- 140 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

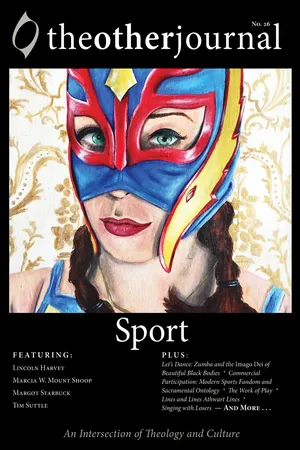

The Other Journal: Sport

About this book

FEATURING: Adam Joyce, Lincoln Harvey, Marcia W. Mount Shoop, Margot Starbuck, and Tim SuttlePLUS:Let's Dance: Zumba and the Imago Dei of Beautiful Black Bodies * Commercial Participation: Modern Sports Fandom and Sacramental Ontology * The Work of Play * Lines and Lines Athwart Lines * Singing with Losers --AND MORE...The ancient Olympic games were held every four years at the temple of Zeus. They were a major cultural and religious event that doubled as a contest between rivaling nation-states. Certain strands of mythology even suggest that Heracles, the strongest of mortal men, organized the event and built the Olympic stadium in honor of his father, Zeus. Today, few athletes devote their efforts to the honor of Zeus, but there remains a certain religiosity at work in sport's place within Western culture. Fame, fortune, and honor; character and fair play; skill and artistic perfection also remain at stake, just in new ways. As Marcia W. Mount Shoop explains in her interview with Jessica Coblentz, sports still "tap into our most primal existential needs for vitality, for purpose, for creativity, for connection and community, and for work and play," and in this, our twenty-fifth issue of The Other Journal, we dive into these characteristics of sport, starting literally with Jennifer Stewart Fueston's poem "A Swim" and then continuing on to the ancient Greek stadium at Nemea. Our contributors consider the ethics, commodification, and embodiment of particular events, as well as the personal and cultural stories which weave in and out of sport. They do the hard work of conscientious fandom at football games; walk us through baseball liturgies; and take us to the windy courts of Philo, Illinois, where noted author David Foster Wallace was an outdoor tennis savant. They show us how to fly and then how to lose. And they invite us to dance, "to let our bodies taste the salt of our sweat, hear the pant of exhalation, and feel the perspiration on our skin, for it is in these very possibilities," argues John B. White, "that we relate to God, others, and self."The issue features essays and reviews by Jeff Appel, Andrew Arndt, Ben Bishop, Jen Grabarczyk-Turner, Lincoln Harvey, Jonathan Hiskes, Adam Joyce, Lakisha R. Lockhart-Rusch, Benj Petroelje, Justin Randall Phillips, Heather L. Reid, Margot Starbuck, Tim Suttle, and John B. White; an interview by Jessica Coblentz with Marcia W. Mount Shoop; creative nonfiction by Brett Beasley, Meghan Florian, and Katie Karnehm-Esh; poetry by Bethany Bowman, Catherine Thiel Lee, and Jennifer Stewart Fueston; and art by Allen Forrest, Gerald Lopez, and Abigail Platter.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1 A Swim

2 The Training of the Olympian Soul

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Letter from the Editors

- 1 A Swim

- 2 The Training of the Olympian Soul

- 3 Holy Play: Toward a Christian Engagement with Physical Fitness

- 4 Hunger

- 5 Let’s Dance: Zumba and the Imago Dei of Beautiful Black Bodies

- 6 The Redemptive and Demonic in Big-Time Sports: An Interview with Marcia W. Mount Shoop

- 7 La Pasión del Luchador y el artista Gerald Lopez

- 8 Commercial Participation: Modern Sports Fandom and Sacramental Ontology

- 9 We’re Number One: Sport as the Liturgy of Empire

- 10 How Does a Sacrificial Moral Ethic Help Parents Navigate Youth Sports?

- 11 Raising an American Boy in a Division-One Town

- 12 You Always Begin an Essay (or a Theology) in the Middle: A Review of Stanley Hauerwas’s The Work of Theology

- 13 Runners and Losers

- 14 Lines and Lines Athwart Lines: Givenness, Limits, and the Practice of Sport

- 15 Jesus Christ and the Rules of the Game

- 16 Fitness Centers and Health Clubs: Missing the Mark?

- 17 Peacock

- 18 Every Year Is Our Year

- 19 The Work of Play

- 20 Singing with Losers

- 21 Wrestler

- Contributors