![]()

1 | Jazz, “Great Black Music,” and the Struggle for Racial and Social Equality in Washington, DC Maurice Jackson |

After years of abolitionist activities, by black and white, President Abraham Lincoln on April 16, 1862, eight and one-half months before the Emancipation Proclamation, signed the DC Emancipation Act, freeing more than three thousand enslaved African Americans in the District of Columbia.1 Yet Washington remained a town with Southern sensibilities, customs, and traditions. Over the years a system of de facto and de jure segregation emerged in the city. For more than a hundred years after slavery ended, African Americans in the nation’s capital continued to seek equality under the law. While they fought for justice through the legal system and in Congress, they gave full expression to their pride and determination through music in all its forms, from folk, gospel, and spirituals to the blues, classical, and jazz. The result is today called Great Black Music, and it continues in constantly reinvented forms.2 Washington, as one of the most vibrant centers of African American culture in the country, has been both enriched by the music created and performed here and changed, however slowly, by its presence. During the long struggle for desegregation, jazz in particular provided a common ground for blacks and whites to find a space and a place to mingle and celebrate great music together.

Progenitors: From Will Marion Cook to James Reese Europe

Washington was home to two of the founders of Great Black Music, Will Marion Cook and James Reese Europe. A concert violinist, Cook received excellent classical training in both this country and Europe but as an adult found inspiration in traditional African American folk tunes and spirituals, incorporating them in his compositions. Bandleader and composer Europe was outspoken in his belief that “we colored people have our own music that is part of us. It’s the product of our souls; it’s been created by the sufferings and miseries of our race.”3 Both men lived in Washington when they were young, and their outlooks on life were inevitably shaped by DC’s social landscape.

Between 1890 and 1918, the African American population in Washington grew dramatically. Blacks moved to the city in large numbers to flee the lynch mobs, political and economic oppression, and poverty of the South. The prospect of steady employment in the federal government provided unique opportunities for African Americans and accounted in part for this migration. These federal jobs also contributed to the emergence of a black middle class, who generally lived near Howard University. Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote in 1901: “Here comes together the flower of colored citizenship from all over the country. . . . The breeziness of the West here meets the refinement of the East, the warmth and grace of the South, the culture and fine reserve of the North.”4

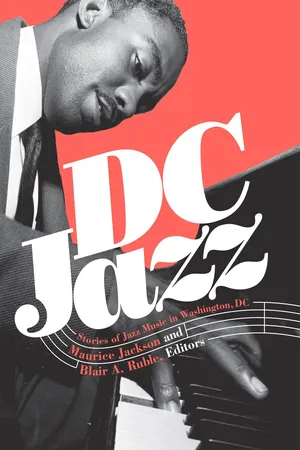

Photo 1.1 Leadbelly and Martha

Folklorist Alan Lomax photographed newlyweds Huddie “Leadbelly” Ledbetter and his wife, Martha, in 1935, while Lomax was recording Leadbelly for the Library of Congress. Leadbelly’s country blues were part of an African American idiom that black musicians had turned to for inspiration, drawing from traditional songs and melodies to create their own music. The resulting works together have been called Great Black Music, of which jazz is a vital part.

The election of Woodrow Wilson marked a turning point for this population. In 1912, before Wilson’s inauguration, the founder of Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington, believed that “the eyes of the entire country are upon the 100,000 Negroes in the District of Columbia.”5 But the next year, after Wilson became president, Washington was less optimistic about the prospect of black advancement, telling a colleague: “I have recently spent several days in Washington and I have never seen the colored people so discouraged and bitter as they are at the present time.”6 Wilson had begun to implement policies that segregated black employees within the federal government. Between 1910 and 1918 the proportion of black employees within the federal service declined from nearly 6 percent to 4.9 percent.7

During these years, racial lines hardened in other ways. Despite the presence of a black middle class, the overwhelming majority of Washington’s black population was poor. Most lived in crowded neighborhoods and slum-like alley dwellings because of racially restrictive housing and economic segregation. The Alley Dwelling Act of 1918 (and, later, 1934) condemned the small hovels, primarily inhabited by blacks, and ultimately forced entire neighborhoods to relocate to the southeast quadrant of the District, across the Anacostia River. Labor unions resisted black membership, so there were few ways to escape poverty. Most blacks continued to work as domestic and low-skilled laborers with little hope of advancement.8

Within this milieu, Washington native Will Marion Cook emerged as one of the founders of Great Black Music. Born in 1869, Cook was the son of John Harwell Cook, the dean of the Howard University Law School. At age fifteen he began violin studies and composition at the Oberlin Conservatory.9 Then, with the support of Frederick Douglass and members of the First Congressional Church, where Douglass had organized a recital, money was raised for Cook to attend the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin, Germany, from 1887 to 1889.10 In September 1890, the Indianapolis Freeman, an early African American newspaper, noted “the formation of a new Washington, D.C. orchestra with Frederick Douglass as President and Willie Cook as director.”11 But, according to Europe biographer Reid Badger, it “failed to last a year—despite the backing of Frederick Douglass and the leaders of Washington’s black society—in part because it followed too closely the European ‘high culture’ model.”12

Cook then attended the National Conservatory in New York, where he studied in 1894 and 1895 with the Czech-born composer and conductor Antonín Dvořák. Dvořák had been recruited to the conservatory in 1892, and in 1893, not many months after his arrival, composed the symphony From the New World (No. 9 in E minor), which incorporates American folk tunes. Dvořák’s association at the conservatory with African American composer Harry Burleigh inspired him to write “Goin’ Home.”13 In an interview in the New York Herald Tribune on May 21, 1893, he said, “I am now satisfied that the future of this music must be founded upon what are called Negro melodies. This must be the real foundation of any serious and original school of composition to be developed in the United States. . . . These are the folk songs of America, and your composers must turn to them. All of the great musicians have borrowed from the songs of the common people.” Dvořák also said, “In the Negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.”14 A few days later the Tribune editorialized that “Dr. Dvořák’s explicit announcement that his newly completed symphony reflects the Negro melodies, upon which . . . the coming American school must be based . . . will be a surprise to the world.”15 The same week the Paris Herald carried articles on and interviews with Dvořák, May 26–28, and ran the commentary of Joseph Joachim, “a distinguished violinist and pedagogue who may have already been exposed to American Negro music through his student, Will Marion Cook.”16

A few years later W. E. B. Du Bois, in his classic essay “The Sorrow Song” in The Souls of Black Folk, wrote, “The Negro folk song—the rhythm cry of slavery—stands today not simply as the sole American music, but as the most beautiful expression of human experience born this side of the seas. It has been neglected, it has been persistently mistaken and misunderstood; but notwithstanding, it still remains as the singular spiritual heritage of the nation and the greatest gifts of the Negro people.”17

In 1898 Will Marion Cook, in collaboration with poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, composed the musical Clorindy; or, The Origin of the Cakewalk. Cook wrote that he borrowed ten dollars and went to Washington to find Dunbar. They “got together in the basement of my brother John’s rented house on Sixth Street, just below Howard University, one night and about eight o’clock . . . where without a piano or anything but the kitchen table, we finished all the songs and all the libretto and all but a few bars of the ensemble by four o’clock the next morning.”18 Drawing on African American language and melody, the one-act musical opened that year in July, the first all-black cast to appear on Broadway. After the success of Clorindy, according to musicologist Eileen Southern, Cook “became a conductor of syncopated orchestras and a composer of art music . . . [and] ‘composer in chief’ for a steady stream of musicals, most of which featured the celebrated vaudeville team of George Walker and Bert Williams.”19 Like Dvořák, Cook also began to incorporate folk music into his compositions and in 1912 published A Collection of Negro Songs.

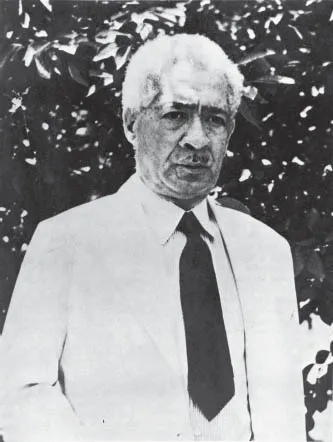

Photo 1.2 Will Marion Cook

Native Washingtonian Will Marion Cook was trained as a concert violinist, studying abroad and at the National Conservatory in New York, but came to believe that African Amer...