![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Heir to a Personal Dominion

MENTION the Northern Neck to a present-day Virginian and there will arise in his mind the image of a long, flat finger of land still predominantly rural, still carrying landmarks left behind by a plantation aristocracy, still retaining in names like Westmoreland, Northumberland, and Lancaster reminders of Englishmen who settled there and established tiny outposts of British enterprise and culture. Three centuries ago those outposts flourished and multiplied against a background of tobacco. The soil of this slender peninsula was rich, its air was good, and its flanking rivers were nearby highways to Mother England.

Free of the swamplands and miasmatic “vapors” of watersheds farther to the south, the Northern Neck was a good place to settle down and build a home, to rear a family and make a fortune. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Virginians looked upon it as a hospitable wilderness and hoped to achieve those things. Once there, they learned to live with and manipulate the cumbersome system by which the Neck slowly evolved from a proprietary dominion (by 1700 almost wholly controlled by the Fairfax family) into a pattern of plantations owned by aggressive, ambitious settlers. Absentee control by the Fairfaxes aided this transition. Entail, primogeniture, and artful techniques in speculation completed it and led to the accumulation of vast estates. “Headright” patents of land, which elsewhere divided huge tracts into small parcels, never caught hold on the Neck. Therefore the measure of a man became the number of square miles in his estate and the number of window panes in his mansion. The glass cost more than the land.

Most prosperous were the planters. And among those fortunate few, more successful than most, were the ancestors of George Mason. By the time he was born in 1725 the Mason name had become synonymous with wealth and leadership, talent and taste. Between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers that flanked the Northern Neck there had sprung up an elite group of families. Their patriarchs were the leaders at the balls and the barbecues, the arbiters of justice in the courts. They owned the ferries, and they sat in the General Assembly. They were the Carters, the Lees, the Washingtons, the Masons.

From the very beginning, these families imparted to the Northern Neck a tinge of aristocracy that obscured the New World roots of the region. With land the basis for their wealth, it was the English model of elegance that was constantly portrayed as their ideal. It was the one they knew best. Few residents of the Neck would have called themselves Americans. When they thought of it at all, they probably thought of themselves as English-Americans, or simply as Virginians.

Born to the membership of gentlemen in this pleasant countryside, George Mason knew where to find the deer in its forests, the fish in its ponds and streams. Like the young colts he raced over the meadows toward a neighboring plantation, he was eager, exploratory, active, more active than he would ever again be, once his body had stopped growing and the yet-unsuspected gout had taken hold. To other second- and third-generation gentry he made himself an amiable companion. There would be plenty of time for them to step forward as the leaders of their class. The pattern had already been fixed, and before them were notable examples of the pathway to affluence and power.

Of these examples none was more impressive than that left by Robert (“King”) Carter. When Carter died, in Mason’s seventh year, he had acquired more than 200,000 acres of the Neck and had sat on the Governor’s Council in Williamsburg. Men like Mason’s father, and Augustine Washington, were either more modest or less speculative. They reasoned that between five and ten thousand acres would serve their needs temporarily. Their sons would discover such holdings adequate enough to launch them on their quest for the good life.

And good life it was for those landholders at the top rung of the Northern Neck’s social ladder. Douglas Southall Freeman found eight distinct classes in pre-Revolutionary Virginia, running from the gentry to the slaves, with those two ranks both “supposed to be of immutable station.” Between them stood small farmers, merchants, seafaring men, frontiersmen, servants, and convicts. Shifts in station could sometimes blur the social distinction between these middle classes; but if the rich did not get richer and the poor much poorer, at least they rarely swapped places. By Mason’s time the main route to riches was by inheritance—the passing from father to son of immense estates. It was not yet the age of the self-made man, though symptoms of the acquisitive itch for land were still to be seen.

Out of land ownership, which fixed a man’s place in this world of George Mason’s, grew a kind of pastoral aristocracy. “Like one of the patriarchs, I have my flocks and my herds, my bond-men and bond-women, and every soart of trade amongst my own servants, so that I live in a kind of independence on every one but Providence.” So boasted one Virginian early in the eighteenth century. Rich loam and its “exquisite weed” was the keystone of William Byrd’s personal dominion, and of the larger one called the colony of Virginia.

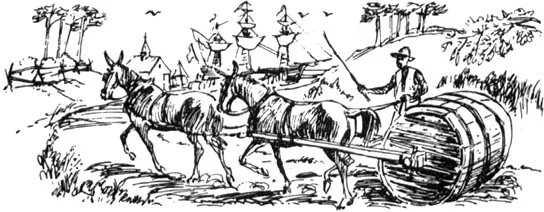

Tobacco, or notes representing tobacco, paid the bills abroad. Thousands of broad, brown leaves were pressed into the huge hogsheads that English merchants then jammed into their warehouses. Colorful damasks, silver plate, and choice Madeira came up the rivers during the good years. Smaller orders and overdue bills marked the lean ones. But year in and year out, tobacco supported the parson, paid the tax-gatherer, and entertained the royal governor. Seasoned travelers looked at the good life based on its cultivation and were reminded of the great English estates. The planters were “much the same as about London,” they said, “which they esteem their home.”

Yet tobacco, by 1725, was beginning to slip. Depressed prices, worn-out acres, and sharp practices by both planters and merchants rudely jolted the complacency of the Northern Neck. Inspection acts to insure standards of quality and weight helped to stabilize the trade though they could not postpone the end of the tobacco tyranny in Tidewater agriculture. Mason’s life spanned the decline and fall of the system, and only prudent management, developing with his responsibilities, set him apart from, many of his debt-enmeshed neighbors. Marked for early maturity through his father’s untimely death, Mason never forgot that it was better to be due a pound than to owe a shilling.

Some of this prudence came directly from his mother. A strong-willed woman with a widow’s concern for her growing children, she picked tutors to train her eldest son but did no small amount of drilling herself. As an aide in making decisions concerning the boy she enlisted John Mercer, Mason’s uncle and a highly respected lawyer. It was a happy alliance. Good libraries were rare in the colony, and at Marlborough, a few miles down river from Dogue’s Neck, Mercer owned one of the best. Book collector as well as lawyer, Mercer introduced the lad to shelves that held hundreds of the classics and almost every important legal treatise of the time, ranging from Coke’s commentaries on Littleton to Mercer’s own abridgment of the laws of Virginia. One volume that had cost his uncle five shillings must have made an impression, for it offered advice that Mason eagerly absorbed. Until he had his own copy, this edition of Every Man His Own Lawyer would do.

Days spent becalmed in the heady latitudes of Marlborough were not uninterrupted by outside diversion. To judge good horseflesh and “ride with a good saddle” were exterior signs of the gentleman, essential accomplishments. So was the curriculum of the race track, where the fortunes of some of his friends were either depleted or transferred. Mason could spot a good quarter horse and would occasionally back his judgment with a bet—a small one. There was risk enough in the fluctuating prices of tobacco and wheat; if he forgot that fact, his widowed mother reminded him.

Because he never enrolled as a student at the College of William and Mary he missed the chance to practice dancing as it was taught there. Yet he must have known the proper art, the way to take a lady’s hand, to execute a turn. Had not the good Governor Gooch declared that there was “not an ill dancer in my government”? Fencing was also taught, though it was a social adornment better suited to the European nobleman than to the Virginia gentleman. Instruction seldom graduated to the more complicated positions and parries.

A good horseman, a fair dancer, an indifferent fencer: they were skills rated in that order by men of good breeding. By his twenty-first birthday in 1746, Mason was, by all the standards laid down for him and his peers, well-bred. Well-proportioned, too, even handsome under the wig that hid his brown hair. Cleanshaven in the manner of the times, his face was pleasantly round-shaped, no hint of mystery there except for a shaded, rugged look around the lower jaws. His eyes: hazel brown, with strongly curving, bushy eyebrows that might better have fitted a face leaner and less full.

There was, in truth,little about Mason’s appearance at twenty-one to suggest his character. His scholarly bent was not reflected by a squint at the corners of his eyes; no lines yet appeared on his forehead to witness his defense against personal pain, his concern for the sorrowful state of affairs between England and her colonial subjects. Among friends, dressed in his London small-clothes, fashionable stockings sporting fancy clocks, neatly polished buttons and buckles, he was respected, if not yet distinguished. There would be time for that. Now he was simply rich.

Mason’s inheritance, on reaching his majority, included thousands of acres of choice farm land in Maryland and Virginia. To the west, still to be surveyed, lay more thousands of uncleared acres. The Northern Neck estate included a wide variety of utility houses and sheds, numerous slaves, livestock, tools, furnishings, and other personal property. Tobacco, in storage awaiting a higher price or deposited in London, was a respectable asset, even though debit balances for British goods probably offset it. There were also bills of exchange and scattered holdings of cash—all in all an ample beginning for a young planter.

Long aware that this day would come, Mason was prepared for the responsibility of management. He plunged into the business of running a plantation with an aggressiveness that eliminated any notion that hired stewards and clerks might handle the main business and leave him plenty of time for reading and leisure. At the end of a day in the fields, inspecting crops, riding fences, haggling with merchants over prices at the warehouses, Mason did find time for his leisure. Then he surrounded himself with books, his own and those from his uncle’s library, and proceeded to educate himself in a manner that was characteristically intense. Along with the wealth of legal writing available to him, he pored over medical treatises, bound volumes of English magazines, Shakespeare’s works, Rollin’s Ancient History, Stith’s History of Virginia, and reports of Parliamentary debates. Naturally perceptive, keen of intellect, Mason revealed an appetite for reading that was of the type satisfied only when sharpened; the turn of a page might bring forth an even fresher discovery than before. It was his distinctive intellectual curiosity that permitted him to keep pace with the best minds in Virginia during a period when men usually established themselves as leaders by the age of thirty.

ANN EILBECK MASON, “taller than the middle size, and elegantly shaped,” soon after her marriage to George Mason in 1750.

Possessed of wealth, wit, and intellect, Mason now lacked but two qualifications to meet the measure of a true son of the Northern Neck. He was a bachelor, and apparently a nimble one, considering the eligible young ladies who visited at neighboring plantations. “Eligibility” was important. The history of the Northern Neck had already become the history of interlocking family enterprise. Happily, no embarrassing shortage of candidates narrowed young George’s choice. Across the Potomac in Maryland his search ended on the plantation of Ann Eilbeck. The sixteen-year-old girl enraptured the bookish young planter, being (as he recalled) “elegantly shaped” with “her complexion remarkably fair and fresh.” On April 4, 1750, Ann and George stood before the Reverend John Moncure to repeat their marriage vows and begin a romantic partnership that would last for twenty-three years, and much longer in Mason’s heart.

Thus did the second half of the eighteenth century open propitiously for George Mason. With family ties now formed by the new bride at his side, he needed only one more item to make the world truly his oyster. That was a sturdy, elegant mansion for this remarkably fair lady and the children she would bear him. A proper home for a proper family would be the next order of business.

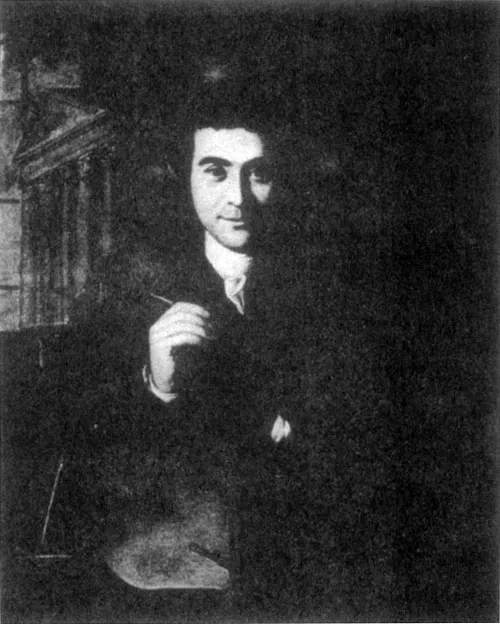

WILLIAM BUCKLAND, “carpenter & joiner,” left England to practice his craft in the New World. In addition to Gunston Hall, examples of his skill may still be seen in other Virginia and Maryland homes. Buckland died shortly after he sat for this portrait.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

A Proper Home

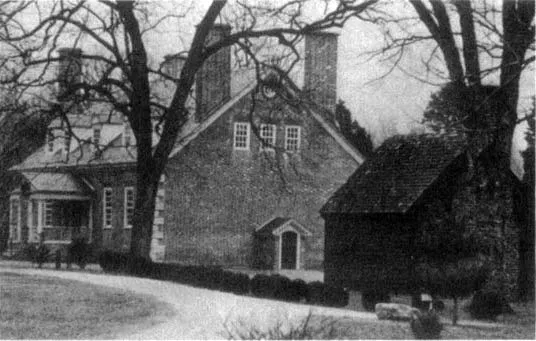

MASON could have built a larger house, but he planned Gunston Hall exactly as he was learning to approach most human endeavors—with moderation and thoroughness. The story-and-a-half brick, house grew toward completion between 1755 and 1758, taking on an aspect that was solid rather than grand. From the outside it looked small, deceptively so, for in fact it was quite roomy; with Mason’s ever-growing family, its planners needed to fill every nook and cranny with living space.

The supervising craftsman was an Englishman, barely turned twenty-one, who came to America indentured to Mason’s younger brother in 1755. Thomson Mason, preparing to leave England after studying law, had signed William Buckland at his brother’s bidding. Work on the foundations and walls was already in progress when this fledgling architect stepped ashore at Mason’s landing. The basic plan had been in the owner’s mind for many months, for it was an uncomplicated arrangement similar to a number of other homes in the area. But a man of Mason’s wide interests and responsibilities could not be on the scene all the time. Young Buckland seems early to have gained his confidence and convinced the master-of the estate that the right man had been picked for the job. No ordinary indentured servant, he had come to the colony as a skilled “carpenter and Joiner” who commanded twenty pounds salary per annum.

That the two men got along so well is a tribute to Buckland’s ability. His ideas—excellent ones, it turned out—had to be accommodated to those of his employer, for Mason was not the kind to give him a free hand. The Virginian was above all things a manager who liked to control his affairs down to the last detail. Mason insisted that the sand used in the mortar come either from wells or the “river shoar,” and exterior work called for mortar of stronger composition than that for inside partition walls. He warned a friend to be equally careful in watching such details. “I wou’d by no means put any clay or loam in any of the mortar,” he wrote, because it was not only a weak material but “it is very apt to nourish and harbour those pernicious little vermin the cockroaches … and this I assure you is no slight consideration; for I have seen some brick houses so infested with these devils that a man had better have lived in a barne than in one of them.”

No vermin would inhabit his palace. He wanted Gunston Hall to be the kind of dwelling his wife and family deserved, and the kind that proper hospitality, in a hospitable age, demanded. That goal was in his mind as he went over the plans with Buckland, checked the seasoning of the timbers, the riving of the shingles, the cut of the Aquia Creek stone quoins that were to square off the corners of the building. When new fires tested the chimney drafts in the spring of 58, the result of months of planning, four years of labor, and hundreds of pounds sterling stood ready for its final inspection.

MASON’S ORIGINAL PLAN for a traditional type of country home, with four rooms and a central hallway on the main floor, gave William Buckland ample room to practice his genius as a master woodcarver and joiner.

TRADITIONAL SOUTHERN HOUSES of the period had no end windows on the first floor. Mason’s plan provided three small upper windows for extra ventilation in the bedrooms and an outside entry to the basement that permitted precious cargoes of claret and madeira to be moved directly to the wine cellar.

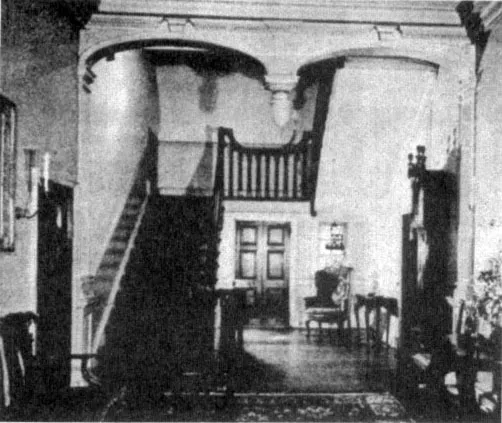

THE CENTRAL HALLWAY.

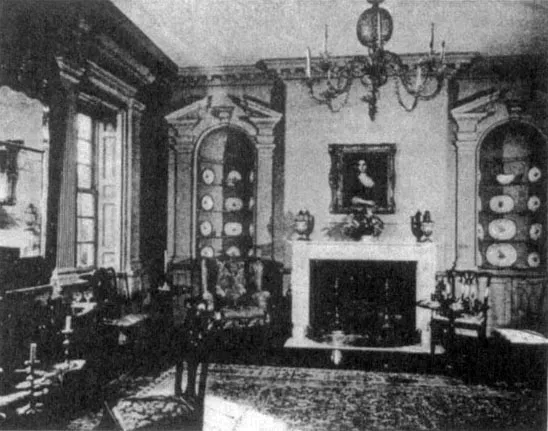

THE PALLADIAN DRAWING ROOM.

Buckland had served his master well. Mason was enchanted by Buckland’s skill as a woodcarver, and in that respect gave the Englishman free rein. Certainly the entire structure combined classic touches with original qualities of grace and form. Following the style of the day, the ceilings were high and the central passage wide, so that cool breezes could drift throu...