![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

There is great interest in visual culture within academia these days. Nicholas Mirzoeff writes, “Visual culture is now an increasingly important meeting place for critics, historians, and practitioners in all visual media who are impatient with the tired nostrums of their ‘home’ discipline or medium.” It is hoped that this work might not only be of interest to theologians and students of architecture and the built environment, but to historians and art historians interested in how to better access the past through learning to see the way early modern citizens might have seen; and to understand how conceptions of space and religion manifested themselves in buildings that still survive today. Although the Neoclassical style can now be seen in Catholic churches, it was an innovation largely brought about by Protestant architects. It is only in understanding the language and visual quality of space that we can truly understand the resistance offered against competing religious ideologies in their creation of the built environment.

Conflicting Aesthetics

This work proposes that the Protestant architecture in francophone territories of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was laden with theological meaning. This will be explored by treating three contrasting examples: St. Pierre in Geneva, a Calvinist church taken over from Catholics, St. Gervais-St. Protais in Paris, a Catholic church finished by a Protestant architect, and finally a purpose-built Reformed church designed and built by that same architect. The time period will be approximately mid sixteenth-century Geneva, to be compared with the first two decades of the seventeenth century in France. The rationale for this period is that it encompasses the time of the first conscientious scrutiny of space fit for Protestant worship and the time of maturation of specifically Protestant church architecture. Together, the structures under consideration begin to suggest a Reformed approach to sacred architecture. Further, we will discern two distinct ways of seeing, one Catholic and one Protestant. Religious traditions incline to certain ways of perceiving what is good, true, and beautiful. This reality has much to do with architectural space, its style determined by how one sees reality. Finally, we will suggest that Protestant habits of design helped set the stage for the development of the Neoclassical style in France.

Yet even in the churches who found their identity in the exposition of Scripture, the habits of medieval Catholicism died hard. The 1659 Registres du Conseil of Geneva relate that concerned pastors and elders witnessed church members kneeling before a statue at the tomb of the Duke of Rohan in the Cathedral of St. Pierre, praying before the Huguenot leader’s memorial. The statues of Catholic saints had been excised and the Mass abolished for over a century, and yet old habits of devotion were not so easy to eradicate. Similar stories of the resiliency of “idolatry” emerge from continental and British settings alike. Especially in isolated country towns, “the results of the Reformed churches’ endeavors to root out folk customs and magical practices, and to construct in their stead a new religious culture, were mixed, particularly when pastors and elders challenged popular traditions and time-honored social exchanges.” In the midst of monumental changes and reform, old customs sometimes still controlled popular practice.

Stories of enduring religious customs, as when women genuflected before a whitewashed church wall that covered a sacred image, illustrate the stubbornness of folk beliefs and the difficulty of reform, on one hand, and the lingering memory of sacred presence, on the other. Eliminating these practices and instilling new forms of piety was difficult work. These accounts also raise some interesting questions: do parishioners retain some dim recollection over generations of images that helped them cope with adversity or prepare for the experience of worship? Do they recall more explicitly what initially elicited their devotion? Is the act of praying to the image of a Huguenot hero meaningless, or worse? Do certain elements within a church building generate an impression of holiness? More broadly, what does Reformed worship space express, and how does it do it? How is space provided for worship intended to function, and how do cultural artifacts enhance it (or conversely, perhaps compromise its purity?) Or is Reformed architecture itself deficient in that it is incapable of meeting a need for sacred space in a horizontal community of peers, and in a vertical community through history? These are questions to which we will turn.

The medieval Catholic imagination, or manner of attributing meaning to what is seen, focused on images external to itself in which it found transcendence. However, the Protestant critique of this manner of seeing argued that the imagination focused on an image can only comprehend its interpretation of the image, whose reality takes form in the imagination. David Morgan, in The Sacred Gaze: Religious Visual Culture in Theory and Practice describes (sympathetically) how images work. He points out, “In every case, viewers experience an absorption in an image. They cultivate a variety of visual practices that engage them in this absorption . . . [this can be] contemplative, bringing the mind into deeper experience of itself . . . .” But this was the very problem for Protestants. This work will argue that for them, this approach to the divine encompassed both the nothingness and the power of images, through which one perceived oneself and projected that image upon God. When faith orients itself toward objects, it is claimed, it becomes indistinguishable from one’s idea of faith or from an experience of the religious imagination. The imagination that only contemplates itself reminds us of what Barth called “pre-judgment” toward Scripture, which he says “is not just a matter of our opinion . . . [Scripture is] not merely the probable echo of our own feeling and judgment, but objectively the witness of divine revelation and therefore the Word of God as the Word of our Lord and of the Lord of His Church.”

In these sentences, Barth reflects the Reformed fear of projecting human needs and presuppositions upon God, and states that authentic orientation toward God entails setting aside “our own feeling and judgment” to objectively receive revelation, that is, what God reveals about himself which is unknowable by human means without divine assistance.

For sixteenth-century Protestants, any religious fascination with an object as a manner of apprehending the divine is itself an idol—one thinks of Calvin’s antipathy even for mental images—the object in this case fascinates because it reflects back an image of the self. Pursuing faith as an experience for its own sake could be seen as the cause of idolatry. In terms of visual/spiritual perception, the remedy to this dilemma is to learn to really see, to recognize the difference between one’s experience of contemplation and the reality one seeks, in which one is seen and addressed by God.

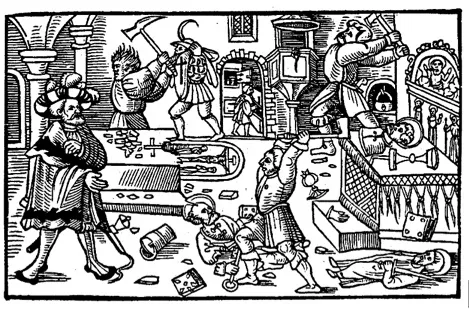

The psychology of visual perception helps us understand why the issue of idolatry was of such elemental importance in the Protestant imagination. If God perceives the human person and speaks for himself, then an experience of worship that is valid refuses to put forth one’s own image for God, which inevitably communicates a false god. For Calvinists, God cannot be portrayed in material form, a contradiction of Isa 40:18 (“With whom, then, will you compare God? To what image will you liken him?”) The iconoclastic instinct, so fiercely and tenaciously held by early modern Reformed Christians, revealed a desire to remove any impediment to a vital relationship with God (see figure 1).

Figure 1: Protestant suspicion of images caused outbreaks of iconoclasm, though in many areas of Switzerland the dismantling of sacred art took place gradually, or in an ordered manner sanctioned by city authorities.

Iconoclasm suggests that its perpetrators did not consider images benign—or nothing at all—but rather found them to be powerful, magical, alluring, and negative. Further, David Morgan argues, following art historian David Freedberg, that no religion is truly “aniconic,” explaining that iconoclasts “need the other to destroy in order to construct a new traditi...