1

Sennacherib’s Campaign to Judah

The Events at Lachish and Jerusalem

David Ussishkin

A. The Assyrian Campaign

Lachish and Jerusalem were the most important cities which were militarily challenged by Sennacherib during his campaign to Judah in 701 B.C.E. The events that transpired in these cities are documented in the historical chronicles, and their material remains have systematically been studied by archaeologists. In the case of both cities an analysis of the archaeological data helps in interpreting the written sources and in understanding better the events of 701 B.C.E.

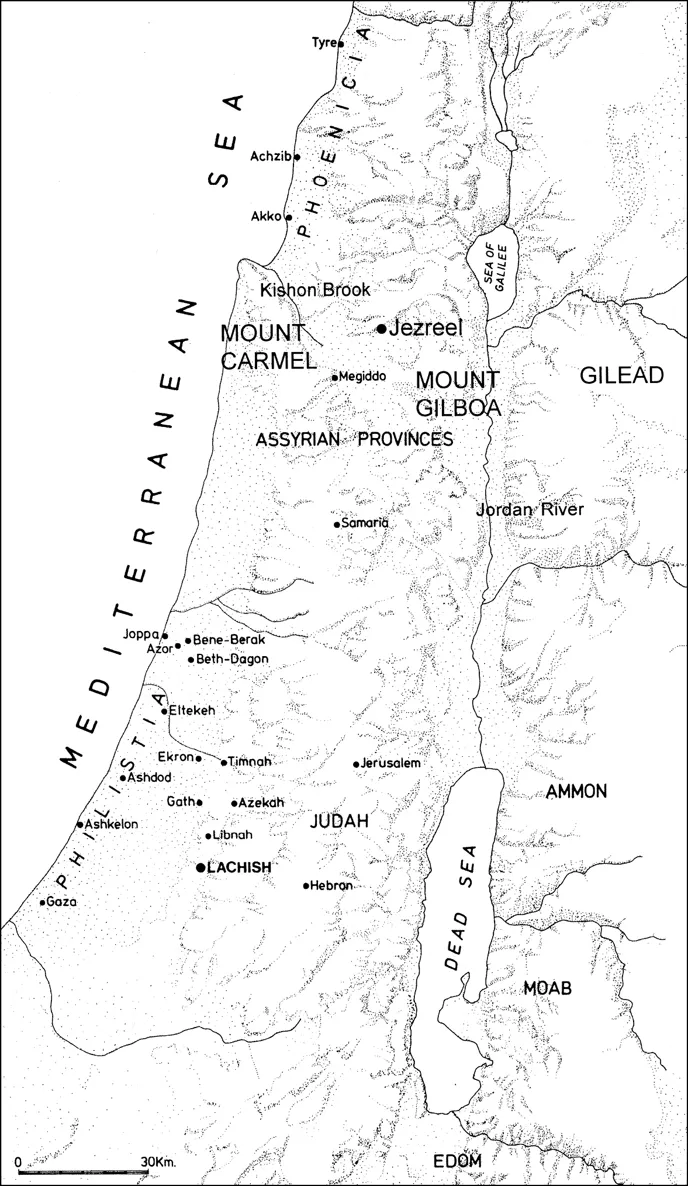

In 705 B.C.E. Sennacherib ascended to the throne of Assyria, which at that time was the largest and most powerful kingdom in the Near East. The young king was soon faced with a revolt organized by Hezekiah king of Judah. An alliance against Assyria was formed between Judah, Egypt and the Philistine cities in the Coastal Plain, possibly with Babylonian support. Sennacherib met the challenge. In 701 B.C.E. he marched to Phoenicia, Philistia, and Judah, and succeeded in reestablishing Assyrian supremacy in those regions (see map in Fig. 1).

Based on the detailed information in the Old Testament and the

Assyrian records it seems that the main course of the campaign can be reconstructed in different ways. The following reconstruction seems to us the most plausible. Sennacherib and his powerful army marched on foot from Nineveh, the capital of Assyria to the Phoenician cities situated along the Mediterranean coast (see map in Fig. 1). Sennacherib received there the tribute of various vassal kings and continued his advance southwards to Philistia. He then defeated in open battle a large Egyptian expeditionary force, and reestablished Assyrian rule in Philistia.

Fig. 1. The ancient Near East at the end of the eighth century B.C.E.

At this point Sennacherib turned against Judah and its ruler Hezekiah (see map in Fig. 2). It is clear that upon arriving in Judah, Sennacherib’s attention was focused primarily on the city of Lachish rather than on the capital Jerusalem. Lachish was the most formidable fortress city in Judah, and its conquest and destruction were the paramount task facing Sennacherib when he came to crush the military powers of Hezekiah. In fact, the conquest of Lachish was of singular importance and a great Assyrian military achievement as indicated by the Lachish reliefs (see below).

The Old Testament informs us that Sennacherib encamped at Lachish and established his headquarters there during his campaign in Judah (2 Kgs 18:14, 17; Isa 36:2; 2 Chr 32:9). He conquered and destroyed forty-six Judean cities, and from Lachish he sent a task force to challenge Hezekiah in Jerusalem. Eventually, as related in both the Old Testament and the Assyrian annals, Jerusalem was spared, and Hezekiah, who came to terms with Sennacherib, continued to rule Judah as an Assyrian vassal, and paid heavy tribute to the Assyrian king.

A detailed account of the Assyrian campaign in Judah is given in the biblical texts, focusing on the events in Jerusalem (2 Kgs 18–19; Isa 36–37; 2 Chr 32). It should be noted that the prophet Isaiah played a significant moral and political role in solving this acute crisis, the most difficult one during the reign of Hezekiah.

Fig. 2. The Land of Israel at the end of the eighth century B.C.E.

B. Biblical Lachish: The Judean Fortress city

Turning to Tel Lachish, the site of the biblical city, we see that it is one of the largest and most prominent mounds in southern Israel (Fig. 3). The mound is nearly rectangular, its flat summit covering about eighteen acres. The slopes of the mound are very steep due to the massive fortifications of the ancient city constructed here.

Fig. 3. Tel Lachish, the site of biblical Lachish, from the north.

Extensive excavations were carried out at Lachish by three expeditions. The first excavations were conducted on a large scale by a British expedition, directed by James Starkey, between 1932 and 1938. The excavation came to end in 1938 when Starkey was murdered by Arab bandits. The excavation reports were later published by his assistant, Olga Tufnell. In 1966 and 1968 Yohanan Aharoni conducted a small excavation, limited in scope and scale, in the Solar Shrine of the Persian period (Fig. 4 no. 11). Finally, systematic, long-term and large-scale excavations were directed by me on behalf of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University between 1972 and 1993.

Lachish was continuously settled between the Chalcolithic period in the fourth millennium and the Hellenistic period in the third century B.C.E. Our concern here, however, is the city of Levels IV and III, dated to the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E. respectively.

At the beginning of the ninth century B.C.E. one of the kings of Judah constructed here a formidable fortress city, turning Lachish into the most important city in Judah after Jerusalem. With the lack of inscriptions it is not known who is the king who built the city and at what date. The fortress city continued to serve as the main royal fortress of the kings of Judah until its destruction by Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E. In archaeological terminology this fortress city is divided into two successive strata, labeled Level IV and Level III.

The plan in Fig. 4 shows the outlines of the fortress city, and the illustration in Fig. 5 portrays a reconstruction of Lachish from the west on the eve of Sennacherib’s conquest in 701 B.C.E.

Fig. 4. Plan of Tel Lachish: (1) Outer city-gate; (2) Inner city-gate; (3) Outer revetment; (4) Main city-wall; (5) Judean palace-fort complex; (6) Area S—the main excavation trench; (7) The Great Shaft; (8) The well; (9) Assyrian siege-ramp; (10) The counter-ramp; (11) Acropolis Temple; (12) Solar Shrine; (13) Fosse Temple.

Fig. 5. Reconstruction of Lachish on the eve of Sennacherib’s siege, from west; prepared by Judith Dekel from a sketch by H. H. McWilliams in 1933, supplemented by newly excavated data.

The nearly rectangular fortress city was protected by two city-walls —an outer revetment surrounding the site at mid-slope (Fig. 4 no. 3), and the main city-wall, extending along the upper periphery of the site (Fig. 4 no. 4). The massive outer revetment was uncovered in its entirety by the British expedition. Only its lower part, built of stones, was preserved. It probably served mainly to support a rampart or glacis, which in turn reached the bottom of the main city-wall. The main city-wall was built of mud-brick on stone foundations. It was a massive wall. Being more than 6 m or about 20 ft thick, its top provided sufficient, spacious room for the defenders to stand and fight.

A roadway led from the south-west corner of the site to the gate. The city-gate complex included in fact two gates: the outer gate (Fig. 4 no. 1), connected to the outer revetment, and the inner gate (Fig. 4 no. 2), connected to the main city-wall, and an open, spacious courtyard between the two gat...