![]()

1

Literary Relationships Among the Gospels

A Brief Introduction to the Synoptic Problem and Matthew and Luke’s Special Source Material

Introduction

Critical study of the Gospels and their sources is a complex endeavor, not least because of the sundry developments over the last century and the lack of complete agreement among scholars today. There have been numerous attempts to work out the difficulties surrounding the Gospels and while there was a time when a consensus seemed to have been reached, that is not the case today. Current research on the Synoptic Gospels and the “Synoptic Problem” is thriving. Old theories continue to be re-evaluated and refined, and fresh studies are helping to stimulate scholarly research and move the discussion into new, exciting directions.

The present book is meant to be a resource for the study of Matthew and Luke’s sources and will, I hope, be a useful guide to those learning about the Synoptic Gospels generally and about the Synoptic Problem and Matthew and Luke’s texts in particular. Since many will be coming to this subject for the first time, it will be helpful to provide a brief survey of the history of the Synoptic Problem before we move on to a discussion of Matthew and Luke’s special source material and the purpose of this book, since it is within this larger debate that the first and third Gospels’ special material was brought to light.

The Synoptic Problem

Today, the literary problem of understanding and explaining the literary relationships between the first three Gospels is known as the “Synoptic Problem.” Modern scholars have been dealing with this problem for many decades in an attempt to reconstruct the sources used in the composition of the Gospels. It should be noted, though, that modern biblical scholars are not to be credited with initially identifying the problems surrounding the Gospels and their sources. In the early church, some had begun to notice variations in the Gospels, such as, for example, Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount and Luke’s Sermon on the Plain. One of the earliest attempts to sort out these differences and inconsistencies was by Tatian (c. 125–185 CE), who produced a harmony of the four Gospels known as the Diatessaron (“through the four”), most likely in order to eliminate the discrepancies. The early fourth century church father Eusebius mentions that Africanus (c. 160–240 CE) wrote a letter (On the Supposed Discord between the Genealogies of Christ in Matthew and Luke) to Aristides in which he established a harmony of the two, divergent accounts of the genealogy of Jesus in Matthew and Luke. Augustine (354–430 CE) was the first person to make a serious effort to understand the literary relationships between the Gospels, and his approach was distinctly harmonistic. With respect to the order of the Gospels, he argued that Matthew was written first, then Mark, which used Matthew as a source, then Luke, which used both Mark and Matthew, and finally John, which used all three (the “Augustinian Hypothesis”). For centuries following Augustine, the critical debate experienced a hiatus, and the popular way to read the Gospels during this time was to conflate them, that is, to combine all the Gospel stories into one, big “meta-Gospel” much like Tatian’s Diatessaron. It was not until the eighteenth century that biblical scholars began to have a renewed interest in what Augustine and others had set out to do centuries prior, but this time the approach was much more critical and held to a higher level of scrutiny. During the Enlightenment (17th and 18th centuries), much of the work being done was centered on the life of Jesus and was driven by radical works that questioned the historical reliability of the Gospels, such as the “fragments” of Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768). Reimarus had proposed that the Gospels, since they were composed deliberately by the disciples to warrant their own stances of power, are unreliable sources for understanding Jesus. While Reimarus’ work was not well received among Christian scholars because of its radical assertions, it did force them into thinking objectively about the questions he raised and how to come up with possible solutions to the problems. In summary, this era experienced a development in Gospel research, and what began as a search for what can be known about the Jesus of history resulted in a critical examination of the primary sources that provided the information necessary for understanding him, namely, the Synoptic Gospels.

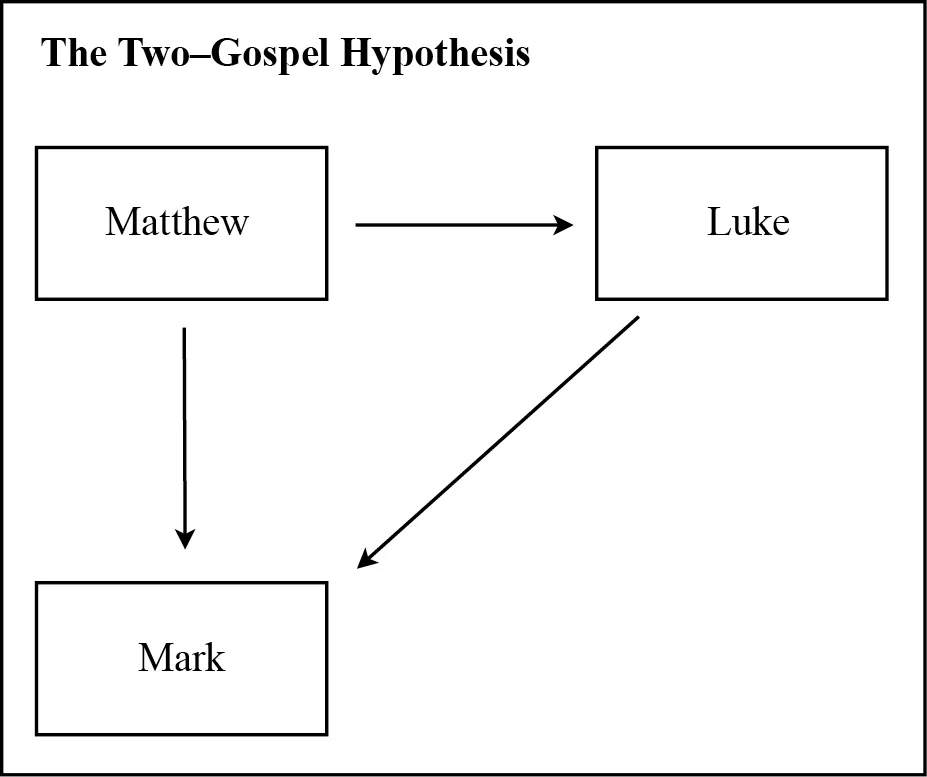

In 1776, J. J. Griesbach introduced and used the term “synoptic” (from σύνοψις, “seen together”) to refer to the three Gospels that have so much material in common, namely, Matthew, Mark, and Luke. It had long been recognized that the Gospel of John was radically different from the other three Gospels, and so it was placed into a category of its own. Griesbach challenged the Augustinian view of the order of the Gospels (i.e., Matthew, Mark, Luke) by proposing that Mark was the last Gospel to be written, itself being an abbreviation and conflation of Matthew and Luke (see figure 1).

Figure 1

Today, the “Griesbach Hypothesis,” more commonly referred to as the “Two-Gospel Hypothesis,” is not held by the majority of New Testament scholars on account of several arguments that they claim make the hypothesis untenable. One of the main criticisms is the question of why Mark would have wanted to write his Gospel in the first place, since it is an abbreviation, and since almost all of his Gospel is preserved in fuller forms in Matthew and Luke. It is also suggested that Mark, had he abbreviated Matthew and Luke, would not have wanted to omit some of Jesus’ most valued and well-known teachings. Despite these criticisms, some modern scholars have maintained the Two-Gospel Hypothesis, most notably William R. Farmer, whose work is largely responsible for the “revival” of the Two-Gospel hypothesis.

Griesbach’s hypothesis had a large following for several decades until a new hypothesis was put forward in the nineteenth century: Markan priority. A group of German and British scholars was responsible for leading the way, and it was not very long until Markan priority became the dominant view. This theory was designated the Two-Source (or Four-Source) or Oxford hypothesis, and the most classic presentation of this perspective was B. H. Streeter’s 1924 seminal work, The Four Gospels. The theory states that Mark was the first Gospel to be written, and that Matthew and Luke, writing independently of each other, used Mark as a source (see figure 2).

Figure 2

This would explain why there is so much material in common between the three Gospels (this material is referred to as the triple tradition). The theory also presupposes that Matthew and Luke used an additional source (non-extant today) made up of large portions of sayings material. This hypothetical source—hypothetical because it is lost to us today and must be reconstructed from the text of Matthew and Luke—was called Q, an abbreviation of Quelle, the German word for “source.” The Sayings Source Q would help explain ...