- 324 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

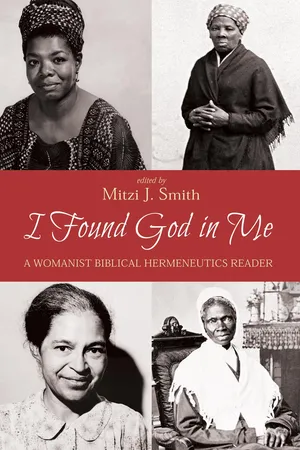

I Found God in Me is the first womanist biblical hermeneutics reader. In it readers have access, in one volume, to articles on womanist interpretative theories and theology as well as cutting-edge womanist readings of biblical texts by womanist biblical scholars. This book is an excellent resource for women of color, pastors, and seminarians interested in relevant readings of the biblical text, as well as scholars and teachers teaching courses in womanist biblical hermeneutics, feminist interpretation, African American hermeneutics, and biblical courses that value diversity and dialogue as crucial to excellent pedagogy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Found God in Me by Mitzi J. Smith, Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Womanist Interpretations of the New Testament

The Quest for Holistic and Inclusive Translation and Interpretation28

The subject of “womanist biblical interpretation” has come to the fore in recent years in conjunction with the growing body of literature on “womanist theology” in general. The term “womanist” was coined by Alice Walker in her book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. Describing the courageous, audacious, and “in charge” behavior of the black woman, the term “womanist” affirms black women’s connection with both feminism and with the history, culture, and religion of the African American community. Womanist literature represents the ongoing academic work of womanist scholars in a variety of disciplines, including theology, ethics, sociology, and biblical studies.29

One discipline where womanist theological reflection is especially welcome is biblical studies. What concerns do womanist biblical interpreters bring to the translation and interpretation of the Bible? How does their interrogation of the text differ from that of their white feminist colleagues? These questions will be explored in this essay in preliminary fashion. Not meant to be an ultimatum verbum (the last word) for all womanist biblical scholars, but only primum verbum (first word) by one, it highlights some of the critical and methodological concerns and overarching interests of womanist biblical interpreters.

If, as theologian Delores Williams notes, womanist theologians bring black women’s social, religious, and cultural experience into the discourse of theology, ethics, and religious studies,30 they also bring black women’s social, religious, and cultural experience and consciousness into the discourse of biblical studies. Thus, African American women’s historical struggles against racial and gender oppression, as well as against the variegated experiences of classism, all comprise constitutive elements in their conceptual and interpretive horizon and hermeneutics; for experiences of oppression, like all human experience, affect the way in which women decode sacred and secular reality.31

In addition to importing gender, race, and class concerns to the task of biblical interpretation, womanist theologians have addressed the issue of linguistic sexism with increasing urgency.32 Womanist biblical interpretation, then, has a “quadruocentric” interest (“four-fold,” from the Latin quadru, meaning “four”) where gender, race, class, and language issues are all at the forefront of translation (the science of expressing the original meaning as accurately as possible) and interpretation (the process of bringing together the ancient canonical texts with new, changing situations) concerns,33 and not just a threefold focus where gender, class, and language concerns predominate almost exclusively, as is often the case in white feminist biblical interpretation and translation.

In this essay I will examine the ways in which womanist concerns about the translation and interpretation of biblical terminology are focused. I will also examine the ways in which presuppositions about the significance of class in biblical narrative have been operative in contemporary biblical interpretation.

Doulos, Doule: Servant or Slave?

The tremendous proliferation of literature on inclusive language in ecclesial and academic discourse in recent decades34 has reawakened our interest in the complexities of the translation of biblical terminology. Assessing the appropriate meaning of a particular Hebrew or Greek term, and rendering it with some fidelity in English, remains a thorny problem for interpreters. For example, the King James Version of the Bible describes Jesus and his disciples as walking “through the corn” in Matt 12:1. As they walked, they began to “pluck the ears of corn to eat.” The twentieth-century student of the Bible may be tempted to imagine the itinerate group “strolling through a cornfield, stripping off a ripening cob, pulling back the husk and silk, to nibble on the tender kernels.”35 But in fact, the Greek term for “corn,” stachys, should probably be rendered “grain,” as it is in the Revised Standard Version of the Bible (the RSV uses the phrases “grainfields” and “heads of grain” respectively in Matt 12:1). “Grain” in biblical usage is a generic term used to indicate the seed of cultivated cereal grasses such as wheat, barley, millet, and sorghum (these grains were ground into flour as a major component of bread products—compare Deut 33:28 in the KJV and the RSV).36

One of the more debated translation issues is the translation of the Greek term anthropos. Translators have regularly rendered anthropos as “man,” concealing women or rendering them invisible under a blanket of male linguistic hegemony. Like blacks who must constantly “imagine” themselves as represented in so-called generic representation of Americans by all white groupings (whether on television or in other media) women must constantly “imagine” themselves as represented in so-called generic representations of all humanity in biblical traditions that are punctured by the almost exclusive usage of male gendered pronouns. The real point, of course, is that anthropos does not always mean “man” or “men.” As had been amply demonstrated (and as some common sense would dictate) anthropos does have a more generic meaning. It can mean “human, person, people, or humanity.”37 The Oxford Annotated RSV does grant this sense in the translation of Rom 2:9: “There will be tribulation and distress for every human who does evil.” According to the Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament, anthropos also has a generic meaning in Matt 5:13, but the RSV translates the term as “man” when it records the familiar words:

You are salt of the earth; but if the salt has lost its taste, how shall its saltiness be restored? It is no longer good for anything except to be thrown out and trodden under foot by men. (Italics mine.)

Surely the more generic usage of anthropos is indicated and appropriate in the Oxford Annotated Bible for such texts as the Matt 5:13 pericope, as well as for such texts as Titus 2: “the grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men”; the text in 1 Tim 2:4, which says: “God desires all then to be saved”; and 1 Tim 4:10: “we have our hope set on the living God who is the Savior of all men, especially of those who believe.” Nance Hardesty hits the mark when she says of the androcentric rendering of anthropos in these verses in the RVS, that the God described in those passages “does not offer much hope for me as a woman!”38 The problem with these texts is that the translation of anthropos in these examples does not render in English what the Greek texts intended.

The task of faithfully rendering biblical terminology in English and assessing ideological import and sociopolitical impact on communities of women and men is a major concern to womanist biblical interpreters. This is particularly the case with the Greek term doulos, usually translated “slave.” As I have pursued my own research and study of the New Testament over the years, I have been asked frequently if doulos should be rendered “slave” or “servant” in modern translations of the Bible. The post-sixties era, with the rise of liberation theologies and the recognition of how one’s social location affects the interpretive task, has sharpened the question of how people of color and women “hear” certain t...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Permissions

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Womanist Interpretations of the New Testament

- Chapter 2: Re-Reading for Liberation

- Chapter 3: Womanist Interpretation and Preaching in the Black Church119

- Chapter 4: An African Methodology for South African Biblical Sciences

- Chapter 5: Marginalized People, Liberating Perspectives

- Chapter 6: Our Mothers’ Gardens

- Chapter 7: “This Little Light of Mine”

- Chapter 8: A Womanist Midrash on Zipporah

- Chapter 9: Fashioning Our Own Souls

- Chapter 10: A Womanist-Postcolonial Reading of the Samaritan Woman at the Well and Mary Magdalene at the Tomb

- Chapter 11: Minjung, the Black Masses, and the Global Imperative

- Chapter 12: Wisdom in the Garden

- Chapter 13: “Knowing More than is Good for One”

- Chapter 14: Silenced Struggles for Survival

- Chapter 15: “Give Them What You Have”

- Chapter 16: Acts 9:36–43