eBook - ePub

Forensic Scriptures

Critical Analysis of Scripture and What the Qur'an Reveals about the Bible

- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In Forensic Scriptures Brian Arthur Brown presents a long overdue Diagram of Sources of the Pentateuch from Hebrew Scriptures, a new perspective on authorship of the document known as Q in the Christian Scriptures, an acceptable entree into particular disciplines of scriptural criticism for Muslims, and an exciting new paradigm from Islam identifying the role women may have played in production of the Qur'an and the Bible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forensic Scriptures by Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religionpart 1

Opening the Hebrew Scriptures

1

Forensics

The word “forensic,” from the Latin forensis, is derived from forum, referring to the place in ancient Rome where the court of public opinion, as well as the legal courts, heard evidence. The term requires the translation of “forensics” as “before the forum” or “before the courts.” In our time, the most popular usage is perhaps when DNA evidence is brought forward. Medicine, engineering, and other scientific fields may contribute evidence to identify the body or to prove something to the jury or to the public. Ultimately the “grand jury” is the public who should feel themselves involved in the system of justice and the rule of law.

This is the case in the matter of what I have called scriptural DNA, “identifying the bodies of Scripture,” in which we present evidence of the Bible’s origins and purpose in the search for deeper understanding. I employ the forensic terminology in respect for the seriousness with which many in the Muslim community are taking the critical techniques of this science, and, for interest, I extend that terminology to the chapter headings as if scholarship itself and the scholars of Scripture were on trial.

The whole community of believers has always had a role in experiencing God’s revelation in the Holy Bible, preserving it and transmitting it in a way that made it live in each generation. This happened through the long processes of inspiration, reciting, writing, and editing, through selecting books for inclusion in the sacred collection of the community, and even through groups of monks mass-producing copies by hand. God’s spirit moved through the technology of human innovation when the Gutenberg printing press was invented to speed up the process. Its first product was the Bible. This led to even wider dissemination through the Bible Societies, and the demand grew for more meaningful translations, versions, and editions.

This exponential growth in demand led to the production of more translations and versions of the Bible during my lifetime than in all the years of history prior to my own birth and the birth of others of my generation. As the bestseller every year since Gutenberg, the Bible remains before the court of public opinion in our time, and we now have evidence of its origins that offer proof of its meaning and purpose.

Professors and students, rabbinical scholars and Sunday school teachers, all have roles to play with this “work in progress,” an understanding of the nature of the Bible that I hope to elucidate. But it is finally in the heart and mind of each believer that God speaks through the Holy Spirit as these words are read or heard, and God’s Word is given. The reader or hearer is as much a part of God’s work in progress as the original writers, whether priests of old in Jerusalem or women who were the writers among the “people of the house” in Muhammad’s time. Connecting the two is the task before us in this research. The diagrams depict the evidence in a way not unlike the graphic charts produced for famous trials like that of O. J. Simpson, which made certain aspects of evidence clear to the jury and even to the television audience. I hope to make things just that clear. I depend on the expert work of scriptural professionals, but for reasons given, it is equally important today to express these findings in street language for the readers who are the jury.

The chart depicting the sources of the Pentateuch is produced to investigate its origins and to illustrate its contents. It may equip those with less technical training than the professional scholar to understand and appreciate their own roles in this unfolding drama, much as a jury might consider itself part of the justice system that participates in the outcome of a trial. Every person, from writer to reader in the scriptural continuum, has an important God-given role to play.

Some may take these two charts of the opening books of the Old and New Testaments as the starting point in what may become a professional career in biblical scholarship. Others may take very seriously the challenge of producing a Qur’anic diagram based on the prototype that appears as a two-page spread in this publication. Most readers Jewish, Christian, and Muslim, may simply use these tools to become more comfortable and at home with the technical concepts of critical analysis of Scripture. This will hopefully undergird their faith, which may be already meaningful beyond any need of proof, but in a way which becomes especially delightful, even thrilling, with the benefit of a more complete understanding.

With the encouragement of my friend, Professor Reuven Firestone of the Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, I continue to make occasional use of the term “Old Testament” to describe the “Hebrew Scriptures,” the phrase deemed more politically correct in many circles. Professor Firestone frequently insists that the collection of Hebrew texts from Genesis to Malachi is also an Old Testament for modern Jews. Judaism as we know it, or “rabbinical Judaism” as it is sometimes called, is a new religion, separate from, and developed on the base of the Old Testament, making Jews, Christians, and Muslims all “supersessionist” in respect to the charge sometimes leveled against those believing that one religious movement supersedes another.

Rabbinical Judaism became the new religion of a majority of the Jewish people after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE by the Romans. For centuries before this, the Judaism that produced the Old Testament Scriptures had centered on religious practice and sacrifices at the temple in Jerusalem, as prescribed in detail by the God of Israel in the Tanakh (the name by which this “Old Testament” is best known today among Jews). Without the temple as a center of worship and religious life, the Jews were unable to honor the temple practices described in the Hebrew Scriptures. Once they were in “diaspora” around the world, the Jews evolved their religion into an entirely new format and organization. This happened between the second and sixth centuries of the Common Era, producing a religion as new as Christianity itself. So the term “Old Testament” continues in use, to some extent, in both religions, and also in Islam, signifying its foundational role.

The sources that came together to produce the Old Testament were diverse. They were all powerfully and intimately connected to this people’s recollections and experiences of their encounters with God. The people had a passion to tell that story, beginning with the divine encounter experienced by all humanity, represented by Adam and his family, and then their own communal and familial memories of the experiences of the family of Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar, followed by Moses and the slaves escaping to the desert in hopes of forming a new kind of country, and a variety of subsequent experiences in their quest to work out that destiny, including the Davidic monarchy, the division of the kingdom, the exile in Babylon and the return.

Summaries of that story abound, including my own attempt to tell it through the eyes of Jews, Christians, and Muslims, or through “Abraham’s dysfunctional family” in Noah’s Other Son: Bridging the Gap Between the Bible and the Qur’an. The great story of the Bible and its people is crystallized in a kingdom-building dream by David for Jews, in personal and corporate redemption in Jesus Christ for Christians, and in God’s final revelation in the Qur’an given to Muhammad for Muslims.

There will be no attempt to retell that story here, but rather to set forth over a hundred years of scholarship concerning the Old Testament compendium of stories revered by all branches of this family: Jewish, Christian, and Muslim. In particular, this is done through a colorful diagram showing how a welter of sources was skillfully edited together into the Bible, the bestseller of all time. It is a foundational document of three religions and of Western culture, and a cornerstone of the world civilization that is emerging in the twenty-first century; therefore it deserves continued and growing attention.

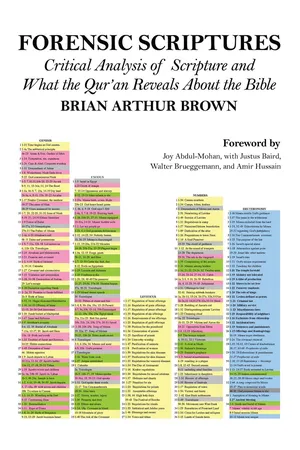

Modeled in many respects on the similar diagram depicting the opening chapters of the New Testament that has been helpful to Christians for over seventy years now, my Old Testament diagram appears on the cover. The New Testament diagram by Allan Barr is included by permission on the back cover. A prototype of a “Diagram of the Revelations of Allah in the Holy Qur’an” occupies a similar place, with a full prototype appearing as a two-page spread near the conclusion of this publication.

Allan Barr chose white, pink, yellow, and blue as all the best colors for printing such a diagram representing Mathew, Mark, Luke, and Q, with a tiny note in green for a couple half verses of Mark omitted by the others. I have selected pink, green, blue, and yellow as effective and dramatically attractive in representing the J, E, D, and P sources of the Pentateuch, as explained in the introduction above and in the text that follows. In my Old Testament diagram, gray denotes minor editorial touches by the redactor who edited the whole compendium in its final form and as we have it in our Bibles.

There are many written commentaries on the Four Document Hypo-thesis (or simply the Documentary Hypothesis) and hundreds of variations, major and minor, in assigning verses to each of these sources. I do not attempt to adjudicate between the scholars who have made undoubted advances on the original, and I essentially limit myself to the delineations made by Julius Wellhausen in 1884, based in significant part on the work of his mentor, K. H. Graff in 1866. Mistakes there may be, and improvements are always welcome in this field of study, but it is the Graff-Wellhausen version of the Documentary Hypothesis that was the watershed in the development and acceptance of critical techniques, equipping students and scholars with the tools to understand and go further.

So in the diagram, I basically adhere to the original Graff-Wellhausen assignments of authorship, as delineated by the color code, and as summarized in a table by Stanley B. Frost in 1960. There are some exceptions when both The Interpreter’s Bible and The Anchor Bible agree with the exceptions, and significant departures only where Richard Elliott Friedman convincingly overrules the other two in his turn-of-this-century masterworks on the subject, Who Wrote the Bible? (1997) and The Bible with Sources Revealed (2003), adopted with his acquiescence.

In this investigation there may be a tendency to sometimes lump Jews and Christians together with respect to critical techniques that they developed, not always jointly but certainly in tandem with each other. Jews and Christians are eager to share these techniques with Islamic scholars who have already signaled their interest. Jews and Christians are also increasingly intrigued by the traditional scholarship of Islam and eager to gain insights into the Qur’an for a range of reasons: to gain new information from this ancient lore about the Sitz im Leben of their own scriptural heritage, to experience spiritual growth inspired by a related scriptural tradition, and to improve familial relations within the still-dysfunctional family of Abraham, Sarah, and Hagar.

From the Qur’an and the Hadith we learn about Mary’s parents and her priestly vocation under the sponsorship of her uncle, Zechariah; we learn details about the Bible’s mysterious Sabeans; we learn of Noah’s fourth son, Canaan; we learn the names of women in the Bible like Pharaoh’s wife/daughter, Asiya, who adopted Moses; we learn of Potiphar’s wife, Zulaika, who entrapped Joseph; and we learn of Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba. From Islamic Scriptures we obtain a view of Gnostic writings and of material from the Gospel of Thomas that is similar to a vogue in both current secular literature and the media. There are even Islamic images reflecting the Gnostic and other hetrodox views of the Christian Messiah.

Possibly the most exciting aspect of Qur’anic study with the aid of critical techniques is a growing appreciation of the Qur’an as a template of scriptural compilation. It is an accessible model of scriptural formation from the last major culture to spring from the ancient Middle East, indeed from the same Abrahamic family as the Bible, and one in which reliable information about scriptural...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Foreword

- Prologue

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part One: Opening the Hebrew Scriptures

- Chapter 1: Forensics

- Chapter 2: Identity Theft?

- Chapter 3: Interrogation

- Chapter 4: Prime Suspect

- Chapter 5: Lineup

- Chapter 6: Arraignment

- Chapter 7: Cross-Examination

- Chapter 8: Objection!

- Part Two: Opening the Christian Scriptures

- Chapter 9: Discovery

- Chapter 10: Documentation

- Chapter 11: Corroboration

- Chapter 12: Fingerprints

- Chapter 13: Accomplices

- Chapter 14: Confession

- Part Three: Opening the Muslim Scriptures

- Chapter 15: Custody

- Chapter 16: Handwriting

- Chapter 17: Reasonable Doubt

- Chapter 18: Testimony

- Chapter 19: Summation

- Chapter 20: Sequestered

- Chapter 21: Conviction

- Chapter 22: Appeal

- Epilogue

- Appendix

- Bibliography