![]()

1

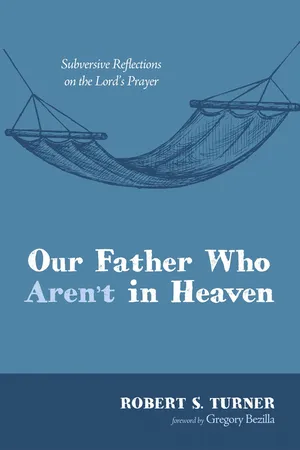

The Empty Hammock

Our Father who art in heaven . . .

I can’t put my finger on precisely when it first happened, but not that long ago, I heard myself utter a malapropism right there in worship one Sunday morning. As the senior pastor finished up the prayers of the people, he gave us the cue we had all been listening for: “ . . . as Jesus taught us to pray . . . ” and we launched into the Lord’s Prayer. With the rest of the congregation, I said, “Our Father who aren’t in heaven. . . .”

Wait a minute. What did I just say? It’s supposed to go, “Our Father who art in heaven.” Art. Not aren’t.

I found this slip of the tongue troubling, but in my defense, the wording of the original is pretty odd. If we updated it to modern English, we would say, “Our Father who are in heaven,” which would be grammatically incorrect. We would more properly say, “Our Father who is in heaven,” or, more concisely, “Our Father in heaven.” Instead, we can thank the translators who produced the King James Bible for bequeathing to us an antiquated and syntactically wrong phrase that has since lodged itself durably in the Christian lexicon.

Plus, it sounds a lot like “Our Father who aren’t in heaven”—an impious statement at best, if not a fully blasphemous one.

Or is it? As I thought about it (and now I can’t help but think about it every time I pray the Prayer), it struck me that there may be more truth to that verbal blunder than first appears. Far from denoting some kind of atheistic anti-creed, like the title of Christopher Hitchens’s book, God Is Not Great, it may actually say something profoundly apt about God.

Changing God’s Address

When I think of “Our Father who aren’t in heaven,” I recall one of the first scenes in Romero, the 1989 film about Oscar Romero, Archbishop of San Salvador, starring Raul Julia. The movie traces the progression of Romero from a bookish and fairly conservative Roman Catholic bishop to a firebrand preacher and activist. Converted to liberation theology, which proclaims that God has a “preferential option for the poor,” he seeks to empower the oppressed Salvadoran peasants in their struggle for justice. Romero’s embrace of this politically charged brand of theology leads directly to his assassination. Death squads in the employ of the government or the army or the oligarchy (precisely who ordered his murder has never been definitively established) shot and killed him as he celebrated the mass in March 1980.

In this early scene, Romero has gone with his friend, Father Rutilio Grande, to observe a voter registration drive led by some young people from Father Grande’s parish. While there, he overhears what to him sounds like radical, even sacrilegious talk, and he expresses to Father Grande his concern for him and his teaching. He says that some in the church have accused Grande of holding extreme views. Romero finds the idea so alarming that he stammers as he says it: “Some are saying that you are a sub-subversive.”

Grande replies, “Remember who else they called such names.” To make sure we don’t miss the point, he goes on to say, “Jesus is not in heaven somewhere lying in a hammock. He is down here, among his people, building a kingdom.”

Of course, Father Grande is exaggerating to make a point. If you pressed him, he would undoubtedly acknowledge the classic Christian affirmation that Jesus, following his resurrection and ascension, ascended to heaven and now sits “at the right hand of the Father.” Jesus is in heaven. God is in heaven. Yet with equal conviction we can say that in a powerful and important sense they aren’t in heaven. At least not lying in a hammock, as though they have finished their work and have nothing left to accomplish down here.

Saying “Our Father who aren’t in heaven,” then, does not deny the divinity or exaltation of God or Jesus. Rather, it affirms that they are not only there. When we imagine the heavenly location of God too rigidly, we run the risk of failing to see God at work on earth. But a short step from there lies Deism—the notion of God as a sort of absentee landlord, a Creator who set the world in motion according to scientifically discernible natural laws and then took a long lunch break and still hasn’t returned.

Planting God too firmly on some heavenly throne emphasizes the transcendence of God at the expense of God’s immanence. Christianity has always held these two attributes of God in balance. God indeed transcends all creation. We cannot comprehend God’s majesty. “[God] dwells in inapproachable light” (1 Tim 6:16). “The Lord, the Most High, is awesome, a great king over all the earth” (Ps 47:2). “How great thou art.” “A mighty fortress is our God.” The contemporary church, at least in North America, suffers from an overfamiliarity with God. It behooves us to maintain a vision of God as one “sitting on a throne, high and lofty . . . the hem of [whose] robe [fills] the temple” (Isa 6:1).

But the Christian faith has always held God’s transcendence in tension with a conviction of God’s nearness and accessibility. Throughout salvation history, God has always acted as the initiator. God approaches Abraham with the promise that he will be the ancestor of a great nation. God speaks to Moses face-to-face, as one speaks to a friend. God enters into an extravagant, passionate covenant with David. Finally, God comes into the world as a human being for the purpose of effecting our salvation once and for all. Add to all this the activity of the Holy Spirit, who moves within individuals and communities to continue the work Jesus began, and you have a picture of a God as close to us as our own skin.

To be accurate, then, we should say both, “Our Father who aren’t in heaven,” and, “Our Father who art in heaven.” God is both high and lifted up and intimately present with us.

Psalm 139 captures this dual reality in extraordinarily beautiful language. The psalmist extols the majesty and immensity of God’s being:

This God whose thoughts cannot be counted fills the whole universe, so that trying to get away from God’s presence is futile:

Those last two lines are telling. In spite of the absolute immensity and ubiquity of God, the psalmist does not hesitate to extol God’s closeness: “Your right hand will hold me fast.” This language of intimacy continues:

This intimate knowledge of God’s goes back even before the psalmist’s birth:

This magnificent psalm, with its deft interweaving of God’s transcendence and immanence, prefigures the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation. The prologue of the gospel of John, with its very high Christology, locates Jesus, whom John calls the Logos, or “Word,” with God before creation. John goes so far as to identify Christ with God: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through him, and without him not one thing came into being” (John 1:1–3a). That’s a pretty exalted view of Christ—as the very agent of creation and, indeed, as a full partner in the Godhead. As the Nicene Creed puts it, “The only Son of God . . . Light from Light, true God from true God.”

Yet the story John has to tell in his gospel will not allow Christ, the Logos, to remain in this transcendent state. Instead, “The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1:14 tniv). With this affirmation John leads us to the brink of one of the most powerful mysteries of our faith: how could Jesus be a mortal man but also God? Or, to put it another way, how could God enter into the human experience and still be God?

Jesus’s followers shared the conviction that something about their teacher set him apart from everyone else. They saw that the Spirit and Wisdom of God filled him in a unique way and they felt privileged to witness it—“We have seen his glory” (John 1:14). From these convictions developed the idea that later became the doctrine of the Incarnation. As the church of the first few centuries grappled with the question of how Jesus could be one with the Father—how the Word could not only be with God, but could also be God—the companion doctrine of the Trinity developed. These two mysteries, the most distinctive theological affirmations of the Christian faith, bring together the transcendence and immanence of God in a powerful way. God is high and lifted up, so we can say with conviction that God art in heaven. Because of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus—the Word become flesh—and the subsequent gift of the Holy Spirit, we can affirm simultaneously that God aren’t in heaven.

With the Incarnation, God in a sense filled out a change-of-address form. No longer could we conceive of God as distant, inscrutable, and inaccessible. No longer could we understand God as only transcendent, or as removed from the lives and concerns of God’s creatures. When God was born into the world as a human baby to human parents, whether in a house or in a cattle shed or under any other imaginable circumstances, God’s address changed. Or, more accurately, God established a dual residence.

Our Father who art in heaven.

Our Father who aren’t in heaven.

The Heaven Ghetto

As modern (or postmodern) people trying to read and interpret the Bible, we face the difficult challenge of removing many accumulated layers of tradition and misinterpretation to get to what the authors really meant. We have a tendency to forget that the Bible hails from the ancient world. Because many Americans still live in a religion-saturated culture, and because the Bible remains a perennial bestseller, we may perhaps be excused for thinking of it as a contemporary word for our contemporary times. After all, that’s what countless Sunday School classes and Bible study groups—at least in the evangelical world—encourage us to do: to learn how to “apply the truths of the Bible to our lives.”

This can be dangerous, however, if we fail...