![]()

Chapter 1

Boom

Cities

I

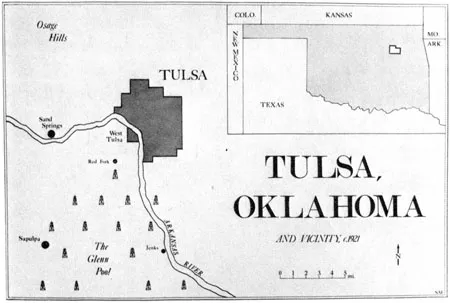

Tulsa was a boom city in a boom state. Between 1890 and 1920, the population of the land which became the state of Oklahoma increased seven and one-half times; the total population in 1920 was over two million. Thirteen other states and territories, primarily in the West, more than doubled their populations during this period, but Oklahoma’s rate of increase was by far the largest. And of these states, only Texas, with its much larger land area, surpassed Oklahoma in the number of people added to her population during these decades. By far, the greater part of Oklahoma’s population boom was due to immigration. But unlike the forced immigration of Native Americans which began in the 1830s, the new immigrants’ move was a matter of choice. Most of them came between 1890 and 1910, an era marked by land runs and statehood (1907).1 They came for a variety of reasons and from a variety of places, but for many Oklahoma was a place to start life anew.

Tulsa’s growth during the first years of the twentieth century was even more dramatic. Located along a bend in the Arkansas River in a verdant area where the oak-laden foothills of the Ozarks slowly melt westward into the treeless Great Plains, it had been a Creek settlement known as “Tulsey Town” during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The first permanent white settlers did not arrive until the early 1880s; Tulsa’s population in 1900 was estimated at 1,390. During the next two decades, the city’s population skyrocketed. In 1910, the Census Bureau listed Tulsa’s population at 18,182; in 1920 at 72,075. In that latter census, Tulsa ranked as the ninety-seventh largest city in the United States, comparable in size to such cities as San Diego; Wichita; Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania; and Troy, New York. City directory estimates, it should be added, were higher than those of the federal government, and the 1921 directory recorded Tulsa’s population as 98,874.2

The primary reason for Tulsa’s rapid growth was oil, and as one writer in the 1920s remarked, “the story of Tulsa is the story of oil.” Petroleum had been discovered in 1897 near Bartlesville, Indian Territory, some fifty miles north of Tulsa, and in 1901 the Southwest oil boom seriously got under way with two noted petroleum discoveries: the Spindletop strike near Beaumont, Texas; and the strike at Red Fork, Indian Territory.3

The hamlet of Red Fork was located directly across the Arkansas River from Tulsa, and its strike was an important early contributor to the city’s growth. Tulsa had been incorporated only three years prior to the Red Fork gusher, and had but few characteristics to distinguish it from other towns in the northeastern part of the territory. It had, however, a hotel of some form as early as 1882, and a local Commercial Club, established in 1902, raised enough money to convince officials of the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railroad that their line should pass through Tulsa in 1903. A year later, three entrepreneurs opened a toll bridge which they had constructed across the Arkansas River, thus making the Red Fork field more accessible to the business and laboring communities in Tulsa.4

Tulsa was growing, but the event which ushered in the city’s most spectacular growth did not come until 1905. In the fall of that year, the Ida Glenn No. 1 oil well gushed some fourteen miles from Tulsa. The area near Sapulpa where the strike was made became known as the Glenn Pool, considered to be “the richest small oil field in the world.” A veritable forest of derricks was constructed in the area during the next two years, and from some of Glenn Pool’s five hundred producing wells flowed more than two thousand barrels of oil per day. Other big oil discoveries followed that of Glenn Pool, and by 1907, the year of statehood, Oklahoma led the nation in oil production. Six years later, Oklahoma was producing one-quarter of all the oil produced in the nation, and by 1915, the young state was producing up to 300,000 barrels of oil per day.

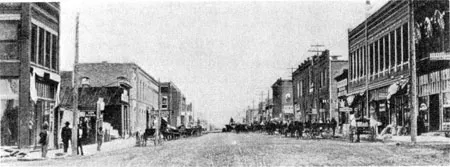

First Street, Tulsa, Indian Territory; probably just after the turn of the century.

Courtesy of McFarlin Library University of Tulsa

Oklahoma rode on top of its oil boom, and Tulsa more and more became the city associated with the boom, the oil industry, and the vast Mid-Continent oil field. After Glenn Pool, the face of Tulsa changed rapidly. A five-story brick hotel with over five hundred rooms was completed one year after the celebrated oil strike of 1905, and civic leaders promoted a “special train called the ‘Coal Oil Johnny’ which pulled about fifteen coaches, leaving Tulsa in the morning, letting the workers off at the various oil fields in the area, and picking them up in the evening for the return trip to Tulsa.”6 Homes were built to accommodate the city’s booming population, and a respectable business district was established downtown. The 1909 Tulsa city directory listed no fewer than 126 oil companies with offices in Tulsa. Two years earlier, the city’s first oil refinery had been built.7 Not only was Tulsa a city where the financial and exploratory ends of a booming oil industry were directed, but it soon became a production and oil well supply center as well. The city also became an important commercial center tied to the state’s agricultural industry, which claimed in 1920 about one-half of Oklahoma’s work force.8 “Tulsey Town” had grown into one of the South-west’s largest cities in practically no time at all. Local boosters called it the “Magic City.”9

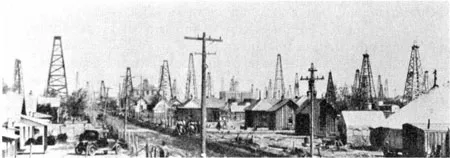

A Scene in the Glenn Pool, south of the city

Courtesy of McFarlin Library University of Tulsa

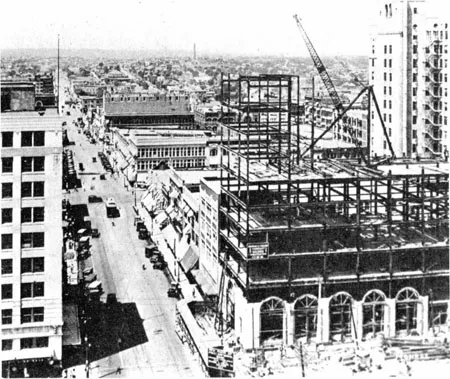

The “Magic City.” Fourth and Main, looking north, 1918.

Courtesy of McFarlin Library University of Tulsa

II

Native Americans were the first settlers of the area which was to become Tulsa. The next racial group to be among the area’s inhabitants were not whites, but blacks. Afro-Americans were present in the Tulsa area probably throughout most of the nineteenth century, as the Cherokees and the Creeks—who were moved onto what had been Osage lands beginning in the 1830s—had black slaves. After the Civil War and the coming of emancipation, black freedmen remained in the area and were not without a voice in the local government. Freedmen in the Coweta District of the Creek Nation, in which Tulsa was later located, were sometimes chosen for district public offices. Blacks were also involved in the Green Peach War, a “serious political disturbance” which broke out among the Creeks in 1883.10

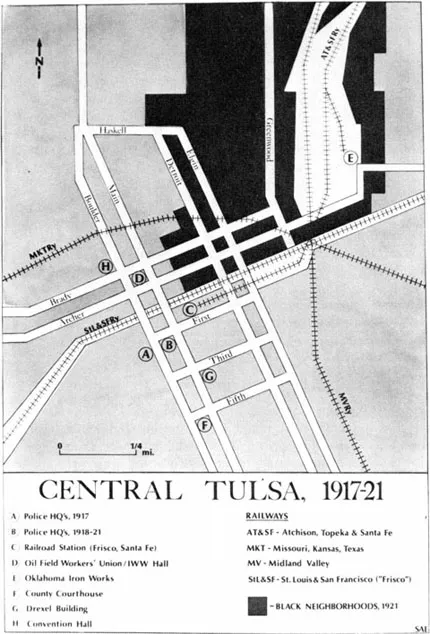

As the nineteenth century waned, and Tulsa grew, the city’s black community became larger and more established. Two black churches, the Vernon African Methodist Episcopal Church and the Macedonia Baptist Church, had their foundings in 1895 and 1897, respectively.11 Immigration no doubt also affected the social life of black Tulsa, as blacks born in other states became the majority within the black community. In 1900—when blacks comprised about 5 percent of the total population of the city—more black Tulsans had been born in Missouri than in Indian Territory, with Mississippians and Georgians ranking third and fourth. Most of the adults at that time worked as day laborers, servants, or housewives, but there also was a black lawyer, blacksmith, stonemason, and a full-time preacher. A fair number of the domestic workers “lived-in” with their white employers.12 As for the others, apparently it was not until 1905 that black Tulsans began to live along Greenwood Avenue in the northeast section of the city, when a strip of land in that area was sold to a group of blacks. One year later—one year before statehood—Tulsa boasted a black newspaper, the Tulsa Guide, edited by G. W. Hutchins. And when statehood came, black Tulsa had two doctors, one barber, and three grocers among its business people.13

By 1910 the black population had grown to 10 percent of the total population of the city, and there was then at least one black trade union, the Hod Carriers Local No. 199. One year later, Barney Cleaver became Tulsa’s first black police officer, and a few years after that the Dreamland Theatre and other black businesses graced Greenwood Avenue. The second lowest black illiteracy rate of any county in Oklahoma testified to the presence of a black school, and over three-fourths of black Tulsa’s school-age children were attending school. A new black newspaper, the Tulsa Weekly Planet, edited by Professor J. H. Hill, was then in existence.14

While black Tulsans were “welcomed” to work at common labor, domestic, and service jobs in any part of the city, they were “not welcome” to patronize white businesses south of the tracks and in other sections of the city. This was a major reason, according to local historian Henry Whitlow, for the growth of Tulsa’s black business community, located primarily along Greenwood Avenue.15 Thus, in the early years of the twentieth century, Tulsa became not one city, but two. Confined by law and by white racism, black Tulsa was a separate city, serving the needs of the black community. And as Tulsa boomed, black Tulsa did too.

By the year of the riot, 1921, the black population had grown to almost 11,000 and the community counted two black schools, Dunbar and Booker T. Washington, one black hospital, and two black newspapers, the Tulsa Star and the Oklahoma Sun. Black Tulsa at this time had some thirteen churches and three fraternal lodges— Masonic, Knights of Pythias, and I.O.O.F.—plus two black theaters and a black public library.16

A focal point of the community was the intersection of Greenwood and Archer. This geographical location—a single corner—has had something of a symbolic life of its own in Tulsa for most of the twentieth century, as it has been a key spot of delineation between the city’s black and white worlds. The corner has even been mentioned in song. Beginning about 1941, Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys, a white “western swing” group which drew their music heavily from black sources, sang:

Would I like to go to Tulsa?

You bet your boots I would,

Let me off at Archer,

I’ll walk down to Greenwood

Take me back to Tulsa...17

And in the 1970s, a nationally known black musical group from Tulsa, the Gap Band, drew its name from Greenwood, Archer, and Pine streets.

Greenwood Avenue looking north from Archer, ca.1918

Courtesy of W. D. Williams

The first two blocks of Greenwood Avenue north of Archer were known as “Deep Greenwood.” It comprised the heart of Tulsa’s black business community, and was known by some before the riot as the “Negro’s Wall Street,” while an organizer for the National Negro Business League visiting black Tulsa in 1913 called it “a regular Monte Carlo.” Two- and three-story brick buildings lined the avenue, housing a variety of commercial establishments, including a dry goods store, two theaters, groceries, confectionaries, restaurants, and billiard halls. A number of black Tulsa’s eleven rooming houses and four hotels were located here. “Deep Greenwood” was also a favorite place for the offices of Tulsa’s unusually large number of black law...