![]()

· 1 ·

A BRIEF MOMENT OF STABILITY

After traveling through the backcountry South in the early 1840s, the Mississippi historian and editor J. F. H. Claiborne described some of the subtle differences between the plantation and piney-woods regions of southwestern Mississippi. Finding it unnecessary to provide details on the evident contrasts of life in each section, Claiborne instead focused on less obvious yet significant differences, such as foods consumed and leisure activities pursued. In one instance he contrasted the “glorious supper” of oysters, chicken salad, turkeys, terrapin, and champagne he received in Wilkinson County, in the lower Mississippi delta, with a meal he was given in the piney woods. The latter, though abundant according to Claiborne, contained numerous dishes all composed of potatoes prepared in a variety of ways. He and his companion feasted on baked potatoes, fried potatoes, bacon and potatoes boiled together, a hash of wild turkey garnished with potatoes, potato biscuit, potato-based coffee (“strong and well flavored”), and, finally, potato pie and a tumbler of potato beer.1 Claiborne appeared to prefer the finer dining found in Wilkinson County. As with many travelers in the rural South, he found the relative splendor of the plantation setting and the delicacies provided there overshadowed the comfortable but seemingly bland existence of the plain folk. Nonetheless, his observations provide important evidence concerning conditions in the antebellum rural South. The amount and quality of foods consumed indicate that in the late antebellum period prosperous times prevailed in both the plantation and piney-woods regions. Although the nature of the foods in each area differed, sustenance was abundant and in keeping with local crops and conditions.

The term prosperity often appears in conjunction with the term stability when historians discuss conditions in the antebellum South. In 1852, the region of the Florida parishes and environs was highly stable—a stability that resulted from economic prosperity and a corresponding mutual dependence existing between planters and plain folk. Shared interests based on similar agricultural pursuits and on political fears allowed for the prevailing, if temporary, conditions in the Florida parishes. Such a beneficial state of affairs is of particular significance, not only because it contributed directly to the secession appeal, but also because stability had proven inconsistent with the pattern of development in the Florida parishes.

Early instability resulted from the curious history of the area, which had passed from French to British to Spanish hands, placing different and opposing ethnic groups in the territory, many with conflicting land claims. Scores of army deserters and criminal elements exploited the absence of stable government, settled in the area, and exacerbated the prevailing instability. The successful introduction of a cotton-based economy, however, promoted prosperity and stability under the direction of the slaveholding elite. Shared agricultural pursuits, increasing prosperity, and, most important, the bond of slaveholding encouraged the plain folk to defer to the leadership of the planters. The planters nevertheless soon translated leadership into uncompromising power. By establishing themselves as the principal source for purchasing and processing the goods of the plain folk and by securing control of the means of access to market, the planters manipulated the economy to entrench their dominance.

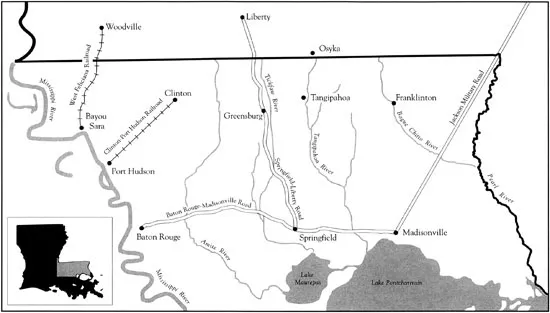

Initial French efforts to colonize West Florida ended abruptly in 1763 with France’s defeat at the hands of Britain in the French and Indian War. In 1764, British troops occupied the fort at Baton Rouge and established additional fortifications just to the south at Fort Bute on Bayou Manchac and to the north on Thompson’s Creek in the Feliciana district. In an effort to solidify their control of the territory, the British offered liberal land grants to retired soldiers. Officers received from three thousand to five thousand acres, while privates could claim up to three hundred acres. The beneficiaries of this land policy, supplemented by British Loyalists who migrated from the Atlantic Seaboard to the Florida parishes during the American Revolution, planted a strong pro-British element among the few scattered French settlers remaining in the area.2

Despite intensive colonization efforts, British control constituted only a brief interlude. In 1779, Spanish forces, under the direction of the governor of the Orleans Territory Bernardo de Gálvez, seized West Florida from the British in a military expedition designed to support the American revolutionaries. The new Spanish overlords graciously allowed the British to remain, with their land claims intact, provided they swore loyalty to the Spanish Crown and embraced Catholicism. These conditions, for some, proved a bitter pill, but the dismal prospect of losing one’s homestead and being uprooted induced many to swallow the pill so as to stay.3

Like their British predecessors, the Spanish also offered large tracts of land to those who would settle in West Florida. In many cases, though, the Spanish grants conflicted with or overlapped the earlier British grants, which Spain had promised to honor. Further complicating the situation, both the British and Spanish grants were almost always vague and confusing. Illustrative of the imprecision inherent in the British titles is a 1776 grant on the Amite River: “Elihu Bay receives all that tract of land situated on the east side of the River Amit [sic] about four miles back from said river upon a creek called the Three Creeks butting and bounding southwesterly unto land surveyed out to Joseph Blackwell and on all other sides by vacant land.” Similarly, an 1804 Spanish grant proclaimed that “Luke Collins claims four hundred superficial arpents nine leagues up the east bank of the Tickfaw River, bounded on one side by William George and by public land on the other two.” Disputed land claims created tension between pro-British and pro-Spanish factions in West Florida.4

From the outset the Spanish government appeared weak and corrupt to the inhabitants of West Florida. Not only did the Spanish make little, if any, effort to resolve the conflicting land claims, but they also failed to appoint district courts to deal with growing criminal activity in the territory. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, large numbers of Americans, encouraged by the United States’ claim to the region presumed in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, augmented the smattering of French and Isleño settlers migrating to West Florida. Many army deserters and criminals were among these Americans seeking a safe haven in West Florida. The territory quickly became infested with undesirables who disrupted settlement patterns and waylaid wagons and travelers on the trails and highways. In addition, considerable numbers of American filibusters, adventurers inciting revolution in Spanish-held areas, were also counted among these migrants. Spanish inability to control marauding, to resolve internal disputes, or to control seditious elements created a volatile mix in West Florida. Official communications and settler petitions demonstrate that a perception of neglect and vulnerability promoted a general feeling of discontent among the population.5 Napoleon Bonaparte’s manipulation of the Spanish Crown further exemplified Spain’s weakness, heightening the belief among some elements that Spain could never adequately police and promote the territory.

An abortive attempt to overthrow Spanish control and to bring stability to West Florida in 1804 originated with Reuben Kemper of Pinckneyville, Mississippi, and his brothers. The Kempers, like many of their neighbors just across the border in the Mississippi Territory, acted to secure their property rights in West Florida out of a belief that increasing instability in West Florida could eventually destabilize their own region. The brief Kemper Rebellion failed because its leaders miscalculated the strength of pro-French, pro-British, and pro-Spanish elements, all of whom felt threatened by the pro-American faction the Kempers represented.6

By 1810, virtual chaos prevailed in West Florida. Spanish authority rarely extended beyond the fort at Baton Rouge and the nearby river towns of Bayou Sara and St. Francisville. Rising criminal activity in the absence of district courts and increasing turmoil resulting from disputed land claims propelled the territory to the brink of anarchy. The chaotic conditions intensified as increasing numbers of army deserters and other fugitives exploited West Florida’s weakness, settled in the eastern parishes, and added to the factional tension. William C. C. Claiborne, who would later become the first American governor of Louisiana, observed that many desirables were coming to the territory but added that “among them are many adventurers of desperate fortunes and characters.” By the fall of 1810, contempt for the ineffectiveness of the “pukes,” a derogatory name applied to Spanish officials, exploded in the West Florida Rebellion.7

Calls for armed rebellion came from large numbers of American settlers, concentrated primarily in the Feliciana district, and others contemptuous of Spanish authority. Following a surprise raid that led to the capture of the fort at Baton Rouge, the rebels moved rapidly to consolidate their control of West Florida. Two groups of citizen militia forming in support of the Spanish in the Springfield and Tangipahoa areas dispersed before rebel contingents arrived. Their hasty retreat allowed the rebels to proclaim the territory independent. The Republic of West Florida endured for seventy-four days before its president, Fulwar Skipwith, reluctantly allowed William C. C. Claiborne to take control of the territory for the United States.

American control, however, failed to bring immediate stability to West Florida. Claiborne reorganized the territory into four parishes but neglected to address aggressively the disorder in the less populated eastern region. He defended his failure to appoint judges for the two eastern parishes, St. Helena and St. Tammany, by arguing that “there is in that quarter a great scarcity of talent, and the number of virtuous men (I fear) is not as great as I could wish.” The state legislature intensified the chaotic conditions in the Florida parishes by delaying six years before moving to organize the judicial system effectively there. Additionally, the new American officials aggravated the dispute over land claims by conferring a blanket recognition of existing claims while issuing new land grants themselves.8

Moreover, the seemingly ambiguous status of the territory created further problems. An 1811 bill providing for the attachment of West Florida to the Mississippi Territory failed in Congress. When in the same year Congress made provisions to admit the Orleans Territory as a state without including West Florida, rebellion flared anew. On March 11, 1811, rebellious elements again raised the lone star flag of the West Florida Republic, forcing Claiborne to dispatch troops to enforce his authority. On April 12, 1812, Congress admitted Louisiana to the Union. Nearly four months later, on August 4, 1812, the state assented to the inclusion of West Florida, from the Mississippi to the Pearl River, as part of the new state.9

Despite lingering legal problems concerning the status of West Florida, statehood introduced a degree of territorial certainty but not internal stability in the Florida parishes.10 Disputed land claims, resulting from the conflicting grants of the various governing powers, continued to create difficulties. As late as 1844 the state legislature implored Congress to resolve the disputed land claims that persisted in impeding settlement. The primary problem, however, continued to lie with the people themselves. Composed of various antagonistic ethnic groups, many containing hostile internal social and political factions, the Florida parishes constituted a volatile melting pot. Lingering British, French, and Spanish loyalties, coupled with land disputes and rampant criminal activity, inhibited the establishment of an effective American system of justice. Addressing Congress concerning complaints he had received regarding the turbulent conditions in the Florida parishes, Governor Claiborne asserted that “civil authority has become weak and lax in West Florida particularly in the parish of St. Tammany in which the influence of laws is scarcely felt.”11 Claiborne’s dilemma seemed compounded by his awareness that many of the residents came to the territory specifically because no effective legal authority existed there. These migrants aggressively resisted the implementation of American authority.

Regional patterns of settlement illustrate the significance of the continuing disorder in the Florida parishes. Although the number of settlers coming to West Florida increased significantly in the first fifteen years of the nineteenth century, the population remained relatively sparse. By contrast, in the Mississippi Territory, the counties bordering the Florida parishes typically contained populations three or four times the number in West Florida. Likewise, the parishes to the west and south had considerably larger populations. These regions, particularly the southwestern counties of Mississippi, had benefited from the disorder in West Florida. Many planters, such as William Dunbar, removed their operations from West Florida to southwestern Mississippi either to avoid the instability and legal confusion prevailing in West Florida or simply to live in territory under American control.12 Since the Florida parishes comprised the area just north of the largest market in the South and possessed soil and natural resources very similar to those in the adjacent counties in the Mississippi Territory, clearly the region’s instability served to inhibit settlement. This situation continued until the 1830s, when an intricate combination of politics and economics ushered in a new era in West Florida. The virgin pine forests, numerous clear running streams, and the expanding and increasingly profitable market for staple crops virtually necessitated the advent of stability in the Florida parishes. Agricultural prosperity, coupled with the introduction of the political dominance of delta planters, led to a state of equilibrium in West Florida.

The residents’ seeming inability to find a profitable crop in the first decades of development retarded progress in the Florida parishes nearly as much as did territorial instability. French, British, and Spanish efforts to promote tobacco and indigo farming proved at best marginally successful. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, however, good fortune finally arrived for the delta planters of West Florida. Facing financial ruin as a result of their failure to market tobacco and indigo profitably, they turned to cotton. The introduction of the cotton gin into the lower Mississippi valley around the turn of the century stimulated this transformation. Planters in the Feliciana district and East Baton Rouge experimented with an upland cotton of the Siamese black seed variety, which proved adaptable to the Louisiana environment. Fortunately for these planters, the slave rebellion in Saint Domingue, occurring at virtually the same time, deprived European manufacturers of one of their principal sources of the fiber. Cotton prices skyrocketed to unprecedented levels, creating an economic boom for the emerging cotton planters of West Florida. By the 1830s, the delta region of Louisiana and Mississippi had surpassed Georgia and South Carolina in the production of cotton.13

Major Waterways, Highways, and Railroads in the Florida Parishes, ca. 1852

High prices encouraged the expansion of the cotton economy, but the piney woods of the eastern Florida parishes appeared unfit for cotton farming. Typically, the piney-woods regions of the Gulf South contained a sandy soil, deposited when the area comprised a part of the Gulf of Mexico. Moreover, pine needles, unlike the remains of rotting hardwood leaves, did not produce the deep, rich, loessial covering above the soil conducive to intensive farming. The eastern parishes, though, like most of Louisiana and southwestern Mississippi, contained numerous rivers and streams. By the late 1830s, industrious farmers had demonstrated that cotton could be profitably raised in the river bottoms and creek beds of the piney woods.14

The introduction of successful commercial agricultural pursuits in the piney woods encouraged farmers in the Florida parishes to experiment with crops other than cotton. Rice cultivation began as early as the second decade of the nineteenth century. By the middle of the 1830s, enterprising farmers demonstrated that the marshland along the north shore of Lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain, as well as the abundant swampland along the Pearl, Amite, and other rivers, proved conducive to rice farming. Rice required minimal capital in its cultivation, making it a viable alternative crop for middling and poorer farmers. By 1840, rice farming constituted a popular and profitable business in the eastern Florida parishes, as well as in the southwestern counties of Mississippi. Amite and Pike Counties in Mississippi, for instance, each produced about 150,000 pounds of rice annually. Marion, Hancock, and Wilkinson Counties also cultivated rice, though to a far lesser extent. Despite the presence of a few sugarcane fields, located primarily in East Baton Rouge Parish, the Florida parishes remained outside the sugar-producing region.15

The pattern of growing cotton along fertile stream beds and rice in swampland continued in the piney-woods parishes through the end of the antebellum period. A 3 percent sample survey of farmers gathered from the 1850 and 1860 census returns demonstrates the significance of staple-crop farming in the piney woods. In 1850, 36.6 percent of farmers produced rice while 48.3 percent grew cotton. Ten years later, though only 20.0 percent continued to raise rice, cotton production had soared, involving 72.2 percent of piney-woods farmers. The increasing emphasis on cotton reflects the rising profitability and expanding availability of machinery to process that staple. Table 2, based on the 3 percent census sample, demonstrates aggregate totals of cotton and rice production in t...