![]()

1

“EXPLORATION INTO GOD”

The Doctrine of God and God’s Ministry

Ray Anderson suggests that whenever we write the name of God on the chalkboard (or PowerPoint!) we should then step back and see if we survive! To speak of God is an awesome thing. Too often glib theologians and confident ministers may too easily speak of the divine. Should this lead us to agnosticism, or at least a halting skepticism about any knowledge of God? What, instead, if we began to speak of God in terms of ministry?

But is this right? If we ever speak of the ministry, of the church, the sacraments, etc. then should that not be based on thoroughgoing and convincing arguments for the existence of God and explicit knowledge of God’s nature? Ray Anderson has an alternative.

All Ministry is God’s Ministry

To speak of the ministry of God means to speak of the God who acts. Every Bible-believing Christian adheres to this. But so often we interpret ministry as only our part, which we do after God has acted. Isn’t it more biblical to speak of ministry as something that, in the first instance, God does? “All ministry is first of all God’s ministry.”

God acts in creation and then in Israel. These acts are the ministry of God. The general ministry of God in creation becomes particular and specific in the election of Israel. “Revelation is not just the Word of God to Abraham; it is Abraham.” Abraham is not just the object of revelation, he is now a part of the ministry of God. What distinguishes the God of Israel from the false gods is that the God of Abraham is the creator who acts (Ps 135:18), the one who possesses a ministry. The God of Abraham is the God who acts, who has a ministry.

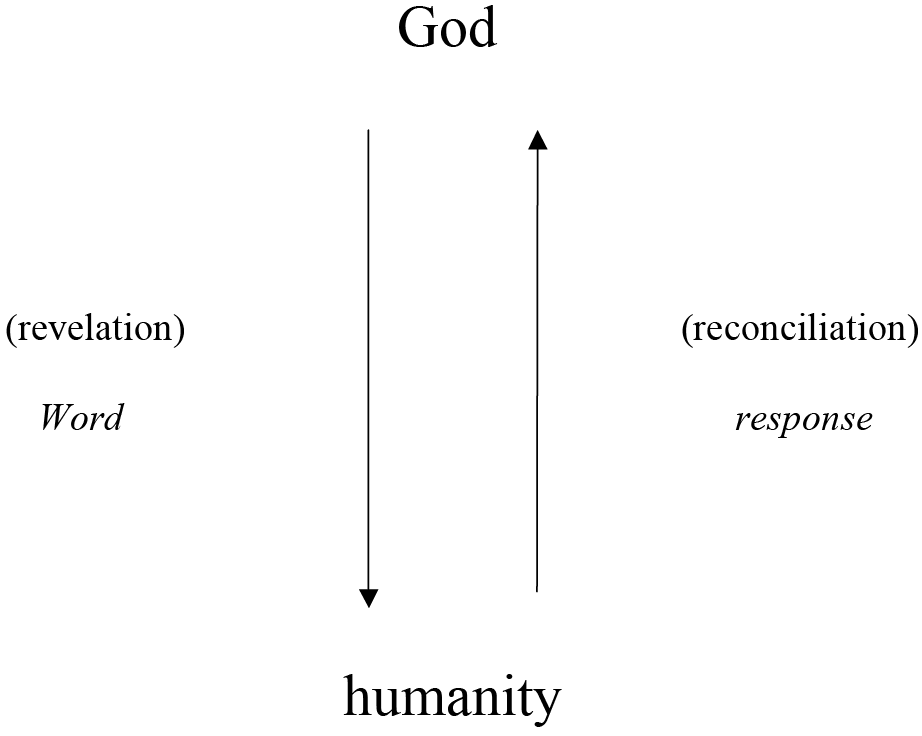

In that same seminal essay, “A Theology for Ministry,” Anderson speaks of ministry as both “revelation and reconciliation.” Building upon Karl Barth’s and T. F. Torrance’s critique of Cartesian and Kantian influences on modern theology, Anderson argues for regarding revelation and reconciliation as “reciprocal movements of a single event.”

Figure 1

God is on “both sides” of revelation and reconciliation—not just knowing God through revelation (the attention of the Cartesian and Kantian agendas), but through the ministry of reconciliation as well. That God is on the side of reconciliation as well as revelation will be important for Anderson when he appropriates T. F. Torrance’s doctrine of the vicarious humanity, not just the death, of Christ. Yet Anderson is careful to make it clear that reconciliation is not a movement that originates with the fall of humankind, but that which is integral to the endowment of the imago Dei, the image of God in humanity (Gen 1:26–27). “The human response does not condition or determine the divine Word, for the Word has itself a divine correspondence by virtue of the image of God through which Adam knows himself.”

Yet there is a ministry of “judgment and grace” to the solitary male Adam, in the first “not good” of the Bible (prior to the fall in Gen 3): “It is not good that the man should be alone” (Gen 2:18). God does the ministry of that which is impossible. “It is only when the single male is put to sleep and the creative Word itself operates in such a way that the divine likeness and endowment is divided into a complementary existence, that that possibility is actualized. Out of impossibility, God’s Word becomes God’s ministry.” Adam now exclaims, “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” when Eve is created (Gen 2:23). Both judgment and grace are found here, Anderson argues. “This grace of God is a verdict rendered upon every attempt to circumvent that Word and to provide an alternative response. It is revelation that provides reconciliation. God’s ministry takes what is impossible and creates possibility.” But in doing so, Anderson hastens to maintain the place of human participation. “But it does this in such a way that the creature himself is incorporated into the new possibility. It is ‘bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh.’ Adam is not himself set aside. There is no judgment against him, but a judgment for him and against all that would only inevitably betray and fail him.”

Our understanding of the nature of God, our doctrine of God should be shaped by God’s ministry, Anderson contends. Where else, apart from God’s activity in Israel and in Christ, do we get our doctrine of God? The greatest possible being we can think of? A great designer? A source of morality? No! From the story of God-at-work in Israel and in Christ.

Anderson finds the meaning of God’s ministry in the seventh day (the Sabbath), the “special word of revelation from God.” Through the Sabbath, the meaning of the first six days are revealed. “In this way, one can say, theologically, that the seventh day precedes the sixth day. In the same way, God’s ministry precedes our concepts of God. It is through God’s ministry of redemption that we understand the meaning of God’s work as Creator.” Without the Sabbath, the seventh day, we are left with only the six days, the days of nature, the days of the workaday world in which nature determines destiny, in which our jobs, for example, can determine wholly who we are. A concept of a God of nature or destiny can unfortunately be brought into the church. It is different when the seventh day theologically precedes the first six days, Anderson suggests. Therefore, our concepts of God are judged, a God of our morality or our culture, something that makes us very uncomfortable.

God’s ministry reaches its fruition in Jesus Christ, the perfect manifestation of ministry as revelation and reconciliation in the one event ...