![]()

1

Introduction

The Transformational Nature of Missionary Service

Historically missionaries have been transformational agents. In some cases this has drawn a critical response as it is believed that the change they bring is destructive of values that give internal coherence to indigenous cultures. In other cases they are praised for changes that operate as incarnational seeds of healing and hope. Missionaries themselves often speak of another kind of transformation. This is a perceptual alteration that occurs as their encounter with other cultures and faiths allows them to see the world through new eyes. Many would identify this as the most profound change, particularly so when it involves a revolution in their assessment of the religious other.

For missionaries whose conceptualizations represent the more conservative side of the theological spectrum this can be a wrenching experience, as it may mean attributing greater value to a religious identity they had previously anathematized. In some cases this may lead to their questioning the validity of their missional purpose. More often, it engenders a reorientation in a more dialogical direction. This was my experience during the twelve years (1976–1978; 1986–1996) my wife and I spent in cross-cultural ministry in the Arabian Gulf states of Bahrain and Oman. Many others who have shared our experience would agree.

Shifting Missionary Perceptions

The question that has intrigued me for some time about this phenomenon is whether it was also the case for earlier American missionaries. My attempt to discover an answer to that question prompted me to write a paper exploring the ministry of the pioneering Reformed Church in America missionary to the Arabian Gulf, Samuel Zwemer, which appeared in the International Bulletin of Missionary Research in July of 2004. What I discovered in doing research for this paper is that Zwemer did undergo a transformation of sorts in his perception of his Muslim neighbors, allowing a polemically defined categorical approach to evolve into something more appreciative of Muslim humanity, diversity and spirituality. It was a movement from “polemic to a hint of dialogue” in anticipation of later developments in Christian-Muslim relations.

Kenneth Cracknell discovered a similar phenomenon in research he did for a book he published in 1995 with the title Justice, Courtesy and Love: Theologians and Missionaries Encountering World Religions, 1846–1914. Cracknell’s interest was less shifting missionary perceptions of the religious other than the broader issue of the Christian theology of religions. “Within [this book],” he says, “we examine one aspect of missiology: the vital question of the significance of other peoples’ religions within the purposes of God.” But the approach he took to his research put his discoveries within the framework of my own interests, as his work involved examining the evolving perceptions of a collection of nineteenth and early twentieth-century western missionaries and theologians. It is in his description of the difficulties such a study entails that I take inspiration for my own research.

This is the primary concern of what follows; to undertake a “searching analysis of the views and opinions” of an early American missionary prior to his departure for his chosen field of service in order to examine whether or not a personal encounter with the subjects of his missionary interest “altered [his] perceptions and caused major shifts” in his thinking. The focus in this case will be on how he perceived the religious other in the framework of his missiological task.

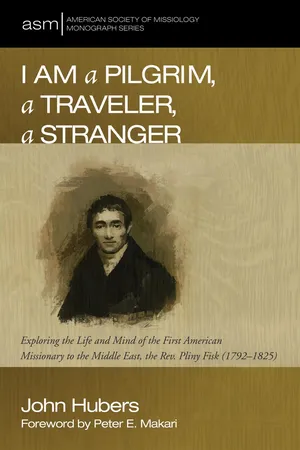

Subject of Inquiry: The Rev. Pliny Fisk

The subject chosen for this study is one of a pair of missionaries sent to the Ottoman Empire in 1819 by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (hereafter ABCFM) with a primary purpose of exploring possibilities for a missionary engagement with the peoples of the Holy Land. His name was Pliny Fisk. His traveling companion was his friend and fellow Andover graduate, Levi Parsons. What makes Fisk a particularly interesting subject for an inquiry of this nature is the fact that he made this trip at a time when only a handful of Protestant missionaries had journeyed to this region, none of them American. His story in this case provides a unique opportunity to examine the transformational nature of a cross-cultural missionary encounter in its pioneering stage.

An Orientalist Model

The model of analysis I have chosen to determine the nature of Fisk’s transformational experience takes its inspiration from Edward Said’s observations about orientalism in the western scholarship of the era. What is most pertinent here is the distinction Said draws between what he calls “vision” and “narrative.”

According to Said, this ‘static system of “synchronic essentialism” that he designates “vision,” is such a fixation of the orientalist discourse that it effectively “defeats” the possibility of a less rigid, more humanizing “narrative,” even when the discourse in question emerges from an existential encounter. This is a primary thesis of his work.

John M. Steadman anticipated Said’s observations in his book The Myth of Asia, published nine years before Orientalism. Steadman noted how there has been a long history of bias in western scholarship towards what he calls “ideation” that creates a unitary vision of the Orient that obfuscates more than it enlightens.

Neither Said nor Steadman had missionary literature as their primary focus of concern. Said, in fact, attributes the orientalist project to “secularizing elements in eighteenth-century European culture” (even while acknowledging that such elements drew...