![]()

1

Entering Wingren’s Theological Life

This book deals with Gustaf Wingren (1910–2000), one of the most influential and creative Swedish theologians of the twentieth century. I became acquainted with him around 1980, after he had retired. I had known about Wingren before then, and attended several of his many public lectures during the latter half of the 1970s. At that time in Sweden, Wingren’s name was on the lips of many, and at several of the public events at which he lectured I was given the opportunity to speak to him briefly. It was, however, not until I had left Gothenburg, where I had started my academic studies, and moved to Lund in January 1982 that I embarked on a more personal relationship with him.

My years in Lund came to have far-reaching effects on my worldview. The most important influence on my intellectual development during that period was not, however, the formal academic coursework. The opportunities for informal education and personal cultivation, which were still so much a part of the culture of that city and its university, had a far greater impact on me. I truly enjoyed the way that unexpected learning adventures could occur at almost any time or place in the ancient, spired city of Lund. I knew that I shared this experience with many others, but did not realize that even Wingren had once been overwhelmed by the same dizzying excitement for learning. Fifty-five years earlier, in 1927, at the tender age of sixteen, he had arrived in Lund on the night train one warm summer morning. He would remain there, in what he considered to be the spiritual capital of Sweden, for the rest of his life. As for me, I left after less than five years.

Our Personal Beginnings

I do not remember exactly when it was, but sometime in January 1982, during my first few weeks in Lund, I was invited to the home of Gustaf Wingren and his second wife, Greta Hofsten (1927–96). Over time, their intellectual collaboration developed to such a degree that they were almost inseparable. The professor, who had retired five years earlier, wanted to discuss theology with me. He said it with an eagerness that should have piqued my curiosity about what awaited me, but I was a novice at the time. Nonetheless, I did prepare for our meeting by reading several of his most important works. I rode my bicycle through the cobblestoned streets of central Lund to the high-rise building at Warholms väg 6B, and climbed the narrow staircase to the second floor. Gustaf, in his characteristic knitted sweater, was already waiting at the top of the stairs. The apartment door stood ajar on the left side of the hallway behind him, as it would always be whenever I came to visit during my years in Lund. On this particular occasion, however, I entered a completely new and unknown environment for the first time.

As I entered the apartment, I was struck by the spartan furnishing and sparse decor. To the left of the main hallway were two bedrooms, where the Hofsten-Wingrens each had their own little cubbyhole, furnished in the same way with a narrow single bed, a bedside table, and, I believe, some sort of wardrobe. Greta’s room also contained a small desk. Straight on down the hallway was the living room, where a pair of old beds had been made into a rather uncomfortable sitting area. Apart from that, the room was dominated by two substantial armchairs, both placed with their backs to the balcony windows to make use of the light for reading. On several tables, piles of books lay stacked one upon the other. Later I learned that the books were ordered in a sequence and that the order in which they lay would change according to the couple’s shifting intellectual priorities and how their discussions had progressed. As soon as the books landed on their tables they were quickly devoured by the two voracious readers. It struck me that there was no television in the apartment; that probably guaranteed them the time for so much reading. The gracious warmth with which they received me made me feel welcome at once. However, in this cerebral home there was hardly any time for respite or rest.

Beyond the living room, at the back of the apartment, was another good-sized room, which served as Gustaf’s study and library. His collection of books had been decimated six years earlier in the divorce settlement with his first wife, Signhild. The kitchen was equally as spartan, but blue doors on the cabinets gave some color to the room, and the small table under the window seemed to invite guests to meals and conversation. During my nearly five years in Lund, I partook in numerous lunch and dinner discussions at that little kitchen table. These were never large or elaborate parties. I cannot remember that we were ever more than four people seated around that table, although when I look back at my journals from those years, I realize that there were exceptions. The meal always began with Gustaf saying grace in Latin. The food was simple and in traditional Swedish style, and was washed down with aquavit.

On the day in January 1982 when I was first invited to the Wingren home, I looked forward eagerly to the opportunity to discuss theology with the world-famous theologian. I remember how Gustaf told a number of animated stories to help explain what he meant. In order to follow his reasoning, you had to pay careful attention to the tiny details as well as to the drastic leaps in the string of stories that carried his presentation forward. I can still see the excitement in his eyes and hear the engagement in his voice from this first private meeting. Most of all, I remember the level of energy in our discussion.

As we talked, Gustaf gradually became quite agitated, even furious. For the life of me, I could not understand why my questions, simple objections, and opinions brought out such a remarkable mixture of anger and amusement in him. The longer we spoke, the more our discussion developed into what seemed a magnificent quarrel. Evening fell, the apartment darkened, and finally, our discussion came to an end. Gustaf’s wife, Greta, said a few friendly words to me as I departed, but the entire escapade left me rather crestfallen. I left Warholms väg with the definite feeling that our new friendship had already reached its end.

Several days later, Gustaf telephoned me. To my great surprise, he told me that he was eager to see me again. He sounded enthusiastic. “We must continue our talk,” he declared. He said that he had found our discussion especially refreshing. When could I come back? Perplexed, I stood in my dormitory hallway with the telephone receiver in my hand. Slowly, I began to realize what sort of person I was dealing with. Gustaf Wingren was the sort who found odd enjoyment in confrontation. If there were not yet any burning conflicts in which he could become involved, he would create them on his own. And when the confrontations were over, he wove dramatic stories about them. His rhetoric was peppered with anecdotes that were as entertaining as they were pertinent, and he presented them carefully and painstakingly, one after the other. He seemed to use his stories as critical barbs to provoke and tease, in the hope of luring people into the arena of discourse. His use of narrative and his seeming desire to ridicule were inseparable. Through his fantastic tales about people and ideas in confrontation, Gustaf (and Greta, who after his retirement came to be his most important colleague, although she held no academic position) opened up a vast intellectual world for me—a world that in reality became my most important university during my years in Lund.

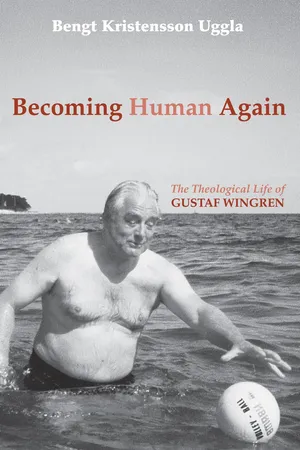

I soon realized that the Gustaf Wingren with whom I had begun to socialize was in many respects a completely different person from the one earlier generations of Lund students and teachers had encountered as a professor, advisor, and colleague. Those who had attended the University in the 1960s always referred to their old teacher simply as “Wingren.” When I met former students who had attended in the decades prior to the 1960s (and who were not much younger than their former advisor; several of them had by then become bishops in the Church of Sweden), they spoke of Professor Wingren. With few exceptions, members of both of these groups looked quite surprised when my contemporaries and I spoke about, and even addressed, their old professor simply as Gustaf. I now understand that I did not fully recognize the profound transformation the professor had undergone, personally as well as theologically. In the mid-1970s he shed his impeccable dark suit and carefully knotted necktie for an outdoor hiking jacket, a knitted sweater, and practical, soft-soled shoes. In this new uniform, he bounded through the city on protest marches and other progressive events, which often had a strong presence of young people. Professor Wingren had undergone a metamorphosis and become Gustaf. This afforded me the opportunity to come into closer contact with him, but at the same time, I believe this also obscured my perception of him, so that I was not really aware of the discontinuities in his life and the complications that were characteristic of his earlier personal history. As a result, I underestimated the importance of the transformation his theology had undergone from the 1970s onward, when he had recontextualized the entirety of his theological system and transformed it into a critique of society. An innovative hermeneutical approach allowed him to recycle the theological sources and concepts that he had developed in an academic context by reconfiguring them according to a social frame of reference. Thus he generated an entire new series of books. This hermeneutical transformation is the focal point of this biography.

How did this happen? What were his personal and intellectual resources that made this transformation possible? The prerequisites for change may have lain dormant as a potential resource and seem to have intensified over a long period of time. T...