![]()

Part I

THE HISTORIC MOMENT

![]()

1

NEW HISTORIANS AND

THE DECLARATION

When we look at the fast-growing field of human rights literature, it might be helpful to separate at least four (or perhaps five) possible fields of discussion, each with a different aim or emphasis and also quite different sources. Since the phenomenon of human rights is presently occurring but also has quite a history, all the authors writing on human rights are in some way bound to be historians, going way back to ancient times or narrowly focusing on our contemporary era. Even so, I find it helpful to approach the literature of human rights with this simple diagram or flowchart in mind: idea → UDHR text → system → movement.

The reader should take these arrows very loosely as both chronological and causal indicators. I think of the historical idea of human rights as preceding and causally (note the “loosely” above) leading to the text of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. And I think of the UDHR text as being the inspiration for and in that way the cause of the legal human rights system that has enveloped our world and similarly as being the foundational text for the huge human rights movement we find operating today on all continents and in all countries.

I am not suggesting that all human rights authors and activists subscribe to this flow of events. But this diagram does underlie the arguments of this book. In various chapters I seek to explain or establish one or more of these arrows. My view is that when authors, as some do, shift back and forth between the various segments or discourses of this chart, they make it difficult for readers to evaluate the theses of their books or articles. I present a detailed case of this in chapter 2. Much of the present chapter is devoted to my use of this diagram as bins into which I suggest we drop various recent human rights publications. This exercise puts my views at odds with much of the recent literature on human rights in the sense that many human rights authors do not limit themselves to writing in just one category or bin of the chart. Many shift too quickly from bin to bin, paying insufficient attention to the causal arrows or—as we sometimes do in our sums—forgetting to carry anything over from one bin to the next.

The thesis of this first chapter is that the link between the event of the Holocaust and the UDHR text is frequently downplayed or ignored and, in my view, endangered. I argue that what I call the “new historians” (because they have spoken up recently) have downgraded the UDHR text far below the status it should have in our modern conception of human rights. The reason for this neglect is the lack of interest in the influence of the Holocaust on the writing of the UDHR. In the other three chapters of this book, I further explore the connection between the event of the Holocaust and the declaration. In what follows I put some authors and their articles or books into the chronological bins of this chart.

The Idea before the 1940s

In human rights literature, one can find a body of work that discusses primarily the history of the idea (or concept) of human rights. Some of these intellectual historians trace the idea of human rights way back to ancient times (Lauren 1998; Ishay 2004; Wolterstorff 2008), while others, like Moyn (2010) and Eckel (2014), believe it originated in the 1970s. Of the authors mentioned, Lauren’s account of the “evolution” of the concept in the 1940s is the most complete. Yet, because he does not link the Holocaust explicitly and directly to the declaration’s text, his otherwise excellent history weakens the unique role the Holocaust had in the birth of our modern conception of human rights. None of the writers who take the idea all the way back to the Greeks, Romans, or Christians and then connect that lineage to our own times do justice to the event of the Holocaust, which this book argues is the birthing ground for the contemporary notion of human rights. This is not to say that ancient philosophers like the Stoics had no thoughts about a universal ethic. It is only to say that the idea of human rights does not really have a smooth or incremental evolutionary history that finally blossomed after World War II or even later than that. Against this idea of a final blossoming, I maintain that the contemporary notion of human rights burst on our world on account of the Nazi horrors, which is a thesis I defend in detail in chapter 3, preparing the ground in chapters 1 and 2.

Some authors believe the idea has a long history but choose to lift up only one particular historical era for attention. While in Bury the Chains Adam Hochschild (2005) wrote about the British antislavery movement, Elizabeth Borgwardt (2005) expanded Franklin Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms into A New Deal for the World. Lynn Hunt in her Inventing Human Rights (2007) has a similar era-focused approach when she argues that human rights were invented around the time of the French Revolution. This literature on the history of the idea of human rights is probably the largest of the four discourses I mentioned, for these historical explorations readily overlap with the other bins in the chart. Someone can write a history of water and either have or not have any additional interest in the chemical composition of water. In that way historians of the idea of human rights differ quite a bit in their explorations of the content of the idea of human rights, definitionally speaking. At that point the emphasis shifts from the history of the idea to the philosophy of the concept of human rights, and the author becomes a philosopher more than a historian. Both Nicholas Wolterstorff (2008), who traces the idea back to Judeo-Christian beginnings, and Lynn Hunt (2007), who sticks to the invention of the idea during the Enlightenment era, have a philosophical interest in the content of the idea of human rights. These authors do not just help us see the historical trajectory of the idea; they also share their views on what the content of the concept of a human right is. Their historical work therefore runs over into what in the second half of this volume I call the “Philosophic Moment” of human rights though I do not give either of them a role to play there.

One book of essays, Revisiting the Origins of Human Rights (Slotte and Halme-Tuomisaari 2015), has not just revisited the origins of our idea of human rights, but its editors in their introductory essay specifically focus on the timeline arrow between the first bin idea and the second one of the UDHR text. They point out that the open-endedness of the idea in its history fits poorly with what they call today’s “textbook narrative,” according to which human rights are “entities with an absolute, predefined essence.” I do not question the editors’ claim that their contributors give us an idea of human rights that is quite “open-ended and ambiguous . . . [and] . . . formed around an ideal of the universal human being as free and equal in particular” (1). But I do question that this idea “corrects” what they say is “the textbook narrative,” in which human rights have an “essence” that sets the tone for us today. I agree that there was indeed a tightening of the idea of human rights in the 1940s, but not along the lines of a “predefined essence.” The puzzle then is why there was this “tightening” (to call it that)—on which the editors and I agree—instead of how the history of the idea (as seen in these essays) corrects the contemporary “textbook narrative.” I see no correction between what the contributing essays reveal is an open-ended idea and our own contemporary notion of human rights. Rather, I see a new start because of the intervention of the Holocaust into the history of the idea.

The editors wrap what I see as the main impulse behind our contemporary notion of human rights into a vague textbook narrative that I think happens to be correct but that is anchored in the outside Holocaust event instead of having evolved internally. If the content of the “textbook narrative” is properly specified, as it is in this book, then no correction was needed, because the tightening that took place and resulted in our contemporary notion of human rights is best explained by the event of the Holocaust, out of which cauldron came the text of the Universal Declaration. This Holocaust birth of that text constitutes the contemporary narrative of human rights, or so I argue.

I agree with the editors that there is an “internal coherence, logical continuity and comprehensiveness” to the contemporary notion of human rights, but I differ on what the source of these characteristics is. The editors do not tell us what produced these characteristics other than referring readers to some prominent law textbooks, like Henry J. Steiner and Philip Alston’s very complete and often updated International Human Rights in Context: Law, Politics, Morals, which I myself used for some ten years in different editions (Slotte and Halme-Tuomisaari 2015, 3n3). Checking law textbooks, the editors got the “sneaking suspicion” that they “were effectively reading the same textbook narrative over and over again, as if it had been simply copied and pasted from one book to the next” (4). Might there not be a standard law textbook narrative about the origin of human rights because, as I argue in chapter 4, the Holocaust had a huge impact on the writing of the declaration and in that way informed our own contemporary notion of human rights?

What irks the editors of this revisitation volume is that a batch of scholars have wrapped the “textbook narrative as legitimating myth” (Slotte and Halme-Tuomisaari 2015, 10–16), a myth that is totally insensitive to the realities found on the ground by the contributors to their volume. Here the editors claim that the openness of the idea before the 1940s conflicts with the tightening of the concept after that date. These textbook and mythmaking theorists ignore “discussions of how reality is always mediated through language, thus resonating with ‘hermeneutic naiveté,’ the belief in ‘immaculate perception’” (citing Gardner 2010, 10). The editors “paired” this mythical status of the contemporary notion with their own earlier suspicions and conclude that “the textbook narrative is a story with unknown origins and authorship that is frequently presented without references, yet with virtually unaltered details”; at this point the story has started “to resemble a myth” (11). I think the editors are tempted by this mythical origin of our contemporary notion of human rights because they themselves have no better explanation for “the internal coherence, logical continuity, and seeming comprehensiveness” of that notion. I ask whether instead of being hermeneutically naive these textbook authors may not have experienced the reality of the Holocaust through the mediation of human rights language.

The entire revisitation volume, editors and contributors alike, ignores the main reason why our own notion of human rights is tighter than the idea before 1948. This is especially evident in part 3 of the volume (titled “Institutional Practices and Relations of Rights: Towards the Universal Declaration of Human Rights”) because none of the essays even in this part focus specifically on the drafting years (1946–48) of the UDHR. Yet these are the years our notion of human rights was made internally coherent and comprehensive beyond anything that came before. The results can be seen in the UDHR preamble and its thirty articles, unanimously adopted by the 1948 Third General Assembly of the United Nations.

If we separate the idea (in its historical sense) from the concept (in its philosophical sense), then in the first three chapters of this book I defend the late 1940s (specifically 1946–48) as the historic moment for human rights, and in the last two chapters I defend those same late 1940s years, running over into the 1950s and 1960s, as the philosophic moment for human rights. These two moments for human rights overlap because each is defined by the causal connection I defend between the Holocaust and the text of the Universal Declaration. Before I discuss the second bin of our chart (idea → UDHR text → system → movement), I need to explain that the Universal Declaration and its legacy make up just one of two tracks that came out of the cauldron that was the Holocaust.

The Holocaust Cauldron

That the Holocaust was a cauldron out of which came numerous horrors, some leading to numerous prosecutions—and not just the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials—has recently been made clear by Dan Plesch in his revealing book Human Rights after Hitler (2017). Plesch records in detail the work done by the United Nations War Crimes Commission (UNWCC) in the years 1943–48. By the time the commission folded owing to lack of support by the United Kingdom and the US State Department, it had aided in the indictments of “more than thirty-six thousand individuals and units” (5). “The records,” says Plesch, “overturn one of the most important accepted truths concerning the Holocaust: that despite the heroic efforts of escapees from Nazi-occupied Europe, the Allies never officially accepted the reality of the Holocaust and therefore never condemned it until the camps were liberated after the war” (6). In an early chapter, Plesch shows how “contrary to conventional understanding, the Allies did in fact repeatedly and in detail condemn what we now call the Holocaust, as well as other crimes committed by the Nazis” (4). In his fifth chapter, Plesch describes indictments “for anti-Jewish persecution” that “appear to have been unknown to scholars for the last seventy years” (112). The soldiers indicted were mostly members of the Wehrmacht (armed forces), the Schutzstaffel (SS), the Sicherheitsdienst (the Security and Intelligence Service), and the Geheime Staatspolizei, or Gestapo. The indictments were “against low- and mid-level participants in the extermination of the Jews because their actions were such an important part of Nazi crimes and because the general assumption is that there was very little attempt by the victorious Allies to take legal action against those who exterminated the Jews” (113). Plesch’s table 5.1 gives us a list of indictments for anti-Jewish crimes submitted to the UNWCC. It lists 3,999 for Belgium, 55 for Czechoslovakia (52 versus Germany and 3 versus Hungary), 14 for Denmark, 93 for France (91 versus Germany and 2 versus Italy), 16 for Greece (4 versus Bulgaria and 12 versus Germany), 4 for Luxembourg, 110 for the Netherlands, 9 for Norway, 372 for Poland, 24 for the United Kingdom (21 versus Germany and 1 each for Italy and Japan), 5 for the United States (4 versus Germany and 1 versus Japan), and 42 for Yugoslavia (30 versus Germany, 7 versus Hungary, and 2 versus Italy). These anti-Jewish indictments are part of a far larger and more general horror show.

The UN War Crimes Commission operated as an international clearinghouse for the prosecution of mostly German, Italian, and Japanese war criminals. The seventeen member nations of the UNWCC presented to the commission dossiers and charge files that summarized the cases they wanted to bring. Between 1944 and 1948, the UNWCC approved more than 36,000 individuals and units for prosecution. “If the cases were approved, the individuals and units were listed as accused and the nations concerned sought to apprehend them and bring them to trial in national courts” (46). One of Plesch’s tables shows the nationality and the numbers of persons charged by the governments that were UNWCC member nations and therefore listed by the commission: Albanian, 38; Bulgarian, 422; German, 34,270; Hungarian, 69; Italian, 1,204; Japanese, 363; Romanian, 4. Different tables break down the numbers of prosecuted people into Germans, Italians, and Japanese by countries that filed the charges and conducted the prosecution. Following is a list of nations that prosecuted German persons with the number in parentheses; some of the trials, including most US ones, were held in the respective German occupation zones: Belgium (4,592), Canada (30, plus through the UK), China (1), Czechoslovakia (1,543), Denmark (159), France (12,546), Greece (339), India (through the UK), Luxembourg (90), Netherlands (2,423), New Zealand (through the UK), Norway (209), Poland (7,805), the United Kingdom (1,709), the United States (828), Yugoslavia (1,926), UNWCC (70) (table 4.2). Additionally, as seen from these numbers, Ethiopia (10), France (85), Greece (191), the United Kingdom (188), the United States (3), and Yugoslavia (809) charged many Italian persons (table 4.3), and Australia (94), France (3), the United Kingdom (120), and the United States (223) charged Japanese persons (table 4.4). All this activity took place before the fall of 1948, when the UNWCC stopped operating because of a lack of funds (mostly withheld by the US), and much of it commenced long before the end of the war (see Plesch 2017, chap. 5). In his essay “The Two Different Ways of Looking at Nazi Murder,” Christopher Browning reports Christian Gerlach’s calculation “that altogether in World War II between six and eight million non-Jewish noncombatants died alongside six million Jews at the hands of Germans and their allies and supporters” (Browning 2016, 58). That adds up to between 12 and 14 million Nazi-caused deaths.

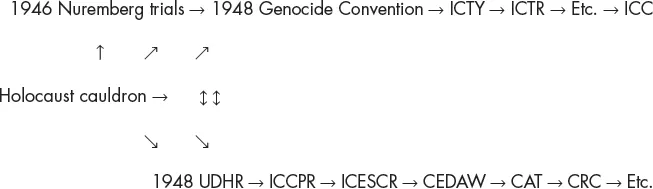

I ask my readers to imagine all these murders and all this collecting of evidence, filing of charges, and conducting of trials in many different countries and place their impressions into the cauldron of figure 1.1, which shows my new bifurcated chart, the top layer of which traces the legacy of the Nuremberg trials. Then I ask that they mix into this same cauldron the inevitable raising of social and Holocaust consciousness in the nations where these murders and trials took place, and they will gain an understanding of the birth of the chart’s lower track, on which I placed the most important noncriminal human rights texts. As Plesch makes clear, the phrase “human rights” can refer to a system that monitors violations of international criminal law, but it can equally well refer to the moral and legal norms that govern the noncriminal civil, social, economic, and cultural spheres of nations. Violations of human rights can therefore be seen as violations of international criminal codes, as abundantly shown by Plesch’s newly revealed data and portrayed on the upper level of our chart. And they can also be seen as violations of noncriminal international moral and legal norms codified in the texts I list on the lower level of the chart. Plesch points out that the combined efforts “from political parties and religious organizations, from governments exiled to London from Europe, from China and the pre-independence government of India, and from a few Anglo-American officials contributed to the creation of the International Military Tribunal (IMT) that tried the Nazi leadership at Nuremberg, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention” (48). For obvious reasons I have designated the last two items—the Universal Declaration and the Genocide Convention—coming out of this whirlwind of diplomatic and juridical activity as the lead texts of the bottom and upper track, respectively.

FIGURE 1.1: Two-track flowchart. ICTY = International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia; ICTR = International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda; ICC = International Criminal Court; UDHR = Universal Declaration of Human Rights; ICCPR = International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; ICESCR = International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; CEDAW = Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; CAT = Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman, or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; CRC = Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Since the two systems have a common origin in World War II (before which the sovereign immunity model held sway), it makes sense to think of this system as a bifurcated one that split at the time of its birth into two parts, sort of like twins. I put in so many arrows to indicate that both in reality and in the realm of ideas, the Holocaust was indeed a cauldron spewing out events and texts that eventu...