest. Balincourt was handsome and appeared wealthier than he was. Meg invited him to dine at the Impasse Ronsin and to see her husband’s paintings. He paid the visit, spoke at length with Steinheil about art, and found the artist sympathetic. He commissioned a portrait in riding habit. A week later, he traveled to Bellevue for a tryst with Meg and then was overwhelmed with guilt. He finished the poses for his portrait and bought two other canvases as if in private amends. He did not see Meg again.

These experiences left Meg desperate. She was now thirty-eight years old and could not expect to find many more Chouanards or Balin-courts. This sense of despair made her all the more delighted when she met Maurice Borderel on February 15, 1908. He was nearly fifty years old and a recent widower with three adolescent children, a son and two daughters. Tall, pot-bellied, and bald, with a blond beard and russet moustache, a rustic from the Ardennes, gentle, but for all that a wealthy landowner, his emotions were not a match for the supreme Parisienne. He succumbed to Meg almost immediately and paid his first visit to the villa on March 6. Like Chouanard, he paid her debts. Unlike him, he fell in love. From the start, he insisted that he could not marry her. He would not disgrace the memory of his first wife by taking a divorced woman as his second. Neither did he intend to impose a stepmother on his children. In perhaps ten years’ time, when his children would be grown and married, if Meg had been freed by Steinheil’s death, they could then discuss the matter of marriage. Even under these conditions, there were to be no promises, no certainties.5

It is easy to imagine how Meg felt. Borderel seemed her last chance to win a new husband while she was still young. He had made his intentions clear, but he was in love with her and kept returning to the villa ever more entranced. His mind could be changed. Everything was still possible if only Steinheil were not an obstacle. Divorce could not be considered, because neither would surrender Marthe and because Borderel would be very reluctant to marry a divorcée. Steinheil would have to die. And die he did, along with Meg’s mother, on the night of May 30–31, 1908.

Sunday, May 31, was Pentecost, the day of the derby, extremely hot and uncomfortable. At 6 A.M., the Steinheil valet, Rémy Couillard, came sleepily down the stairs from his room in the fourth-floor attic to hear moans from the bedroom on the second floor where Marthe usually slept. But Marthe was at the villa in Bellevue, where Steinheil, Meg, and Mme Japy, who had arrived two days earlier for a visit, were to join her that afternoon. Racing into the room, Couillard found Meg tied hand and foot to Marthe’s bed, her nightgown—he was to say—pulled up about her face, leaving her body naked. Beside her head lay what appeared to be a wad of cotton wool that she had finally managed to force from her mouth. She cried out something about robbers in the house and that Rémy should call for help. These words were all that an already jumpy twenty-year-old boy needed to make him throw open a window and scream.

The Steinheil house was located quite near a printing shop on the Impasse Ronsin, and a night watchman heard the cries. He ran to investigate. So did a neighbor, Maurice Lecoq, and a policeman just coming off duty, Agent Ponti. They found the iron gate to the yard open and the outside door to the house unlocked. Alerted by Couillard’s screams, they warily looked for intruders on the ground floor of the house and then rushed up to the second floor. There, they found a frantic Couillard trying to untie the knots binding Meg, who seemed in shock. Stepping into the next rooms, they discovered the bodies of Adolphe Steinheil and Emilie Japy. Steinheil was on the floor of one adjoining bedroom, his legs curled beneath him; Mme Japy was in the bed of the other. Ordinary household cord was wrapped about their necks, and both appeared to have been strangled. Within minutes, a police commissioner, M. Buchotte, and his men had been summoned, and the search for the murderers began.

It was a strange tale that Meg told, the words coming in a rush as though she had been severely traumatized by her experience. She had been awakened about midnight from a deep sleep by the touch of a cloth on her face. She sat up in bed and saw dim figures and shrouded lanterns. Immediately, three men and a woman threw themselves upon her, the woman wielding a revolver. They seemed to take her for her daughter, because the woman hissed: “Your father has sold some paintings, no? Where is the money? No tricks! Or we’ll have your skin, slut!” One of the men said quickly, “We don’t kill brats!” Meg told them that the money was kept in a small study off from the bedrooms, felt herself struck on the head, and then fainted, waking only much later to find herself tied and gagged. After what seemed like hours of effort, she had finally dislodged the gag from her mouth and had begun calling for Couillard, who heard her only when he came down from the attic. Before she fainted, however, she managed to see glimpses of the intruders: the men wore long, black shirts or coats, the woman had brilliant red hair.

Around 9 A.M., Octave Hamard, the...