![]()

1

Introduction

“Without the Camp”

hebrews 13:11

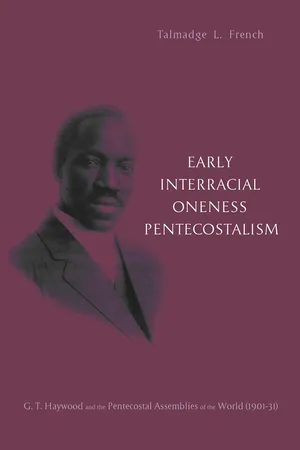

Perhaps the least known chapter in the history of American Pentecostalism is that of early Oneness Pentecostalism. The earliest era of this segment of the movement (1901–31) is especially relevant to Pentecostal history in general because of its unique and durative display of interracial fervor, an impulse which figured prominently into its formative development. This book is an in-depth look at the history and nature of this initial interracial vision as interpreted via the lens of one of the movement’s primary architects, Garfield Thomas Haywood, and within the early development of Oneness Pentecostalism’s central church and ministerial structures, the interracial Pentecostal Assemblies of the World.

It is also an attempt to rectify a one dimensional historical perspective currently pervasive in the overall historiography of Pentecostalism, and, therefore, decidedly inclusive of its Oneness dimensions, on the one hand, and a balance, on the other hand, to common interpretive models which have ignored the significance of race in the restorative framework of the early movement. As a starting point it is essential to trace this interracial fervor into the Azusa Street revival and to account for the Parham-influenced, power-struggle resistance to this impulse in the U.S. regionally. Several significant pieces of the historical puzzle have come to light in this research which give fresh and, in some cases, ground breaking insight into the events, such as the 1906 Azusa Street Mission founding of the interracial Pentecostal Assemblies of the World.

These and other sources have contributed to a much better understanding now of two of Oneness Pentecostalism’s most obscure early leaders, J. J. Frazee and E. W. Doak, as well as of the movement’s early major centers. African American Pentecostal leader G. T. Haywood, as it turns out, figures most prominently into this history, not only as one of its leading proponents, but as its central interracial voice, as well as its most renowned leader in its foremost early epicenter—Indianapolis, Indiana.

Therefore, an examination of its interracial authenticity necessitates an extensive look into the pre-Oneness context of the PAW, the related battle for the newly organized, intricately related, Assemblies of God, and the transition of the PAW itself from “Trinitarian” to “Oneness” Pentecostalism. In the final analysis this book makes an effort at investigation into the whole scope of the eventual racial schism which came to Oneness Pentecostalism and to the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World, in particular, in 1924, resulting in a majority withdrawal of the White segment of churches and ministers. The resulting rejection of the interracial impulse which followed within Oneness Pentecostalism as a whole produced a fractured movement with decades of resulting diffusion and the proliferation of separatism and independency. These events marked, indelibly, the movement’s regional development in the U.S., as well as its critical global missionary and autochthonous segments, all of which were expanding rapidly by 1930.

1.1 Definitions and Parameters

The making of Oneness Pentecostalism, like that of the broader movement to which it is a prominent part, was largely dependent upon the motifs of restoration and revelation within its earliest development.1 In turn, these elements greatly impacted its own theological receptivity to an early interracial impulse which largely shaped Oneness Pentecostal ideology for more than a generation. Yet it may very well have been equally impacted by the nature of the theological isolation and rejection experienced as a result of its theological position, although it developed parallel to, if isolated from, broader forms of Pentecostalism.

The salient and emotive remarks of G. T. Haywood, for example, in the December 1916 issue of his influential periodical The Voice in the Wilderness, contain an excellent metaphor descriptive of the Oneness movement. They reveal his response to the events of October 1916—the resulting traumatic expulsion of the Oneness ministers from the young Pentecostal ministerial body in St. Louis known as the Assemblies of God:

There were quite a number who withdrew from the Council at the close of the session, because there was a spirit of drifting into another denomination manifested, when they began to draw up a “creed,” which they termed “fundamentals.” It is no doubt the same thing under a different name. I have no complaints to make, but by the grace of God I shall endeavor to press on with the Lord “without the camp, bearing His reproach, for here we have no continuing city, but we seek one to come.”2

Oneness Pentecostalism, the term which has become the most popular designation for the movement, and the term of preference in this book, is known also as the Apostolic Pentecostal and as the Jesus’ Name movement, all being equally acceptable common self-designations. From its inception the movement has, indeed, remained “without the camp,” as an enigma, and as a Pentecostal antagonist to the broader movement, experiencing both imposed and self-imposed isolation from the religious mainstream. This has been due largely to rigidity in its deviations from the classical doctrine of the Trinity and its soteriology.

Haywood’s use, nonetheless, of such an Old Testament “without the camp” analogy encompassed more than the mere theological rejection of the Assemblies of God. It was, in fact, intricately linked as well to the AG racial rejection.3 Some months prior to Haywood’s remarks and the AG expulsion of its Oneness element in October 1916, well-known Pentecostal songwriter Thoro Harris also startled his AG Council compatriots by converting to the Jesus’ Name movement. As a rallying cry for the cause he immediately wrote “Baptized in Jesus’ Name,” and, in 1917, penned his most familiar of hymns, “All That Thrills My Soul Is Jesus.” His baptismal hymn opens defiantly: “Today I gladly bear the bitter cross of scorn, reproach and shame; I count the worthless praise of men but loss, baptized in Jesus’ Name.”4

The Oneness proponents seemed to rather gladly identify such reproach with the suffering required for His Name, a theme which would loom large in Jesus’ Name Pentecostalism. And, as Haywood vividly symbolized, their very identity was defined by a suffering “without the gate,” a w...