- 90 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

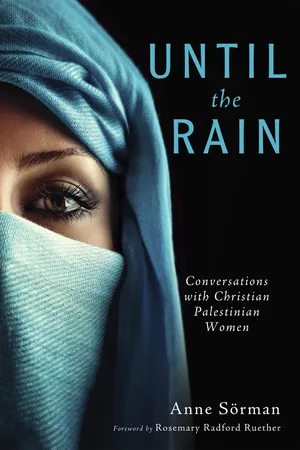

About this book

The Second Book of Samuel in the Hebrew Bible tells of a woman named Rizpah whose sons are sacrificed in the power struggle between the houses of Saul and David: Then Rizpah the daughter of Aiah took sackcloth, and spread it on a rock for herself, from the beginning of harvest until rain fell on them from the heavens; she did not allow the birds of the air to come on the bodies by day, or the wild animals by night. (2 Sam 21:10)Was Rizpah driven by the depths of despair? Or was she protesting in a woman's silent anger? The same kind of quiet defiance is playing itself out in contemporary Palestine. Is it grief or resistance--or the foundation of a new theology?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Until the Rain by Sörman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religion1

A Crack for the Light to Come In

It was late autumn 2009 when Mitri Raheb leaned forward and said: “I’ve been expecting you to come back and write about Palestinian theology.” I took his words as both an invitation and a call to action. He sent me a list of names and I spent the following winter formulating questions and sending e-mails.

I knew right off that I wanted to present Palestinian theology through the voices of women, the daily reality of life in the Occupied Territories as opposed to written documents and the words of clergy.

I returned to Palestine in summer 2011 for several hot and exhausting weeks.

Some of the women I had hoped to see were too busy. Others were taken aback: “Did Mitri really give you my name? That’s strange.” But many shared generously of their knowledge, time and thoughts. One meeting and set of questions led to another.

They came from different backgrounds, circumstances, educational backgrounds and religious affiliations. Jean Zaru is a Quaker and Marwa Nasser is a Lutheran, while Lucy Thalihej and Nadia Harb are Catholics. Yasmine Khoury is a member of the Syrian Orthodox Church and Nora Carmi belongs to the Armenian Apostolic Orthodox Church. Lucy and Marwa have degrees in theology, and several of the others have university training as well. Jean (the only Palestinian Christian woman who leads a religious community) and Nora have long been involved in ecumenical efforts. Natasha Al Zoghbi is a nun and Nadia is a social worker.

I met most of the women for the first time that summer. Nadia and Natasha, who are sisters, have been my friends for more than twenty years.

I started off with a few fairly general questions. How can you maintain your faith in the Christian gospel of love in violent and unjust times? How can a Palestinian Christian relate to the biblical stories about God’s chosen people? What is the foundation of contemporary Palestinian theology? Where is it heading?

Perhaps the main reason I decided to focus on women is that experience tells me that they are the pillars of daily life in Palestine. And they are the people among whom I feel most profoundly at home. Men’s voices had been heard all the way to Sweden. Now I wanted to explore the interplay between political, human, and existential issues from the perspective of women. I was eager to find out whether Palestinian theology changes, whether new doors and rooms open, when women articulate it.

Contextual theology arose in tandem with Marxist theory when Latin American clergy and theologians of the 1960s and 1970s found it necessary to articulate a creed that was relevant to poor farmers and laborers. The theology stressed the radical nature of the gospel, the notion that Christian salvation also embraced the here and now, that Jesus was the champion and advocate of the outcasts and underprivileged. A fundamental critique of power and the Church was often combined with an emphasis on freedom from poverty and oppression as opposed to salvation from personal suffering. Liberation theology emerged as the official term for this perspective, the roots of which lay in the popular struggle of the Latin American people. Contextual theology has become the umbrella concept for the interrelated theologies and points of view that derive their power and essence from a particular set of circumstances: the destinies and worldviews of Palestinian farmers, second generation immigrants in the suburbs of Europe, indigenous peoples, LGBT persons, people with disabilities, children, etc.

An Anglican priest by the name of Naim Ateek, who began to formulate a Palestinian theology of liberation in the early 1980s, eventually founded the Sabeel Ecumenical Liberation Theology Centre in East Jerusalem. As a theologian and pastor, he thought it necessary to relate to the complex conflict with Israel and to define a particular Palestinian Christian perspective. Proceeding from questions of justice and biblical interpretation, he critiqued the concepts of land, border, and kingdom in the Hebrew Bible. His focus is on the New Testament and Christ, who preaches a Kingdom of God without borders, setting the stage for a radical understanding of ownership, as well as national and geopolitical rights.

Ateek’s theology has clear pastoral themes, affecting his view of the Bible—how can a congregation living under military occupation find consolation in scriptural stories and prayers? Is the God who inhabits the Bible capable of acknowledging Palestinian suffering?

The second most prominent contemporary Palestinian theologian is German-educated Mitri Raheb of the Bethlehem Lutheran Church. In addition to preaching, he has published a number of books and articles. He founded the Diyar Consortium, an ecumenical community development project, in Bethlehem and has arranged a series of international theological conferences. As opposed to Ateek, Raheb speaks of contextual rather than liberation theology. His focus is on strengthening the Palestinian cultural and religious identity, seeking new paths beyond traditional Western theology. I see him as a pastor and teacher motivated by the desire to reclaim the entire Bible for Palestinian Christianity.

Fernando Segovia, Oberlin Graduate Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at the Vanderbilt University Divinity School, participated in a Bethlehem conference during summer 2011. He linked Palestinian theology to four different kinds of theory and practice:

1) Liberation theology, with roots in Latin American materialistic criticism of the Bible

2) Postcolonial theory and critique

3) Studies of minorities, race and ethnicity

4) Cultural studies, or the encounter between the history of religion and culture

What strikes me about Palestinian theology is that it arises from its unique propinquity to biblical stories and places. Bethlehem, the site of the manger in which Jesus was born, is located in the occupied West Bank. He appeared to his disciples by the sea of Tiberia in what is now Israel. He visited Simon the Leper—as well as Martha, Mary and Lazarus—in the village of Bethany, now cut off from Jerusalem by the Wall.

This traumatized and militarized area is where Jesus wandered, preached the gospel, was crucified and resurrected to eternal life. Palestinian theology is a response to the experience of expulsion, which began in 1948 when almost one million refugees were created, followed by exile, oppression, abandonment, and occupation. It also stems from a narrative with roots both in the soil and in historical events that vibrate with profound political and human resonance. Like the narratives of many downtrodden and dispossessed peoples, it is sustained by powerful emotions, homesickness, the need for a future, and a quest for affirmation.

I spoke with women, expecting to encounter hope and courage, to witness the gospel at work in the milieu from which it originated. It didn’t take long, however, for me to realize that I was off track. The walls were higher and human forbearance that much greater. Fear and oppression had left deeper scars than I was willing to see. There was a difference, if only in cadence or gesture, between word and meaning.

A crack appeared for the light to come in. And maybe that’s the only thing I can pass on.

2

Under the Almond Tree

There must be thousands of shawls in Jerusalem: white, pink, silver, silk, tulle, spangled, fringed, sequined and ribboned. Women toss them over their shoulders or knit them tightly around their heads, hiding both their temples and their necks. Many women match their shawls with their make-up and clip them to their hair. I enter a shop on one of East Jerusalem’s narrow streets and rummage through piles of shawls. They are sorted by color and type of material, and I finally settle on a silk one with long fringes. As I try it on, stroke it, hold it up to the light, I imagine the way that it will cover my head and shoulders when the sun is blazing.

A few hours later I find myself sitting in a Palestinian service taxi. All seven passengers are heading for Bethlehem. I’m in the front seat with my handbag in my lap. The city recedes behind us and the roads grow bumpier as we drive through a fading desert landscape. High up on a mountain crest with a dazzling view, the Israel Defense Forces have set up a roadblock in a little village. The line of cars grows longer by the minute. A man with an old-fashioned brass jug walks around and sells coffee in small white plastic cups. Before long a helmeted soldier with an automatic rifle on his hip ambles our way. He looks at everyone in the car, asks for my passport and examines it. I can feel my heart pounding.

“Are you in a hurry?” he smiles.

My fellow passengers sit there quietly, motionlessly, with their papers in their hands.

“Don’t look at me that way, Madame,” the solider says and fixes his gaze on me.

I suddenly remember stories about cars that had been shot into at checkpoints simply because somebody had annoyed a soldier. I think about Maysoun, who had to wait for hours even though she was already in labor. I loosen my new shawl.

When they finally let us through, the driver floors the accelerator and turns up the music on the radio. Dust wafts in through the open windows and mixes with the smell of smoldering brakes. One of the women in the back seat offers us nuts out of a little brown bag. I hear my phone chirp and think that it must be a text from Nadia wondering why I’m late, but it’s from the local Internet provider: Hi, Marhaba, smell the jasmine, taste the olives. Jawwal welcomes you to Palestine.

I get out by the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, cross the square and walk down the hill. The road follows the slope, passes a refugee camp that has almost merged with the town and turns towards the Separation Wall. The watchtower is right in front of me. Layer upon layer of slogans and graffiti cover the wall. A bright yellow taxi appears out of nowhere and Nadia steps out, walking in my direction with a big smile on her face, hair glistening and a handbag on her shoulder.

“How did you know that I would show up right this minute?” I burst out.

She just laughs.

We sit out on the balcony and dangle our legs over the edge.

“Whew,” Nadia sighs, “...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- 1. A Crack for the Light to Come In

- 2. Under the Almond Tree

- 3. God Has Called Me to Live

- 4. In the Light of God’s Love

- 5. A Household that Celebrates Life

- 6. Seeking and Service

- 7. At the Wall, Next to the Wall

- 8. God in the Belly

- 9. “The Occupation is a Sin”

- 10. Where My Heart Is

- 11. With Biblical Wrath

- 12. Until It Hurts

- 13. Women and Their Experience of God

- 14. To the Tune of Sorrow and Exhaustion

- 15. From Exodus to Liberation

- 16. Is Faith Possible?

- 17. Toward a Postmodern Palestinian Theology

- 18. Unexpected Rain

- 19. Like the Incense that Rises from the Mount of Olives

- 20. Friendship in a Time of Illness

- Bibliography