![]()

PART I

Discovering Queerness in Video Games

![]()

1

Between Paddles

Pong, Between Men, and Queer Intimacy in Video Games

First released in 1972, Pong (Atari) is widely celebrated as one of the first and most formative video games in the history of the medium. Published a little more than a decade later, in 1985, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s book Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire, is equally well-known within queer studies as a foundational work that helped shape the field. Apart from their revered places within their respective canons, Pong and Between Men may appear to have little—if anything—in common. Pong is a classic arcade game, later brought to a number of home game platforms, inspired by the sport of ping-pong. The original Pong is a rudimentary game; only the paddles, the ball, the net, and the score appear on-screen. It has no narrative, no characters, and certainly no explicitly LGBTQ content. By contrast, Between Men is all about characters, narrative, and what would likely today be called queerness. In her book, Sedgwick uses examples from British novels to articulate a system through which she sees male same-sex bonds forming via a triangulation of desire through women. Video games are not mentioned in Sedgwick’s book, and the abstracted forms represented in Pong make for an unexpected match with the detailed stories and dialogue analyzed in Between Men. Despite their many differences, however, these two classics can be seen to speak to one another in powerful ways. The dynamic structures that appear in both works in fact closely mirror one another: the erotic triangle described by Sedgwick and the geometric movement of the ball bounced back and forth between paddles in Pong. Both can be understood as interactive systems through which desire is communicated, connection is built, and queer intimacy takes form.

By juxtaposing Pong and Between Men, this chapter explores some of the new perspectives, parallels, and points of complication that arise when video games and queer studies are put in dialogue. This juxtaposition models one of the key scholarly methods for “discovering” the queerness in video games, the title of this first section of the book, especially when it comes to games that do not initially appear to relate to gender, sexuality, or LGBTQ issues. Directly pairing a highly influential work of queer theory with one of the best-known (yet rarely theorized) video games demonstrates how considering queerness and games together can cast new light on even those works that seem to be well-trodden territory. What is more, because both Pong and Between Men have been so foundational in their fields—both through their direct influence and through the later generations of work that they helped inspire—identifying the overlaps between them represents an important piece of the larger argument that queerness and video games are indeed profoundly linked. As this comparative reading shows, that link can be found already operating at the respective origins of video games and queer theory, long before LGBTQ characters made their first well-known appearances in mainstream games or game studies began engaging with theories of queerness. These connections reinvigorate and reverberate through both game studies and queer studies, pointing toward ongoing work that explores a wealth of alternative frameworks for making meaning from both queerness and video games.

Current queer game studies scholarship focuses primarily on bringing the interpretive lenses of queer theory to video games. Yet, as this re-reading of Pong and Between Men illustrates, the study of video games, play, and ludic systems can also enrich conceptualizations of queerness. Articulating the ways that Pong and Between Men speak to one another suggests a larger paradigm for thinking about issues of culture, identity, and resistance: through interactivity and rule sets. As Robyn Wiegman and Elizabeth A. Wilson have argued, the work of queer studies is not only to identify and celebrate antinormativity.1 It is also to use analytical tools informed by concerns of gender and sexuality to lay bare how norms (including norms of queerness) function. Thinking about queerness through video games has the potential to do just this. Games like Pong, driven by mechanics rather than story, shift the focus of queer theory away from narrative and toward interactions. Increasingly, game-like experiences, such as Vi Hart and Nicky Case’s Parable of the Polygons (2014), are modeling how video games can facilitate critical thinking about the systemic forces that shape society. Placed in conversation with Between Men, Pong offers a similar opportunity for critical analysis. It invites players to take part in the formation of queer intimacy through critique, creating space for alternative interpretations and emergent play. In this way, this juxtaposition productively complicates the dynamics originally described by Sedgwick in Between Men, while simultaneously demonstrating how Pong can be understood as a queer game.

Pong: Gameplay, History, and a Call to Critique the “Classics”

Pong is a classic video game in more ways than one. It exemplifies the types of games produced in the “golden era” of the arcade, it enjoys a revered place in the games canon and games history, and it has been, through generations of influence, formative for many waves of games that have followed it. In the intervening years since its original release in 1972, Pong has been updated and re-skinned (to use the terminology of the games industry) any number of times, but its basic gameplay remains the same. I will be describing and referring to the 1972 arcade version of Pong, since it is in this form that the game first achieved the widespread commercial success that launched its many later iterations.

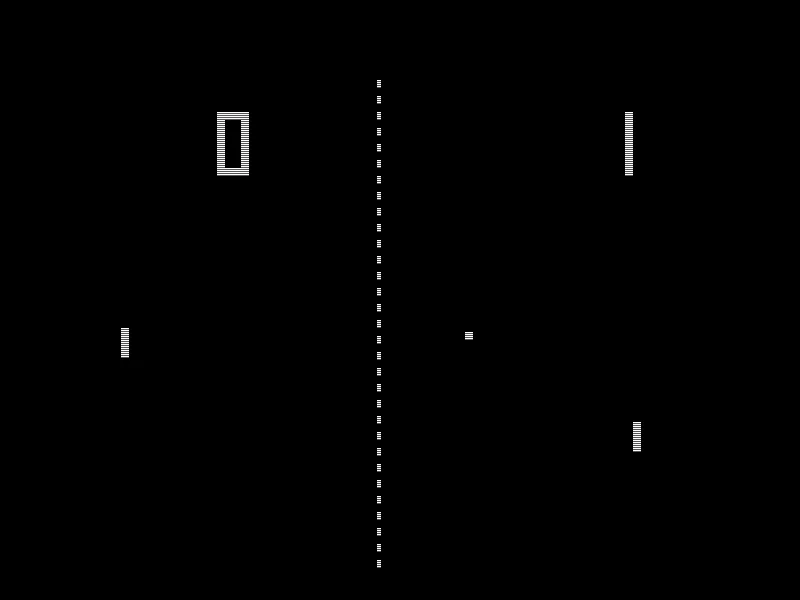

Though Pong’s gameplay may seem simple, each of its elements can be identified and interpreted. Designed as a translation of ping-pong to the then-nascent medium of the video game, Pong is a game for either one or two players (figure 1.1). Each opponent, whether human or computer (if the human player is playing alone, they play against the computer), is represented by a thin white rectangle, i.e., a paddle. At the center of the screen, dividing the play space from top to bottom, is a dotted white line: the net. Players’ scores are displayed prominently in thick, white numbers on their respective sides of the screen. As in ping-pong, the goal of Pong is to hit a ball, represented by a small white square, back and forth between players. If a player misses the ball, a point goes to their opponent. The ball itself is served onto the table at an angle by an unseen force. In order to hit the ball, players move their paddles along a vertical axis. Gameplay is controlled by only one point of input: a smooth metal knob that, when turned, slides a player’s paddle up or down. The aesthetics of the game, which is in black and white, are as minimalist as its controls. Pong’s 8-bit soundscape adds perhaps its most notable sensory element. When a player’s paddle hits the ball, the game gives off a bright, electronically inflected chirp; when a player misses, a harsher, longer penalty noise sounds. Together, these deconstructed elements make up Pong’s gameplay.

Figure 1.1. Pong (Atari, 1972). Creative Commons image via Wikimedia Commons.

The history of Pong, and of the game’s importance within the larger narrative of video-game history, has been told many times. Typically, Pong’s origins are recounted as a tale of genius breakthroughs by singular men—Atari employees Allan Alcorn and Nolan Bushnell, the game’s widely credited creators—whose innovative efforts and creative vision are said to have profoundly shaped video games as we know them today.2 While it is important to note the problematic gender and labor politics of this narrative, it is true that Pong was formative in the emergence of commercial video games in the 1970s, and that the technologies that were developed in part as a result of Pong’s success did lay the groundwork for how video games have been played for the last four decades. Not uncommonly, Pong is erroneously cited as the first arcade game, or even the very first video game. While other games preceded it on both counts (e.g., Spacewar! in 1962 and Computer Space in 1971), Pong did contribute significantly to the popularization of the arcade game and, soon after, the medium of the video game more broadly. Pong’s popularity helped kick off the production of the scores of games that soon populated arcades. The game also played an important role in the birth of the home game console. In 1974, hoping to build from their commercial success by creating new markets, Atari released Home Pong, an all-in-one console, controller, and game that allowed players to play Pong at home on their television sets. Expanding on this model, Atari released the Atari 2600 in 1977. From the Atari 2600 can be traced a lineage of consoles that leads up to the present day.3 In this way, Pong can be described as an ancestor of almost all contemporary video games.

In addition to its formative role in the commercial and technological evolution of video games, Pong has been highly influential from the standpoint of game design. It was the first video game to use a sports heuristic, and many of its basic elements—like its shared top-down view and centrally displayed score—have since become so standard in multiplayer games that it can be easy to forget that these too have design histories. Later games in which can be seen elements of Pong’s design influence, like Mario Tennis (Nintendo, 2000), have gone on to take their place as classics in their own right, spinning off long-standing and widely played series. Pong also holds a central place in the cultural imaginary as a synecdochic referent for video games themselves. Mentions of Pong frequently appear in other forms of media, such as film and television, as well as in popular writing on games, as in the title of Damon Brown’s 2008 book on the history of sexual content in video games, Porn and Pong. In these instances, the game is often deployed as a shorthand for retro games, the game arcade, or simply the medium of video games itself. In short, even as we might seek to resist retelling the glorified history of Pong as a celebration of individual genius, Pong’s notable place within the emergence and evolution of video games as a part of North American popular culture merits recognition.

For all that has been written about Pong, however, the game has rarely been considered through a theoretical lens. Perhaps because Pong seems so basic in its gameplay, its controls, and its forms of on-screen representation, it has been largely overlooked by those interested in closely interpreting video games. In this sense, Pong stands in contrast to other classic arcade games, like Pac-Man. The Ms. Pac-Man character has been a point of interest and debate for feminist game commentators and fans alike. Some of these have condemned Ms. Pac-Man as a shallow re-gendering of Pac-Man himself. Isn’t she just, as Anita Sarkeesian asks, “Pac-Man with a bow?”4 Others have sought to reclaim Ms. Pac-Man as gaming’s earliest and perhaps most beloved transgender character.5 Yet Pong too, though it seems to represent no characters on-screen, deserves careful critique with an eye toward issues of gender, sexuality, and identity. Contained within Pong’s gameplay are rich metaphors for the communication of desire, the formation of intimate relationality, and alternative expressions of agency. As the resonances between Pong and Between Men will suggest, these aspects of the game can be seen as fundamentally queer. In a sense, interpreting Pong through a queer lens represents a retelling of the game’s already often-told history—and, through Pong, an important element of the larger history of video games. In this new history, Pong becomes a queer game that has long passed as an icon of straight gaming culture. Obfuscated, overlooked, yet deeply resonant, Pong’s queerness can be found just beneath its surface, where it waits to come to light.

Between Men: Structures, Limitations, and the Foundations of Queer Theory

Like Pong, Sedgwick’s Between Men has been foundational for its field. Sedgwick focuses her text on what she sees as a common social structure: the erotic triangle. The erotic triangle, for Sedgwick, describes a system in which intimacy is formed between men by routing desire through women. Sedgwick calls this a “graphic schema” for understanding how male-male bonds are formed within a cultural context of homophobia and the oppressive instrumentalization of women.6 She articulates the functions of the triangle through a discussion of erotic rivalry. “In any erotic rivalry, the bond that links the two rivals is as intense and potent as the bond that links either of the rivals to the beloved,” she writes. “The bonds of ‘rivalry’ and ‘love,’ differently as they are experienced, are equally powerful and in many senses equivalent.”7 To illustrate the mechanisms of these bonds, Sedgwick uses examples from mid-eighteenth- to mid-nineteenth-century British novels. Through these works, Sedgwick describes a system of male-male bonds that fall on a spectrum between the homosocial and what she calls the homosexual, but which could be more appropriately called the homoerotic. (In her 1993 preface to the second edition of Between Men, Sedgwick admits that the book’s shortcoming is in its blanket claims about male homosexuality and its lack of engagement with perspectives from gay men.)8 The vectors through which these bonds form, according to Sedgwick, are as much related to power as to desire. “The homosociality of this world … is not that of brotherhood,” she asserts, “but of extreme, compulsory, and intensely volatile mastery and subordination.”9 In this sense, ...