- 132 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

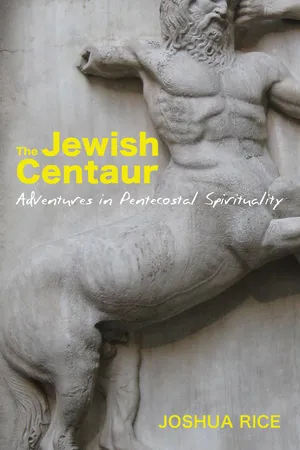

About this book

In this spiritual memoir, Joshua Rice explores his Pentecostal history in search of a tangible theology to fall in love with. From the revivalist urges of the Deep South to mainline Protestant halls of learning, this quest for God leads to and through personal stories of encounter, of dissonance, of doubt, and of faith. Since the Azusa Street Revival launched the global Pentecostal movement a century ago, the chase has been on to figure out what God is up to. The Jewish Centaur follows the trail, seeking to discover.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Jewish Centaur by Joshua Rice in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Sozialwissenschaftliche Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Jewish Centaur

You must learn to look at the world twice if you wish to see all there is to see.

—Jamake Highwater

It was my second semester teaching college freshmen as an adjunct professor at our Pentecostal denomination’s flagship university. The class, an introduction to the New Testament, is a core requirement for all students. One of my classroom routines is to try to understand the theological background of the students, not only for my own sake but also to guide them toward understanding the impact that context, especially social location, has on reading the New Testament. I read the Bible as a middle-class white male. I can’t help it. Helping students become a bit more aware of their own lenses is an important part of a college level Bible class.

I have now taught for four semesters, and the theological breakdown of the students has been the same each time. The vast majority of them have been steeped in church from birth. This being the South, usually half of them are Baptists and the other half Pentecostals. Not many of them have read the Bible much, which is a new development in both movements, but they know the stories. These are church kids. They cut their teeth on varnished oak pews.

The fact that they are church kids actually makes the class difficult to teach. Growing up in the Southern church is a totalitarian experience. These college students have been bequeathed a complete worldview that accounts for everything: how creation was created, why we exist, what we are here to do, and how it will all wrap up one day. Church isn’t one component of life. Church is the bank of raw thought material that equals life. Church equals life equals reality. Some of these kids have never been to Atlanta, let alone Paris. Peeling back the onion of their reality to get at the lenses and biases they bring to the task of biblical interpretation is no easy task. They have never considered life outside the onion. This is not a bad thing, depending on the onion.

I always begin the class by asking the students to reflect on elements in American culture that call us Christians to know something about the origins, composition, and contents of the New Testament. This is a less threatening way to move them toward considering the complexities involved in interpreting the Bible. But even this got nowhere with the students in my second semester. They have just never thought about it. If your subconscious soup has been formed by the biblical narrative, the world easily conforms to your unquestioned worldview. The church is the only culture they have known, so the thought of engaging another arena of culture is foreign. It’s not that they aren’t aware that nonchurch culture exists; it just gets folded into the meaning of the church in the first place. We are right and anyone else is wrong. End of discussion.

This dynamic is tricky to manage in the initial sessions of the class when we walk through the composition of the gospels. Most Christians are trained to read the Bible like the Koran or the Book of Mormon, as if it floated down from heaven on golden plates, chiseled by God like the Ten Commandments. In fact, our Bible sets Christians apart from adherents of other faiths, not only in its competing truth claims but also in the complexity of its composition. It is very careful surgery to help these students understand that what they often call “the worda God” was written by particular authors, in particular places and times, to address the particular needs of their audiences. Jesus was not a phantom floating six inches off the ground. He was a man with body odor and real theological opinions, in conversation with other Jewish teachers with body odor and real theological opinions. It may sound basic, but this is all new to the college freshmen I teach—or try to.

The crowning moment of my second semester of teaching occurred when we reached the session on the Gospel of Mark. Mark is the first narrative about the life of Jesus ever written down, so there is a lot to cover. One of the first and foremost questions that I address is the identity of Mark’s audience. What we can know about this is key to determining Mark’s goals and purpose. Who is Mark written to, and how do we know?

Allow me to re-create the scene:

“Determining the audience of Mark starts with determining who the first Christians were. We know that Jesus and his early followers were Jewish, so we might expect that the earliest Gospel was written for Jews. However, this is not the case. In fact, there are clear indicators in the text of Mark that the Gospel has been crafted for a Gentile Roman audience.”

After pausing to ensure the students know the difference between a Jew and a Gentile, I build on the foundation I have laid, feeling confident.

“We could look at many examples in the stories of Mark that suggest this Gentile Roman audience, but the greatest example is actually the climax of the entire story. It is an alarm bell, alerting us to Mark’s audience. Go ahead and turn to the end of the story, Mark 15, and we will have a look at the climax of Mark’s story arc. This is, of course, the chapter that narrates Jesus’s crucifixion, the moment in the early Jesus movement when it looked like the movement was over. However, when it looks as if the story is over, suddenly the least likely voice takes center stage in the narrative.”

And when the centurion, who stood there in front of Jesus, saw how he died, he said, “Surely this man was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39)

I’m getting something in between nods and blank stares from my students. This is all so new to them. I double down on the significance of this verse.

“Even before the resurrection, this moment in Mark 15 represents the culmination of Mark’s entire Gospel. Mark lays out the trajectory of the story in the first sentence of the entire book, announcing, ‘The beginning of the gospel about Jesus . . . the Son of God.’ As a master storyteller, however, Mark makes it difficult to track the evidence for this thesis. No one seems to discern the identity of Jesus in Mark’s gospel, whether friend or foe. When Peter finally hits the nail on the head in his monumental confession of Mark 8:29, ‘You are the Christ,’ Jesus doesn’t answer a thing, except to tell them all to shut up about it. In the next scene, Jesus calls the guy who just called him the Christ, the devil himself!”

Are they with me? I thought so a moment ago, but now it is hard to tell. Fewer nods. Blanker stares.

“It is only when the centurion confesses to the corpses on the cross, ‘Surely this man was the Son of God!’ that the story comes full circle. The proclamation rings out, with no one now to demand silence. Mark has proven his point. The grand reveal is that it is not the disciples, the Pharisees, or the crowds who figure out the riddle of Jesus’s identity. It is the centurion who supervised his crucifixion! Isn’t that astounding?!”

At this point in the lecture, I’m breaking for the end zone like a running back who’s just stiff-armed the safety.

“So now that you know all this, why do we then assume that Mark is writing to a Roman audience?”

Crickets.

I regroup, trying to remain positive.

“We know Mark is writing to a Gentile audience because of the centurion’s proclamation.”

It feels like playing peekaboo with a group of children. I’m not leading them anymore. I’m trying to give them the answer to the question.

Then I unforgivably break the cardinal law of teaching. I publicly ask a question that I thought was rhetorical to students who haven’t the foggiest notion what I’m talking about.

“The centurion’s proclamation is so significant because of his ethnicity. Because is the centurion Roman or Jewish?”

The lone senior in the class (an education major) confidently responds. “Jewish,” she announces to the class with great emphasis, as if pronouncing the winning word in a spelling bee.

My composure is withering as I try neither to embarrass her nor to capitulate to the fact that this lecture is a disaster.

“Well, no, he’s actually a Gentile, because . . . as I’ve been saying . . . he represents the crescendo of Mark’s narrative that is crafted for a Gentile audience. So we know that he is a Gentile because he is a centurion.”

Then, like a gambler getting destroyed by the house, trying to make up lost ground, I go all in.

“What would you compare a centurion to in our day? Does anyone know what a centurion is?”

I throw out some options: police officer, military personnel. Nothing doing. Finally, a voice speaks clearly from the middle of the classroom. “Oh, I know. It’s a half-man, half-horse.”

A centaur. A Jewish centaur. And that student was not joking in the least.

I have never taken drugs, but the feeling that wafted over me when that student spoke those fateful words must approximate the experience. There was a rush of panic at the realization that I am a complete failure at my chosen vocation and should never again be allowed to professionally interact with another college student,...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Jewish Centaur

- Chapter 2: The Holy Spirit

- Chapter 3: Holiness

- Chapter 4: Authority

- Chapter 5: Culture

- Chapter 6: Preaching

- Chapter 7: Liturgy

- Chapter 8: Revival

- Chapter 9: Tongues

- Chapter 10: Salvation

- Chapter 11: The Bible

- Chapter 12: Evangelism

- Chapter 13: Relevance

- Chapter 14: Mystery

- Chapter 15: Theology

- Chapter 16: The End Times

- Chapter 17: Community

- Bibliography