- 142 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

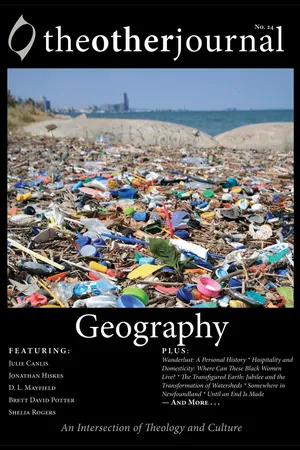

The Other Journal: Geography

About this book

FEATURING: Julie Canlis, Jonathan Hiskes, D. L. Mayfield, Brett David Potter, Shelia RogersPLUS:Wanderlust: A Personal HistoryHospitality and Domesticity: Where Can These Black Women Live?The Transfigured Earth: Jubilee and the Transformation of WatershedsSomewhere in NewfoundlandUntil an End Is Made--AND MORE...

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Other Journal: Geography by Other Journal in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Religion1

Lukewarm Coffee at a Blue Desk in Michigan

Words curdle. Words evaporate.

Words reconstitute in the scent of strong coffee,

in the kicked-up odor of wet, decaying leaves

present even in summer outside these city walls.

Our words were never

our

words.

The hand

can take up a pen or a brush

and create symbols: flesh

pulling meaning from nothing.

And how full that nothing is

with the dust motes in the church where you painted,

with the light of guttering votives

circling the Virgin’s skirt.

Full with silent prayers and the cold breath

of cobblestones. I often wondered

where you walked: satchel slung over shoulder,

shirt scrunched down to the skin of you,

the little current of air you generated—if it were

visible—a deep blue-green.

The eyes of my heart would follow you

up hills and down,

through the cool

shadows of grocery, garden, and nave,

through the sun’s stream beamed back

from walls, beneficent.

I rested my forehead

on your train window to Rome.

I followed you to the seashore

where you grew strong on wind and light.

I followed you not knowing

where you lived till I left for good.

To think my fingers could have touched that door.

To think my palm could have pressed the cool metal, turned;

that I could have entered and known.

My hands kept busy with bread

and cup, with glass and guidebook,

each day cradled

by the guttural beauty of the cool air at night.

(For the night had an imperceptible sound—

a dark, creaturely groaning and a

lilt soft as wings in cypress trees—

which unfurled

something like waking in the womb.)

2

Wanderlust: A Personal History

Who doesn’t know what I’m talking about?

Who’s never left home, who’s never struck out?

—Dixie Chicks

I am sixteen, sitting in Bible class at my small private high school. The teacher thinks—at least, I hope she thinks—that I’m following along in the book. In reality, I’m a rebel. I’ve nestled a paperback behind the cover of our text. While she lectures, I’m traveling across America with John Steinbeck and his dog Charley. I’m dreaming about leaving.

I have a happy, easy, middle-class existence in a charming southern city. There’s nothing I need to escape. My problems are simply the standard teenage woes: not fitting in, feeling alone, flirting with the isms that begin with solips and existential.

Despite all this, when I’m assigned to write a paper envisioning the next ten years of my life, I—student council president, editor of the yearbook, National Merit Scholar—I dream about becoming a truck driver.

See, at twilight in Arkansas, weekend nights when I decide to skip the parties because I just can’t bear them anymore, I go driving. Out highway 10, before it was developed, you could drive at sunset and after just five minutes you’d be in the country, old wild oaks, hickory and pine trees hemming you in, their leaves turning lacy black against the dusky sky. You could roll down the windows in April, and the air would be thick with humidity, the temperature of your baby brother’s bathwater, fragrant with magnolias. You could drive until the stars came out and never see a soul. You could pull over and lie on the hood of the gray car nearly as old as you are and listen to the cicadas. You could wax poetic in your journal about the light from stars that had died long ago and never once have to answer any of those questions they’d be asking at the party, questions about the weather or college or prom or, worst of all, what God had been teaching you lately (these were Christian parties, after all).

If I were a truck driver, I think, or if I were John Steinbeck—if I could refurbish a Volkswagen van and crisscross the country, highway-69ing it on my own, then maybe I could be free.

Take to the highway,

Won’t you lend me your name?

—James Taylor

I’m in college and I’ve begun to believe that this is just something in our blood, all us European-Americans. We were born of those who chose to leave. We’re made of sturdy immigrant and pioneer stock. We have a manifest destiny and are nothing without a new frontier to explore. And—

This isn’t an original idea. The historian Frederick Jackson Turner wrote in 1893 that “To the frontier the American intellect owes its striking characteristics.”1 Turner argued that because the frontier forced American institutions to continually adapt and re-create themselves as they expanded with it, they underwent a “continual beginning over again.” That process, explained Turner, created uniquely American people and institutions. His theory of American development was wildly popular with historians and politicians alike. Woodrow Wilson published several articles in popular journals in which he called the frontier “the central and determining fact of our national history.” John F. Kennedy regularly used frontier rhetoric to appeal to and challenge Americans, reinventing manifest destiny with an eye toward space.

Later historians complicated Turner’s ideas. George Pierson argued that it wasn’t the frontier but the related M-factor of movement, migration, and mobility that defined the American people.2 Texas historian Walter Prescott Webb argued that Turner’s thesis did not apply uniquely to Americans; many nations had experienced national frontiers. However, Webb wrote, the closing of the frontier in America uniquely shaped the American psyche. Since then, Americans have been searching for new frontiers to conquer:

The business man sees a new frontier in the customers he has not yet reached; the missionary sees a religious frontier among the souls he has not yet saved; the social worker sees a human frontier among the suffering people whose woes he has not yet alleviated; the educator of a sort sees the ignorance he is trying to dispel as a frontier to be taken; and the scientists permit us to believe that they are uncovering the real thing in a scientific frontier.3

Cultural studies also speak to the power of the frontier myth: “Myths are stories,” Richard Slotkin says, “drawn from a society’s history that have acquired through persistent usage the power of symbolizing that society’s ideology and of dramatizing its moral conscience—with all the complexities and contradictions that consciousness may contain.”4 These stories are by nature vague, and their historical veracity is unimportant to their functional ability. Rather than appealing to reason, they invoke memory and nostalgia through metaphoric representations and our intuitive recognition.

Ultimately, the frontier myth reconciles conflicting desires to fulfill both individual and communal needs, to pull up roots and explore new horizons and at the same time to attend to the needs of the community. The hero of the frontier myth—think Daniel Boone, Natty Bumppo, Davy Crockett, and Buffalo Bill; think any cowboy in any Western movie you’ve ever seen—functions symbolically as an instrument to reconcile those desires. He can ride into town, save the day for a community, and then leave to continue taming the West on his own. Therefore, he fulfills a responsibility to community without actually committing to community.

And so historians call us a nation of restless wanderers with an unshakeable migratory compulsion, and in this myth of the rugged white male who can’t settle down, I recognize myself, a sixteen-year-old girl sitting in Bible class dreaming of highways. I see an excuse for my wanderlust, a reason to travel to every new place, to experience the whole world without feeling guilty about what—or whom—I’ve left behind.

One more song about movin’ along the highway.

I can’t say much of anything that’s new.

—Carole King

I’m a lot like Jack Kerouac, you know: I’m almost twenty-one and I’m backpacking across Europe, sometimes with friends, sometimes on my own, restlessly, aimlessly traveling like Kerouac did in the epic road trip he immortalized in On the Road. I wake up on gently rocking trains and open the windows, breathing the fresh green scent of a new country, clutching a paper cup of steaming strong coffee and a hard roll. I put in my earbuds and listen to music no one else can hear. I watch the sunset on a hostel balcony with strangers, swapping stories like salty fisherman. Where did you come from, where are you going? Drinking cold beer, we share our most fantastical tales—

“I had a roommate who got drunk and climbed the high steeples of the Megyeri bridge over the Danube.”

“The communal goulash at the hostel in Budapest was served with hashish.”

“We went skinny dipping off the Isle of Capri and did yoga in the Roman ruins.”

We never see each other again.

This is the kind of community I love, forged with the transient...

Table of contents

- CoverImage

- 01_theotherjournalGEOGRAPHY_fm

- 02_theotherjournalGEOGRAPHY_chapters

- 03_theotherjournalGEOGRAPHY_backmatter