- 146 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The growth and religious commitment of the Latino community in the U.S. presents a unique set of challenges for pastors in that community. Walk with the People: Latino Ministry in the United States identifies and analyzes the contemporary challenges facing Latino churches in the U.S. and some of the issues they are likely to face in the future. Latino pastors and others working in the community need to understand and grapple with these challenges. As the Latino community continues to grow and diversify, effective church leaders in Latino congregations will need to retool their ministries to address these changes.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Walk with the People by Juan Francisco Martinez in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Ministry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Complexities of our Latina Reality

On Plaza Olvera in Los Angeles one can buy tee shorts that say things like “I am Chicano, not Hispanic.” One the other hand, a friend that recently arrived in the United States was lamenting: “I have been an Argentinean all my life. Now I am in the United States and they tell me I am Latino. I have never been Latino and I really do not understand what that is.” These two examples reflect the complexity of Latino identity. We utilize terms like Latino or Hispanic to describe ourselves and some of us insist on one or the other. There are also many among us that reject either of the two terms and do not understand why we are identified as Latinos or Hispanics and not by terms that identify our specific national backgrounds.

The United States Census and government offices began using the term Hispanic to identify the “Hispanic” peoples in 1970. Since that date it began to be used as a category next to the “racial” categories of white, Asian-American, African-American and other similar categories. Hispanic is neither a racial, ethnic, national, geographic, nor linguistic category, though it includes aspects of each of these. Therefore, the Census uses a series of explanations next to the term to clarify what it means and what it does not mean and who is or is not Hispanic.

The community has debated the usage of Hispanic and many have preferred the term Latino. Many reasons are given for the preference, including that Hispanic identifies the community with Spain, while Latino identifies us with Latin America. There have also been political and regional debates with respect to each word used to identify Latinos in the United States. It is a debate that reflects the complexity of the people that one wants to identify with the terms.4

Both Latino and Hispanic are terms that define the unity of various US communities that have ties to Latin America or with the Spanish speaking world. They serve as a type of umbrella that focus on what unites us, but they also mask a whole series of differences between those called Latinos. Ministry among Latinos is done in the space between the unity and the multiple differences among our people.5

Our Identities

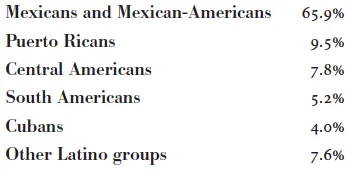

There are many types of national, ethnic, racial, and cultural distinctives among Latinos. One of the common ways to define those differences is by means of our national backgrounds. According to the US Census Latinos have the following national backgrounds:

This way of describing our differences places the emphasis on our histories and on the national and cultural influences that formed us. If we describe Latinas this way we notice several geographic and demographic tendencies among Latinos. For example, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans are concentrated in the Southwest, Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in the Northeast and Cubans in southern Florida.7 Defining ourselves by our national backgrounds helps us identify how and when we became a part of the United States and to recognize the cultural differences that formed us.8

This type of distinction takes our national backgrounds into account, but hides the differences within those backgrounds. Many “minorities” within the Latina minority become invisible in this description. In particular, indigenous immigrants, those of African descent, those from English or French speaking areas, those who come from immigrant communities that have maintained there previous national identities, or those that were recent immigrants to Latin America before coming to the United States.

This is a point that those of us who were born outside of the United States need to be helped to understand the million of historical factors that affect our ministries: how people feel and react when they confront specific people or situations. What is more, it is not the same to have been born in Mexico (very close to the US) than haven been born in Argentina (very far).—Jorge Sánchez

Defining ourselves by our national backgrounds is also not useful when describing our place in the United States today. It gives the impression that all Latinas are immigrants, people who recently arrived from “outside.” It does not take into account that the first European communities in what is now the United States, were Spanish, not English, and that there has been “Hispanic” influence in the territorial US for centuries. This framing does not take into account the Latinos in the United States who are descendents of those who arrived in what is now the United States when it was part of Spain or Mexico. It also does not take into account the particular reality of the Puerto Ricans who have been citizens of the United States almost since this country conquered the island from Spain more than a century ago, but who, nonetheless, live in an “intermediate” situation since Puerto Rico is neither an independent country, nor a state of United States. These histories of “conquest” point toward another way of reflecting on the differences between us, the differences between our experiences with relationship to the United States.9

Those who were in the Southwest when the United States took the land from Mexico were conquered. Puerto Ricans were colonized after the United States took the island from Spain. On the other hand, Cubans have usually been accepted as political refugees, so they have had a much more positive experience in the United States. The experience of other immigrants has varied, many times depending on educational background and the color of one’s skin. Usually the person that arrived in the United States with a visa has a very different perspective than the one that arrived as an undocumented alien. There also tends to be a different experience for those with a European background as opposed to those with African, Asian, indigenous, or mestizo backgrounds. That is why many Latinas see this country as a land of great opportunity and acceptance while others have more negative or ambivalent perspectives. This does not take into account the complexity of the undocumented who come to this country hoping for new opportunities, but who live in the shadows of US reality and in fear of legal officials.

There is still another very important factor that defines us and makes our differences stand out. This has to do with the level of identification with Latino culture and the level of adaptation and assimilation to majority culture in this country or the level of encounter with other minority groups. At this point we are talking about each Latina’s self-identity, how are we a part of the Latino reality in this country and how are we a part of the larger society? This factor recognizes that we are a people in process. One cannot describe Latinos statically or mono-culturally (Latino or Anglo). This factor recognizes that Latinos are a people in cultural and social movement and that many of us have polycentric identities.10

The following diagram can help us understand the complexity of our identities:11

Diagram #1 Levels of Identification with Latino Culture

This diagram demonstrates that there are many things at play when we think of our Latino identity. We live under the influence of majority culture and its assimilationist tendencies. There are many things that pull us toward majority culture, including the mass media, the public schools, and direct and indirect social pressure. We also recognize that everyone who lives in the United States has to adapt to majority culture at some level, even though the person might look for ways to maintain a particular ethnic identity or might live in areas with a high concentration of Latinos.

On the other hand, there are also other cultures in this country. Even though they do not have the same power of attraction as majority culture, some, in particular the African-American culture, have had a great deal of influence on US Latino culture. Some Latinos have also been drawn by some of the other cultural expressions one finds in this country.

There are also some factors that strengthen Latina culture, such as history, migration, Spanish mass media, and the size of the community. But we recognize that Latino identity is polycentric and fluid. There seems to be some movement in which Latinas can opt for the level of identification they want to have with their background. Within this movement and these influences we can identify various types of levels of identification with Latino culture and with majority culture.

In the first place one finds nuclear Latinos. These are people that live almost completely with their Latino community and have very limited contact with majority culture. Many times these people are recent immigrants or people that migrated when they were older adults. The majority of these people speak Spanish as their principal or only language.

Generally one assumes that nuclear Latinos are recent immigrants from Latin America that only speak Spanish and live in Latino barrios. But there is also a significant group of Latinos who fit in this category even though they speak little Spanish or only speak English. These are people who live in areas of high Latino population density (such as south Texas, northern New Mexico, the agricultural communities of central California or parts of Los Angeles, New York, Miami, or Chicago) and who were raised and live their lives in Latino communities. Their culture is not Latin American, but it is also not “Anglo.” These communities reflect cultural adaptation to US society, but they also maintain strong distinctive Latino traits and many are strengthened by new immigrants.

The second type is a bi-cultural Latino. This person lives his life negotiating between majority culture and the Latino community. He understands the cultural “rules” of each group and can fit in either. He chooses to maintain a balance between both in his being, almost always with some level of tension. The majority of these people were born or raised in the United States. Generally they are fully bilingual and can speak both languages without an “accent.” They live different aspects of their lives in each of the two worlds, though sometimes they do not fully feel comfortable in either.

There are also bi-cultural Latinas that learn to live between Latino culture and another minority culture. What was said in the previous paragraph applies to them, but in relationship to another minority group in this country.

A third type is the marginal Latino. This person has not disconnected herself from Latino culture, but she only identifies with it in an occasional manner. She likes some of the Latino cultural artifacts (food, music, soap operas, etc.) and enjoys spending time in the Latino community, but she lives her live according to the patterns of ma...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- People Interviewed for the Book

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Complexities of our Latina Reality

- Chapter 2: Protestants and Latinos in the United States

- Chapter 3: Resources within the Latino Community and Church

- Chapter 4: What Latino Churches are Doing

- Chapter 5: Ministering for Today and for Tomorrow

- Chapter 6: Dreams and Visions

- Resources for Latino Ministry

- Endnotes