![]()

Part One

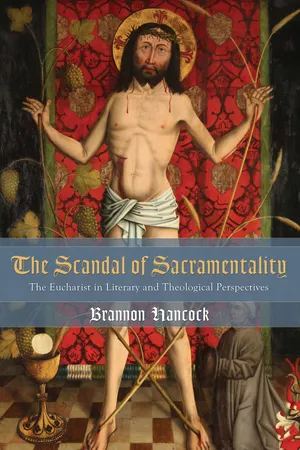

The Scandal of Sacramentality

![]()

1

Skandalon

Stumbling over Sacrament

One stumbles, then, on the sacrament, as one stumbles on the body, as one stumbles on the institution, as one stumbles on the letter of the Scriptures—if at least one respects it in its historical and empirical materiality. One stumbles against these because one harbors a nostalgia for an ideal and immediate presence to oneself, to others, and to God. Now, in forcing us back to our corporality, the sacraments shatter such dreams.

What is a Sacrament?

Before we are able to discuss sacrament as a linguistic or a corporeal scandal, we must have a basic understanding of what a sacrament is. In this chapter, we will establish what we mean by sacrament and sacramentality, and examine the reasons this concept has been a stumbling-block to Christian theology and liturgy. Any understanding of sacrament must be tethered closely to the entire Christ event, to the biblical witness concerning the person of Jesus Christ and the sacred meal he instituted in the Last Supper. However, sacraments must also be understood as cultural artifacts of a sort; indeed the Christian concept of sacrament derives directly from an existing concept found with the surrounding Roman cultural context. We must take this into account as well. Finally, sacrament must be understood in relation to signs and symbols. The writings of St. Augustine and Paul Tillich will assist us in understanding the characteristics of sacrament as a unique species of religious symbol.

Once this is established, we will turn our attention to the relationship of the sacraments, and the Eucharist in particular, to the Church. Any Christian concept of sacrament is meaningless apart from the person and work of Christ, and indeed from its inception the Eucharist has been regarded as the Body and Blood of Christ. But the Church is also understood to be the Body of Christ, a designation that derives directly from the eucharistic action of the Church. Therefore, we must determine how the Church is constituted as Church by the Eucharist—how the Eucharist makes the Church. Yet inherent to the scandal of sacramentality is the tendency to both stabilize and de-stabilize, or as David Power has observed of all rites, to both gather and scatter. That which provides the Church with her very being and identity, her sacramental function and form, is also that which strips the Church of every possession, power, and authority, calling her to be broken and poured out, like the eucharistic elements and the body and blood of Christ they represent. In this way, the Eucharist simultaneously makes and breaks the Church.

The word sacrament comes from the Latin word sacramentum, which, along with mysterium, was used to transcribe the Greek term mystērion or “mystery” in Latin translations of the New Testament. Henri de Lubac points out that in the “language of the liturgy, as with that of exegesis, mystery and sacrament are often used interchangeably. The Latin version of the New Testament translate mystērion equally by either word.” As de Lubac has demonstrated in detail, the phrase “mystical body” (corpus mysticum) of Christ was first applied to the Eucharist—that is, Christ’s sacramental body which mediates his historical body—but the phrase was gradually detached from the Eucharist and transposed into an exclusive link with Christ’s ecclesial body, the Church. This shift represents a significant step in an incremental departure from the mysterious and mystical nature of sacraments in Western Christianity in particular, and by extension in Western thought in general. By making this point, we wish to highlight the fundamental mystery of the Christian sacraments, which were and still are referred to as mysteries in Eastern Christianity. This mystical and mysterious quality must not be forgotten or neglected, for it is an even more originary concept to the meaning ascribed to the ancient Christian rituals commonly called sacraments.

Sacramentum was borrowed from the surrounding Roman cultural context, where it might refer to a ritual oath sworn by a Roman soldier in allegiance to the emperor, or more generically to something set aside for sacred or religious uses. The term is not adopted in Christian theology to describe various rites of Christian worship until its usage by Tertullian near the end of the second century. One of the struggles of the early church was against persecution by a surrounding culture which did not recognize Christianity as an acceptable religion. In fact, after Justin Martyr, Tertullian is one of the earliest apologists for the societal legitimacy of Christianity. With this struggle emerges the inevitable but somewhat problematic tendency to define Christian faith and practice according to extant religious traditions already deemed acceptable by the surrounding culture. And so, in their effort to defend themselves as good citizens and harmless practitioners of their faith, the apologists borrowed concepts like “mystery” or “sacrament” from the surrounding culture to explain their own practices. In the long-term, this tactic would shape Christianity’s understanding of its own rites in significant and lasting ways.

However, this is not a point to be passed over too quickly, for it proves central to the argument we offer here. We contend that to formulate any meaningful understanding of sacrament in a postmodern milieu, one must look to corresponding traces from the surrounding culture, for in such a way, the Christian notion of sacrament came into being in the first place. The sacred meal in which the early Christians partook of the bread and the cup as a “sharing” (1 Cor 10:16) in the body and blood of Christ pre-dates any application of the concepts mystērion or sacramentum to this ritual. As Christian faith and practice expanded and became more codified over time, these concepts from the broader (pagan or “secular”) culture were usefully appropriated to explain the significance of what appeared to the uninitiated to be at best secretive and at worst criminal religious rituals. Over time, these initially foreign concepts became indispensable to the Christian understanding of their own sacred rites. This observation is by no means a deconstruction of the primacy or integrity of the Eucharist or the theology of the sacraments—for indeed, the ritual predates the terminology and theology later applied to it—but rather demonstrates that to approach the notion of sacrament in the first instance, one is already firmly within the realm of hermeneutics, for to refer to the Lord’s Supper as a sacrament is to have already performed an act of interpretation or translation, the “carrying across” of meaning from one concept to another.

We have discussed the origins of the term sacrament and how it came to be applied to the Christian ritual partaking of the Lord’s Supper. We must extend this understanding by tracing the Lord’s Supper, through Scripture and the earliest Christian practice, to the institution of the Eucharist at the Last Supper and ultimately to the entire Christ event encompassing the incarnation, life, death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus Christ. But before we proceed to these theological connections, we must continue to pursue the question what is a sacrament? by considering the concept of sacrament in relation to the broader categories of sign and symbol.

Sign, Symbol, and Sacrament

Looking back across Christian history, sacraments have been described...