![]()

1

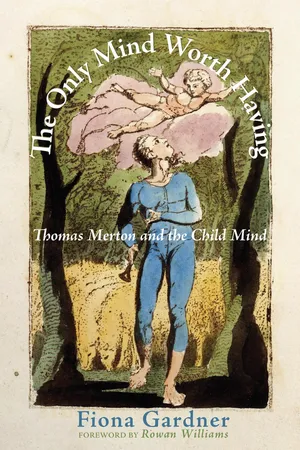

, to Thomas Merton, and to Ideas about the Spirit of the Child

In three of the four gospels Jesus commands those wanting to follow him to change, to receive his teachings and experience discipleship as a young child:

What did Jesus mean by his statement to become like children—or the “little children” of Mark and Luke? What does it really mean to become as a small child when you are an adult and now in this secular twenty-first century? Is it only possible to become as a small child and so receive the kingdom of heaven when you are weak, ill, or vulnerable or could we choose to search for it? Is it possible to find a spiritual practice that encourages this without becoming sentimental and mawkish, or regressive and pathological in some way? How can this be understood as part of our contemporary spirituality? Is it just about being immature or is it in some mysterious and paradoxical way the path towards spiritual maturity?

Although the gospel words are regularly read and widely known, certainly amongst Christians, the command is so counter-cultural and so personally challenging that perhaps there is often only a superficial sense of what it might really mean. Most grown-ups feel that they have left childhood far behind and for anyone who has struggled to escape from the long shadow that a difficult childhood can cast over adult life anything that might seem like a form of regression is anticipated as a potential danger zone. Yet all grown-ups, including theologians, carry within them both the child they were and memories of childhood; these can be happy or sad or, as for most people, a bit of a mixture.

Alongside this there can be often also a feeling of shame when childish thoughts or feelings belonging to the past suddenly re-emerge. This may be especially so around belief, or worship and the personal relationship with God. Perhaps it feels we have to be very grown up and reasonable and rational with God, so what is judged as childish emotions have to be suppressed or disowned. However, perhaps when particularly weak and susceptible, the illusion of adulthood seems to melt away and we are left turning to God stripped of our usual defences. In such moments we can feel quite small and vulnerable and this is often an uncomfortable and an unwanted feeling.

“Unless you change and become like children”—Jesus’ command in Matthew is quite clearly about a process of disruption and development. None of us like to change as it means breaking up what seems to be familiar and predictable—even if one is stuck in a place that is not particularly helpful or comfortable. There is always a resistance to interrupting what we usually do and who we usually see ourselves as; there is often apprehension of what a change might lead to. “Become” means to begin to be, to come into existence, to change and to grow, to develop into. It is a word that describes movement and a process. It is about potential, it seems to be about moving forward, but in the context of becoming a small child it is also paradoxical. It then seems to be a backward step and a contradiction to become something that we have already once been.

The poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote: “The child who dwells inside us trusts that there are wise men somewhere who know the truth,” and it is here that Thomas Merton can be of real help. The Trappist monk and writer Thomas Merton (1915–1968) has been an inspiration and influence to many. The centenary of his birth—he was born 31 January 1915—has given another opportunity to reconsider his legacy and welcome his often unconventional and penetrating insights. He was born in France and spent part of his youth in England before settling in the United States. He became a monk based in the Abbey of Gethsemani, in Kentucky, North America for twenty-seven years, and was a prolific writer and a poet. He wrote over seventy books including volumes of journals, poetry, and spiritual writing, as well as about 250 essays on all sorts of issues including peace, social justice, and inter-religious dialogue. He also wrote at a conservative estimate at least 10,000 letters to around 2,100 correspondents. The probable number is much higher. Correspondents included many who sought spiritual advice and guidance from someone whom they recognized as having struggled to make sense of life and to find God.

Thomas Merton has been called a theologian of experience as he wrote about his own life experiences, his environment, and the world in all its complexities. In that sense he is an experience-near as distinct from an experience-distant writer and thinker. He thought and wrote about what he personally knew and about what had affected him. He carried as an adult the child that he once was and he wrote about his childhood in an early autobiography. This account will be explored in a later chapter. He also wrote about something that he called the child mind. This book is in part an exploration of what he may have meant by that term. In his writings about his life and his spiritual insights he sometimes used the term “child mind”—as in the quote at the start of this book—to describe a way of being with God. Indeed he thought that it was the real way to be with God—it was the only mind worth having.

Both spiritual and psychological insights can be helpful here, and it is possible to use ideas from both as a way to understand what Merton might have meant and beyond that to illuminate that most enigmatic of commands from Jesus: “Unless you change and become like children.” It is a command and a direct piece of guidance from Jesus and yet also a concept that becomes cluttered, confused, and resisted by our own experiences of childhood, our ambivalent experiences around children, and the societal views of what and how children are or even should be.

The command is enriching and surprising, and as my understanding of what it might mean has deepened so I appreciate that it is less about the clinging and neediness of an actual infant—though dependency plays a part; nor is it only about accepting a sense of humility, loss of status, and powerlessness—though that is another aspect. It is not about returning or regressing in a pathological way to one’s own past, though some elements may be relevant. It is not about sentimentality or a stereotyped view of innocence, and it is not about pretending to be simple or simple-minded. It is not about denying or decrying adulthood. What it is about is the adult mind uncovering, discovering, recognizing, and then integrating the eternal child—the Christ child—who is present and within the psyche of everyone.

The central suggestion in this book is that as he matured spiritually Thomas Merton came to embody the spirit of the child and that he is the ideal spiritual guide who can help to illuminate this process and the command—“Unless you become . . .” There is no specific work in which Merton wrote on this—rather he lived it, and it is the becoming and the living of it that shines through in his writings and that can provide inspiration. It is worth noting that if you look in the index of any of the published volumes of his journal, there is only one reference to the word “child” or “children.” This reference though is absolutely central to Merton’s life and work; this is about what it might mean to become a child of God.

Thomas Merton’s spiritual journey, from the time before he entered the monastery and including his many years there, was a journey to become the person that God intended him to be. He wrote about recovering the promise of childhood spirituality as he described what happened to his sense of self during contemplative prayer. He wrote about a way of being alive, and he thought that as adults this state of mind, when it happened, brought us spiritual wisdom and led to maturity. He understood this as paradox, an apparent contradiction but a contradiction that was worth exploring both from a psychological and spiritual perspective.

For Merton the spirit of the child found in the child mind was above all about a lack of self-consciousness; for him this was a process of letting go of the self or the disguise that we present to the world. He called this the false self, an idea discussed later in the book. It involves a process of renewal, almost a re-emergence of another more genuine part of our selves, which he called the true self. In Merton’s experience the child mind also involved a journey towards a simplicity, trust, and openness in the adult relationship with God. Although as an adult Merton was clearly an independent person he was always open to God and Merton’s ongoing cycle of conversion and renewal inevitably brought increased closeness to God—what I later refer to as a state of being-in-dependence with God. Thomas Merton understood that this was a state of being-in-dependence with Being. It was not about a sentimental nostalgia for an idealized time in his childhood, nor about psychological collapse into pretend babyhood. Instead it was about recapturing qualities of attentiveness and receptivity. It was about being awake to connections and the life force within all creation. It was therefore about a change of consciousness, or rather a return as an adult to an earlier state of consciousness that is actually known to everyone from infancy. Thomas Merton thought that this restoration essentially came about through contemplation.

As in contemplation, this developing consciousness is about being totally present to the moment and is something that each of us already has experienced when very small. It involves times when thinking is minimized, and when the focus on God excludes some of our usual self-consciousness. It is in other words a state where, even if only for a second, we are preoccupied with and absorbed in God. Many of the other writers, whose thinking and experiences are also included in this book, would agree with Merton that this can be approached through the stilling of the mind in contemplative prayer. For contemplation brings with it a change of consciousness. Gradually in the silence old preconceptions and ways of being can begin to loosen and a different way of relating both to God and to ourselves becomes apparent. This in turn affects how we are with others and how we are towards creation and the environment.

Contemplation can, over time, bring us to an appreciation that all is connected, and all is held in creation by the merciful God. Merton wrote extensively about contemplation and believed that it is the way in which each person can let go of the false self—the mask or disguise that we carry—and come to know the true self. In this book one of the suggestions is that this true self, present in each of us, is the child mind. It is the spirit of the child, where we can recover the promise of a childhood spirituality we have all once known, a spirituality that can be returned to without dismissing what we have become.

It is suggested that within each person is the early mysticism known to every small child—a state of heightened experience and amazement. This amazement is about wonder and can also include fear. It can lead to a remarkable and seemingly firm certainty of oneness and connection within the world. This childhood mysticism becomes buried in the journey to adulthood and the reasons for this are explored in the book. Yet the feelings linger somewhere within the psyche and it is seen as “something that shines into the childhood of all and in which no one has yet been: homeland.”

Edward Bouverie Pusey, the nineteenth-century Tractarian, thought that the words of a child spoke greater truth than they (the child) knew; they had a glimmering of the truth though they could not grasp it.

As adults there can be such moments of re-experiencing deep connections where we forget our everyday self, and where we return to an earlier simplicity. It could be seen that we join with the presence of the eternal child deep within each one of us. It can be a moment of grace through which each can be renewed, a moment of rebirth. At that moment we reconnect with the true self and the experience of God. Merton, in a much quoted passage, wrote about contemplation as the experience of God’s life and presence within us “as the transcendent source of our own subjectivity.” In other words we lose the separation between ourselves and Divinity—the connection that is obscured as we grow older.

It is ironical that the qualities belonging to childhood spirituality ca...