- 134 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the 1960s, the virtues have been making a comeback in various fields of study. This book offers an overview of the history of virtues from Plato to Nietzsche, discusses the philosophy and psychology of virtues, and analyzes different applications of virtue in epistemology, positive psychology, ethics, and politics.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Virtue by Vainio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Philosophy History & Theory1

What is Virtue?

From the beginning of history and within practically all known cultures, we have observed human behavior in terms of virtue. The various virtue traditions have a lot in common, but they also differ from each other. Philosophers and scholars have even severely criticized each other’s theories of virtue. In this chapter we will look at definitions of virtues, their history, and key themes in current debate, such as whether it is really possible to be virtuous.

A general definition of virtue

Virtue typically refers to a character trait that expresses some sort of excellence.1 This is what is meant by the Greek concept arete. Generally, the crucial feature of virtue is that it is a mean between two extremes, lack and excess. For example, a person is brave when she behaves neither cowardly nor foolhardily. Finding the mean is often very hard, and this ability, which Aristotle calls practical wisdom (phronesis) is learned through experience alone.

What has been said is confirmed by the fact that, while young men become geometricians and mathematicians and wise in matters like these, it is thought that a young man of practical wisdom cannot be found. The cause is that such wisdom is concerned not only with universals but with particulars, which become familiar from experience, but a young man has no experience, for it is length of time that gives experience; indeed one might ask this question too, why a boy may become a mathematician, but not a philosopher or a physicist. It is because the objects of mathematics exist by abstraction, while the first principles of these other subjects come from experience, and because young men have no conviction about the latter but merely use the proper language, while the essence of mathematical objects is plain enough to them. . . That practical wisdom is not scientific knowledge is evident.2

Even a very young child may have an extraordinary, completely unaided and natural talent to add and subtract numbers but she is not as skillful in, for example, settling quarrels and avoiding them. It is easy to see the difference between, on the one hand, wisdom and virtue and, on the other hand, scientific knowledge and skills. A person can, at the same time, be highly intelligent but stupid, or even evil.

To give one enlightening yet gruesome example: If you visit the concentration camp at Dachau, just a few miles north of Munich, you can see an exhibition that portrays the methods of medical doctors before and during the Nazi regime. The doctors used political prisoners and other enemies of the state to test how long humans can survive in freezing water, and the method consisted of freezing people to death in large vats. Of course, the data that they retrieved was valid and even scientifically beneficial. The doctors were not dumb but they were evil, and their high intelligence did not help them to avoid the moral horrors they committed. Succeeding in that would have required virtues, which they did not have to a sufficient degree.

Practical wisdom differs from all other virtues in that it does not itself have a mean. You can never get too good at finding the mean between the extremes; one cannot become too wise. Wisdom can grow without limit because wisdom means the ability to apply rules and principles in differing situations. Other virtues always involve right proportion. A generous person is not too generous (so that he gives away all his belongings) but knows how to balance his benevolence. Failing in generosity results from too narrow a view. A person who is too generous is not temperate and just. This is called the unity of virtues: succeeding in one virtue is dependent on succeeding in others. Virtues cannot be isolated from each other, and a practically wise person is one who knows how to balance all the relevant virtues in varying contexts.

Virtues in different traditions

In ancient Greco-Roman philosophy, the four cardinal virtues were temperance, courage, justice, and wisdom. The name “cardinal” comes from the Latin word for hinges (cardines); all the other virtues are dependent on these virtues as hinges hold a door in its place. Drawing on 1 Cor 13:13, the medieval Christian tradition adds three theological virtues to these: faith, hope, and love. This is still perhaps the most well-known way of listing virtues in our time. However, virtues are not something that only European or Christian philosophy recognizes. Other religions and philosophical traditions contain their own virtue theories and lists.

In Buddhism, the Noble Eightfold Path is one of the basic principles of ethical deliberation. To those who follow it, the path offers redemption from suffering through growth in wisdom. Central to this process is the concept of samyañc, which can be translated as right, complete, coherent, and whole. The virtues listed in the Path are: right view of life, right intention, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration.

The Veda texts and Upanishads of Hinduism mention courage, forgiveness, temperance, freedom from lust, purity, deliberation, truthfulness, and freedom from anger as principal virtues. Other important ethical virtues are the principle of non-violence (ahimsa) and self-control, which are also underlined in Buddhist traditions.

Islam considers the prophet Muhammad as the incarnation of virtue and his pieces of advice (hadith) are the ground for ethical thought and conduct. Islamic theology has produced lists of virtues that are not that different from the traditions mentioned already. A special feature, however, is the emphasis on the virtue of obedience and fasting as the exercise that trains the person to live a life of self-control.

In the Old Testament, Proverbs contains several verses where virtues are presented through familiar images. For example, Proverbs 6:6 urges the reader, “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider its ways and be wise!” The rabbinic tradition develops virtue theory so that peace and harmony (shalom) becomes the aim toward which Torah is directed.

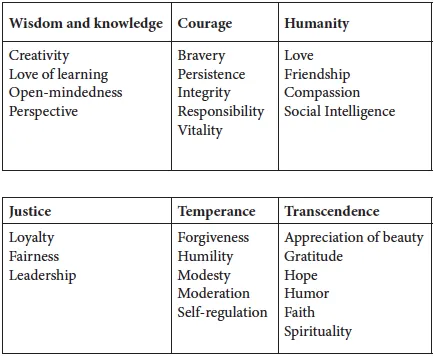

Contemporary psychologists, especially those working in the tradition of so-called positive psychology, have been interested in virtues as they are understood in different cultures. Christopher Peterson and Martin Seligman argue that, even if there are differences in emphasis between cultures, the virtues fall nicely into six classes that can then be divided further into classes.3 The list and taxonomy is not supposed to remain absolute but is more like a heuristic tool that helps us to get a grasp of virtues as a whole.

It is customary to draw a distinction between moral and intellectual virtues. Intellectual virtues include, for example, open-mindedness, carefulness, honesty, intellectual courage, independence, and perseverance. However, it is not always possible to make a clear distinction between moral and intellectual virtues because some intellectual virtues require moral uprightness and vice versa.

Habituation and virtue

The ancient Greeks used the word “virtue” to denote all kinds of practical skills, like running and spear throwing. These skills were acquired through practice so that they were almost automatic and effortless. For example, a person who is a fast runner does not need to put in a lot of effort to run 100 meters in less than 15 seconds, whereas someone who has not practiced as much will be half dead after the run and with well over 20 seconds on the timer.

Soon the terminology starts to develop and become more precise, and skills and virtues are separated, while it is still held that both of these require practice and they can both become automatic and effortless. However, we do not consider a person who knows how to tie a bowtie virtuous; he is merely skillful. In order to pass as virtuous, one needs to have a larger set of both practical and theoretical character traits. Moreover, virtues require the ability to apply the knowledge in constantly changing environments in a coherent manner. It is not enough to know the rules of proper behavior but one needs to know how to employ them.

The practice of virtues is called habituation (from Latin habitus). Habitus is what enables a person to act in ways that are excellent. Sometimes habitus is called “the second nature,” which underlines the automatic aspect of virtuous behavior. If someone possesses a virtuous habit, she will perform her actions effortlessly, immediately, and feels joy in doing so.

Virtuous action is related to a person’s character through her temperament and acquired habits. Temperament means that part of your personality that is very hard to modify or change. For example, someone may be naturally gentle and therefore it is easy for her to be temperate and it is difficult to aggravate her, no matter how hard she is provoked. Acquired habits are easier to change. For example, let us think of a judge who has given verdicts in the past that he now, through greater experience and knowledge, considers to be unjust. This process of learning changes his habitus and remodels his actions so that he now makes just decisions. The first actual decision may be hard to make but making choices gets easier little by little.

According to traditional virtue theories, virtuous action can be brought about through four different routes. First, we can be naturally inclined toward certain virtuous behavioral patterns. Second, through repetition we can gain the ability to perform virtuous and moral actions. Third, we can practice rational deliberation so that we ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1: What is Virtue?

- Chapter 2: The History of Virtues

- Chapter 3: Virtues and Vices

- Chapter 4: Applications of Virtues

- Final Words

- Bibliography