1

Cream Puff Jesus

The Christ of Liberalism

The Bible is both inspired and covered with human fingerprints—but the Bible is not what we worship. The God to which the Bible points us is what we worship, and the claim of the first followers of Jesus was not that he was God, but rather that he revealed the fullness of God at work in a human being.

Robin Meyers

My mother-in-law is an extraordinary cook. She does with a spatula what fairy godmothers do with wands. She moves it here and waves it there, tosses in a dash of this and a dab of that and—bibbity bobbity boom!—a delicious delight springs to life and flour lies like fairy dust all about. When I am fortunate enough to be around her I like to take part in the fruits of her labor and eat my fill. (Okay, so it’s not just when I am around her, but that’s not the point.) My visits to the in-laws often mean two things for my diet: first, I will be in food-heaven for a week or so; and second, my caloric intake is going to take a serious hit. Oh, make no mistake, I’ll enjoy it all right. But, I’ll enjoy too much of it, and I’ll start seeing the margin between the two numbers on my jeans size widening. That’s never good. So I’ve got to be careful and do what I am not predisposed to do: to eat for sustenance more than I do for pleasure. I need to be a calorie counter rather than a calorie container. My problem, like most people in the western world, is that I am more driven by the taste of the food than by the truth about the food. The last thing I want to hear as I am watching the game and downing my favorite chips or ice cream is how many calories each serving has. Truth is not exactly on my radar screen as I tickle my taste buds and satiate my momentary urges with recreational snacking that ultimately pollutes my body and leaves me less satisfied and more wanting than when I started indulging. If only such self-indulging vices were limited to our physical diets! But, the hard and more dangerous fact is: they are not.

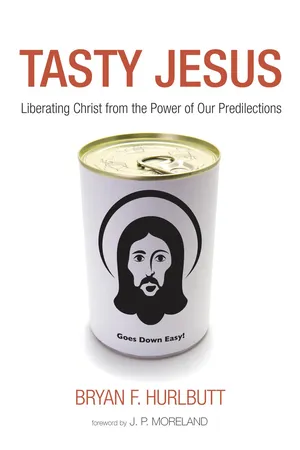

Unhealthy ideologies pollute the soul just like unhealthy food pollutes the body. And, tragically, just like the unhealthiest of foods are often the most savory, so are some of the most toxic of ideas that contaminate the soul the most delightful to our thoughts and feelings. They only ask of our wills that which we already desire to give. This fact rears its head and licks its chops when we come to the subject matter of the theologically liberal vision of Jesus. I would characterize this vision as a cream puff, a Jesus devoid of his deity and vacated of his supernatural power. This Christ has little to offer the church and less to offer the world.

The subject of this chapter ought to be of great concern to every thinking Christian that values their spiritual heritage and holds biblical orthodoxy with any sort of vigor. However, my fear, quite frankly, is that we are content to let the contemporary apostles of a liberal Jesus roam about preaching and proclaiming their christological cream puff and simply leave the rebuttals in the charge of seminary-level academics. While I have great regard for and have learned much at the knees of these great minds, I have grown weary of the local church’s inability to stand for truth intelligently amid the poisons of our culture. The local church is the institution that God has chosen to use in advancing his kingdom. But that advancement is being halted by the ineptitude of Bible-believing local church leaders and attendees to respond to the repeated hijackings of their savior and redeemer. Enough is enough! In this particular case, the Bride of Christ must clearly and resolutely defend the honor of her groom as he is made out to be a spiritually benign social reformer more interested in rejecting political oppression under Caesar than proclaiming eternal reconciliation with God; or, a sage whose pithy guru-like wisdom serves as a sort of ancient life coach on society’s tumultuous seas. This liberal cream puff may taste great, but he is high in spiritual calories and ultimately destructive to the individual soul—and to the church at large.

Our goal in this chapter is to get a handle on just how this cream puff emerged in western thought. If the church is to deal with the liberal Christ then she must clearly grasp from whence this vision came. To accomplish our goal we will take three steps: First, we will look at a brief sketch of some major contributors to this tasty Jesus. Second, we will get a crystallized picture of this contemporary cream puff. Finally, we will gain an understanding of the underlying appetite that has generated this theological craving.

The Historical Ingredients of a Christological Cream Puff

Ideas, like babies, never come down in the mouth of a stork. They come to us through a long history of thought, dialogue, and debate. They are shaped and formed by great minds from diverse intellectual disciplines and often take years to crystallize into a moderately coherent framework of ideas. The theological liberalism of today is no different. Scholars did not wake up one morning and decide to create a particular view of Jesus. Many of them are not devilish men purposely swept up in a sinister scheme to overthrow the biblical Jesus (we will leave all bizarre historical theology conspiracies to the Dan Browns of the world). Instead these scholars are the product of a heritage of thinking that has come down to us over the past 200–250 years. I do not intend to champion their innocence—far from it. But scholars are not immune to pre-commitments. They do not come into the marketplace of ideas with a tabula rasa, as it were. The recipe for the creation of this christological cream puff, two centuries in the making, includes philosophical, theological, and cultural ingredients. These ingredients combine to form a tasty Jesus who is high in concentrated spiritual fat and ultimately bad for the health of any who are buying what he is selling.

A Dash of Kant

When I attended Dallas Theological Seminary, I concentrated my studies in historical theology and had the privilege of sitting under the instruction of Dr. John Hannah. Dr. Hannah’s vast knowledge of the historical development and flow of Christian doctrine was only matched by his rapier wit. One time in class, as we began our study of modern liberal theology, he shared with us that if one could, hypothetically, turn Germany upside down, the bottom would read “Made in Hell.” His humorous insight was actually deeply poignant. Many of the most dangerous ideas that have impacted the western world in the last two hundred years had been given intellectual birth in German lecture halls by way of Enlightenment and Post-Enlightenment thinkers.

The Age of Enlightenment was the nineteenth-century child of two married movements. The first parent of Enlightenment thinking was a great cultural movement known as the Renaissance. The Renaissance was an artistic and scientific revolution that captivated the life of the western world from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. It is no exaggeration to say that the advances in creative expression and scientific knowledge brought by this shift forever changed the way we as humans see the world. The spouse of the Renaissance was a sixteenth-century theological movement known as the Protestant Reformation. Through the Reformation, spiritual freedom was achieved as the theological tyranny of the medieval Roman Catholic Church was broken. Under the guise of men like William Tyndale and Martin Luther, laymen were liberated to read the Bible in their own vernacular tongues. No longer were the Scriptures privatized by the clergy in Latin. No longer were the common people held captive to the rule of prelates, priests, and popes. Led by theologians like Philip Melanchthon, John Calvin, and Theodore Beza, the cumbersome weight of unbiblical tradition began to be lifted, and a reformation of theology was birthed.

This marriage of the Renaissance and the Reformation created an ethos rife with a sense of spiritual liberty, personal autonomy, and intellectual independence. As this atmosphere settled in over the next two centuries, a perfect storm began to take shape for the genesis of the Age of Enlightenment under the brilliance of that age’s greatest thinker: the German, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). Kant’s thought set the stage for the next two hundred years of western intellectual life. It would be almost impossible to overestimate his importance to the way that we see the world.

In short, we should understand Kant as a synthesizer of competing philosophies. In his era he stood at a point of convergence, bringing together two modes of thinking. One was called Rationalism and the other Empiricism. The former saw that reality was apprehended accurately by the mind and is often linked with the great Catholic thinker René Descartes (1596–1650). Descartes determined that the only thing that could not be doubted in the world was the fact that he had the mental processes of thought. Thus stands his famous utterance, “I think, therefore I am.” He rooted his existence in the fact that he had clear and distinct thoughts. Reason, our modes of thought or rational capacities, became, for Descartes and many others, the most reliable aspect of our existence, indeed the very manner in which we could verify our existence at all.

Set opposite the mindset of the rationalists was that of the empiricists. The great empirical thinkers were men such as John Locke (1632–1704), David Hume (1711–1776), and George Berkeley (1685–1753). Empiricist philosophy understood the world to be a sense-apprehended and sense-interpreted reality. To ask, for example, if a chair exists, is in many ways a silly question to an empiricist. The question could only be answered by saying “I see a chair.” For the empiricist, the world is sense-dependent. It can only be talked about in terms of subjective personal apprehension, not in terms of objective sense-independent existence. The empiricist’s sense of the world is all they can ultimately speak about with any confidence.

On the heels of the rationalist thinkers on the one hand and the empiricist thinkers on the other comes Kant. His approach to looki...