![]()

1

The Root from Which They Spring

Introductions

Take off your old coat and roll up your sleeves,

Life is a hard road to travel, I believe.90

I have been a university teacher for about a third of a century. My area of presumed expertise is theology. Theology is, if it is anything at all, a way of giving attention to God. Simply put, professors of theology profess God. That is why good people send their children off to college to study with theologians, with people like me. And I—professor that I am—do profess God, overtly, loudly, passionately. What is so embarrassing, though, is that I have such a hard time saying what it is that God means. You would think that someone laboring in this field for so long would have at least that much nailed down! Yet I must confess that I do not.

The problem is not that I am a closet infidel, hiding behind some plastic mask of public piety (like a candidate running for office). I try very hard to be honest and open, particularly where I am most professional. That is, my comprehension-failure is no secret. In fact I would think nothing would be more evident, as I go on and on in class, than that I strain just to get that black hole of a little three-letter word out. But, of course, my task as a professor of theology is not just to get that one word out; I am to throw out a whole galaxy of words and ideas and images and passions and practices that are agitated by and drawn into that black hole.

Of course, speaking of God in this way is hopeless. To say “God” in the field where I labor is surely not to say “a compressed and compressing density, that heaviest, darkest phenomenon of orthodox physics.” And though there are speculative physicists and writers of science fiction who think of a black hole as a portal to another, distant point in space-time—and it might not be out of the question to think of one as an exit portal to some altogether different configuration of space-time, some new cosmos even—I have for a long time now been unable to speak of God as a way out of this earthy world. Speaking of God seems rather to be a way into it, even if as an alien.

There, I have already said too much. My location is showing. Yet there is nothing surprising about that. Every college sophomore knows that God is tradition-specific. One opens the OED to the “G” tab and there one finds a meandering account of the roots of the little English word, roots that draw nutrients from deep inside pagan soil, where perhaps the ordinary usage of God is more happily at home. Provocative phrases about sacrifice and invocation appear in the midst of its history, their subjects and objects mingle, and in it all there is no outbreak into anything particularly transcendent (though transcendence as a universal within this system appears). Everything swims in the warm, immanent amniotic fluid of human consciousness. God as such is contained, subjected to occupational therapy at the merest suggestion of aphasia, and assigned the task to speak well in accordance with reasonable expectations. Thus God says something that is generally true, able to be heard everywhere and by all; a grand linguistic phenomenon, an absolute truth, the chief exemplification of all metaphysical principles, no doubt.

And yet the OED is not the only big book. At the “Job” tab, one finds a meandering account of a particularly poor and troubled man, who—sitting on the ash heap, alone but for the company of dogs, aching, burning, and with every new upset tempted to curse God and die—turns his two wide eyes to the open sky and with a passion that rips apart the fabric of space-time and its God cries, “Violence!” (Job 19:7) and as if encountering something new on the far side of the sun, prophesies, “I know my redeemer lives” (Job 19:25; cf. Eccl 1:9). And I read that with him on the ash heap—in a maelstrom so fierce that even Job’s immeasurable suffering seems a shadow cast from what is for him yet to come—another poor and lonely man, hanging, dying, gasping for air, opens his throat and cries, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34); and when “the curtain of the temple [is] torn in two . . . [as if encountering something new on the far side of death and damnation], Jesus, crying with a load voice, [prophesies], ‘Father, into your hands I commend my spirit’” (Luke 23:45–46). It strikes me that there is uttered in these narratives a word that no sequence of letters, however small or large, can contain. And I strain to say this new word when I stand before a classroom full of the children of good people, I strain to say it in such a way that no good person could ever say or hear it. And likely, were I just able to find a really good therapist, I’d put this obsession behind me and get on with my life.

The question for me then is “why, why do I see and hear this way?” Most of my colleagues these past decades have seen and heard differently. They seem much calmer about it all, speaking as they do of the good, the true, and the beautiful and of how God fits so well into a system of values, goals, and ideals, i.e., a worldview; of how the story of Job and of Jesus and of God is a story that resolves questions, not complicates and ruptures them. They have told me that it is all about absolutes and universals and all I seem ever to see and hear are contextualized particulars, the life-stories of people with particular faces and voices, of a God with particularly elusive faces and voices. Of course, it may just be that I have been beguiled by Protestant nominalism, that I have fallen prey to that most modern of all perversions, postmodernism, that I am a child of my age. Indeed, I suppose this is all true. How could I honestly say anything else, even as I strain to say something else than the banal or high-born talk of my age?

My journey has been a particular one, too, of course. Everyone’s is. I don’t understand much of it. It is not over, after all. Yet I would venture to say that it is the way I have been given and made time, the way I have come to let time go, the timely way I have begun to be named. Whatever that tiny English pronoun—I—might signify in this case, the thinking and speaking and working attached to it happen here, in this story. And it isn’t just my story.91 I’m not even sure I qualify for a best supporting actor nomination.

It is not insignificant that my hard Scots-Irish ancestors92 cut their way across an ocean and the rivers and forests of a forbidding New World to reach for the promises they’d heard were hidden under the cruel Appalachian Mountains of eighteenth-century Virginia, or the cruel Ozark Mountains of mid-nineteenth-century Arkansas, or the cruel hills of late nineteenth-century Oklahoma; that both my parents were raised in abject poverty by single mothers93 just to the southeast of the official borders of the Great Depression’s Dust Bowl; that I am an only child; that I attended nine schools before I went away to college; that I was eighteen in 1968; that in the summer of that year, while reading the book of Acts in the Desert Southwest, I became a pacifist; that the theologians I first threw myself into were Søren Kierkegaard and John Wesley—no theologians at all, the Hollywood Foreign Press would tell us; that I have spent my life among Holiness people; that I still think about the lyrics to Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”; that I am an ordained deacon and not an elder; that I have been married over forty years, have three children and six grandchildren; that my parents, now in their nineties, live with us; that I have had already a long career as a professor in four private, self-consciously evangelical universities; and that I know how to be alone.

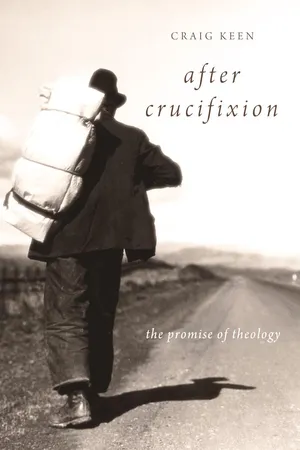

Perhaps it is all of that which inclines me on a brisk spring morning—obligated to stay put, though these days I am—to make my way to a tall, broad, clear window and there to dream of the open road.94 Perhaps it is all of that which inclines me to make my way to an icon—written with bright pigments across a salvaged plank of wood or in the interplay of the black and white on a printer’s acid-free rice paper or between the lines and words and along the margins of the credos of saints and sinners or upon the tales of liturgically martyred mothers and fathers or in, with, and under the playful work of the eating and drinking of bread and wine—and there to dream of God.95

And yet a dream of God—this God—is no ordinary dream, nor night terror, as Daniel and John the Revelator teach us. It is an apocalyptic vision. As such it makes manifest what good people do not want to see, perhaps cannot see. It manifests above all that there is a tomorrow that no yesterday can dictate.96 But it does so with the ambiguity that accompanies ...